On Propaganda And Memory

The Gold of Austria, the Communists of Cambodia, the Hindu Revivalists of India, and Mani Ratnam

I asked the ochre-clad godman of the ashram I am living in currently, near Madurai, about where he stands on the Tamil-Sanskrit debate. I call him swamiji, because my parents under his hire and influence ask me to call him that; and he is kind to me and my parents, and though I don’t understand his allure, I don’t understand much about my parents so I let this slide. They remind me of this wonderful quote from RK Narayan’s The Bachelor Of Arts

It never occurred to them to doubt. They were innocent and unsophisticated in most matters (except their fractions and fights), and took an ascetic make-up at its face value.

Since swamiji speaks both Tamil and Sanskrit fluently, lectures in the former, prays mostly in the latter, I thought he must have an opinion on Dravidian revivalism, and how it sees Sanskrit and Sanskrit-based languages like Hindi as an imposition; the hegemony of the Indo-Aryan languages.

He told me in Tamil that this division is entirely a creation of the left-wing media, that his prayers weave between Tamil and Sanskrit, though it is mostly the latter, and he sees no issue in embracing both. Just that morning I was talking to Devdutt Pattanaik and he told me how in local temples Sanskrit verses are mostly replaced with those in the local languages. Swamiji’s view was that this is propaganda. (I wanted to ask about his memories of the Dravidian movement, of Karunanidhi’s film dialogues, the fight against the imposition of Hindi, the creation of a Tamil heartland, the memories of funds not being allocated to disasters in the South, but I withheld as the prayer ceremony droned on. He sees an agenda at work, and like most people including myself who have bought into agendas, it’s hard to re-wire.)

Propaganda. There again. That word.

I keep stumbling on it- much art, much literature today is described as such, sometimes incorrectly, sometimes innocently, sometimes incoherently.

A book outlining “the untold story” of the Delhi Riots by two Delhi University professors and a Supreme Court advocate was recently withdrawn by Bloomsbury India on the day of its launch. Not because of the editorial standards (which if one goes by the excerpts put out by the author, didn’t seem to exist, with un-cited claims of a ‘Left-Jihadi model of revolution’) but because on the day of its launch, they held an event without the approval of the publishing house, and invited a film-maker who makes propaganda, an editor of a website that peddles in propaganda, and an incendiary politician whose propaganda had sparked the violence that led to the very Delhi riots the book is about. William Dalrymple among other influential writers published by Bloomsbury India took this up, and now we have myriad think-pieces, mistaking freedom to protest, and demanding accountability as the liberal sledgehammer on freedom of speech, to sift through.

Curiously, Mani Ratnam’s films Bombay, Roja, Dil Se, Kannathil Muthamittal etc. recently have been seen as veiled, even worse than propaganda. (Which, while an understandable claim, is philosophically daft, and I’ll come to this in a bit.) This all comes in the midst of political films, films being made by political filmmakers and actors, and the glorification of the state and its instruments in films. It’s everywhere.

I was re-visiting a paper I wrote about propaganda, “How did I lose myself in the Marxist Proletariat dictatorship?” about the violence of the Khmer Rouge in Cambodia between 1975-1979 where 1.5-3 million people lost their lives to hard-labour, untreated disease, starvation, execution, and ‘disappearances’.

Propaganda predisposes itself to the creation of a society that is intellectually homogenous. The intellectual homogeneity consists of a shared goal, a shared rationale of the goal, a shared understanding of the mechanism of achieving the said goal, and most importantly, a shared antagonist.

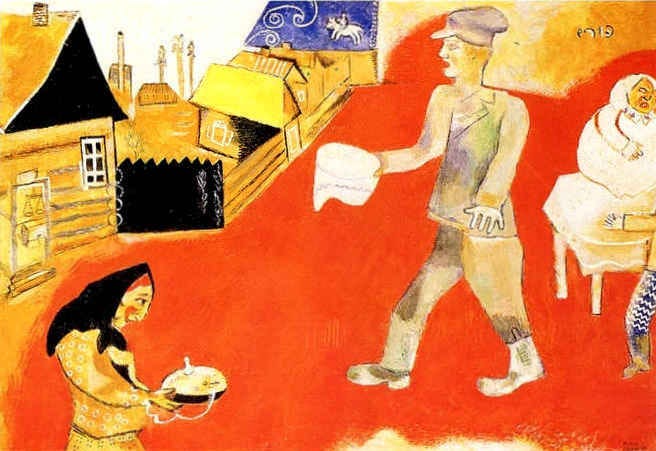

I am thinking of Chagall’s Purin (under). Chagall, a jew (the shared antagonist) had his painting under Hitler’s category of "Degenerate Art" (Entartete Kunst). The painting itself which opened in Munich in 1937 had graffiti and quotations from Hitler’s speeches around it. It was considered degenerate (a shared understanding of the mechanism of achieving the goal- the holocaust), but also got 36,000 people to come on one Sunday alone. (Reminds me of trolls disliking a film’s trailer to create a record of most dislikes, but also creating a record of high views) This idea of degenerate art was existent from the beginning of the 20th century when art critic Adolf Loos in his Ornament and Crime wrote, “Evolution of culture is synonymous with the removal of ornament.” He was against the Secessionists, which included my favourite painter Gustav Klimt. Ornament (Klimt used abundant gold leaf in his paintings) was seen as not just bad art by these puritans, but also immoral. An aesthetic act now became an ethical one. Chagall’s bold abstract painting did little to alleviate their anxieties.

Violence takes many forms and has many reasons. The Cambodian Communist regime of the 70s, that violently moved entire populations of urban citizens into countryside farms to make them work, (Here, it wasn’t racially motivated, but ideologically motivated propaganda, and you can see how this makes creating a ‘common enemy’ difficult) murdering academics (identified as those wearing spectacles), creating a “Year 0”, doing away entirely with private property and currency, forced institutional marriages and uniforms, came out of a severe version of the ‘post-colonial politics of resentment’.

This is true of all propaganda- what we see is the anger and hatred, what we don’t see, but what is always present is the resentment. The question to be asked to someone spouting propaganda thus, should never be what are you fighting for, but what are you resenting? It gives a better picture of the insecurity that is immune to both reason and wrath.

And where there is resentment, memory becomes important. How we remember, and how we are made to remember our past, and how popular art like cinema rephrases that. I had stumbled upon architect and poet Muntansir Dalvi who launched his poetry book online yesterday. I was intrigued by him and found myself listening to a wonderful talk he gave last year on the changing cartography of Mumbai/Bombay citing oft-spoken of figures like GB Mhatre and less-spoken of figures in architecture like Chandrakant Patel. He found memory a pungent origin for much of ideology.

It begins with nostalgia of the past, but as you grow you tend to see that the space around you is constantly shifting, and those things that gave you rootedness or memory are being uprooted, in a way that leave you untethered. We have to find ways to deal with this…

I started architecture school in the early 1980s. It was a time of resolute modernism; you never looked back to the past. History was considered something you wouldn’t refer to because you dealt with what is current, new technology, new material, new necessities of time. The modernism we learned to design was the only thing!”

Dalvi spoke of architecture, (that refused memory, and was thus immune to resentment, and perhaps later, propaganda), as a meta discipline, following in the footsteps of architect Renzo Piano who said, “Architecture is art contaminated by life.” It is a reaction to the now.

You would never design architecture as ars gratia gratis. There is no such thing as art for arts sake; architecture is always related with its context, its habitation, its location, even its time.

So if you ask him why corner building facades in yesteryear Bombay were curved, he will say it is about the cars, the new invention and how this curve helps them make a turns, “Well mannered architecture”. It’s wonderful to think that an artform present to the now is somehow immune to the violence of propaganda. If you are, as an artist, more interested in the present conditions, of labour, of faith, of poverty, of governance, it shows.

Now to end with my hot-take on the Mani Ratnam hot-take. I love his cinema, not because of its politics, but because of its aesthetics, and its economic, biting dialogue. I am not alone in this. Rare is someone who comes to a Ratnam film for a sermon, for they are the least engaging parts of his narrative. There’s a reason he always works with cinematographers who warp and weft images diligently, musicians and lyricists who bring in eroticism and melody, and editors whose chip-chop is entrenched in visual grammar. For him, stories are not an excuse to talk about politics, but politics are an excuse to talk about films. The politics in his films is thus never central, it is the human story- whatever that is- that comes out of it that is spot-lit. So he isn’t a political film-maker, but in whose films politics is incidental, a necessary background. Dil Se was never about the man’s search for truth, because that story track is so shoddy and rushed, it couldn’t have been the central conceit. So now the question arises of whether a non-political (not apolitical) film-maker can make propaganda, (because they are neither fixated on the Now or the Then, they are merely content with their imagination) or like what the writer does in his piece, reduce his body of work to its politics, and then comment on it. Of course the comments on erasure of caste, and the lack of a nuanced take on patriotism is fair, and I agree. But the piece just comes across as a laundry list of moments in his films when the politics was off, without noting that in none of these films was the politics ever the point.

Like the Vienna Secessionists would say, and as is embedded on the entrance to their Secession Building in Vienna, "To every age its art. To art its freedom." And to every freedom perhaps, some responsibility.