On Double Meanings And Movie Reviews

Sometimes while writing reviews I feel like a dermatologist at a birthday party.

My mother found out that the middle-finger is a gesture that reads “fuck-you” when I flipped my brother off in a cab-ride to the airport; she was sitting between us. I was eight years old. Definitely not older. My brother tattled, telling mum what the middle-finger actually means (The Eff Word), and she confronted me in anger, and per usual I remained silent, simmering in my own anger. I don’t know what I was angry about but given that it was about my brother, I am sure I was justified. Now additionally I felt betrayed, I could no longer use the middle-finger to covertly express all the fuck-yous I had bubbling inside me. (It was such a seductive word, perhaps because of its forbidden nature. I remember writing it two dozen times on a white-board I had for practicing rote-learned calculus; a gangster in my teddy bear powder blue pajamas.) The point being that when double-meaning or covert gestures are outed, they lose their purpose. The point of the middle-finger, for me, was not a supplement to a fuck you- it was its replacement. To use it around unsuspecting people, and feel the catharsis of the word.

But there’s also something more, well, profound about double-meaning. I just finished a brilliant book, George Chauncey’s Gay New York: Gender, Urban Culture, and the Making of the Gay Male World 1890-1940. The book is a reply to those who say the gay movement or gay visibility was a post-Stonewall phenomenon. (Below is The Gay Deceiver, a 1939 image by Weegee of a man walking out in drag for one of the infamous drag-balls of New York. This was how visible the community was, albeit policed and violated.) Chauncey argues that gay-culture always existed, we just weren’t looking for it. One of the ways of furtive existence was double-meaning.

The word ‘gay’ itself didn’t have the connotation it does today, it was used in common parlance meaning joyous. But said in the early 1900s with a lilt in the eye and it could mean exactly what we think today. The gays knew this lilt. Anyone asking for ‘a gay place in New York to spend time in’ would not provoke suspicion, but it was the eyes, it’s always the eyes that gave it away.

Asking for matchboxes or the time was another ploy. You might think the man is just asking to have his cigarette burnt, but in reality, something else was burning. Many of these men were living parallel lives with wife and kids, “Double entendre made double life possible.” Cruising for sex was another act that required the vocabulary of double-meaning. When 14th Street was used in a dialogue in a 1930 film, it felt innocuous to those unaware of it being a place where the queers collect, along vaseline alley.

I remember when I was at a sex-shop in Castro I was so intrigued by all the implicit messaging. The shop was empty and so I made the store owner explain to me what every object displayed meant. (He was explaining how a screw driver worked on a prostate and looked back at me squirming, my legs crossed in Garudasana) He came to a row of handkerchiefs each in different colours and prints. He told me each one signified a very specific kink, from fisting, to bondage, to leashes. Wearing a certain handkerchief overtly signified that you were looking for a participant in a very specific act. Chauncey talks about how red ties were used by gay men to identify each other. Of course this doesn’t mean that every guy wearing a red tie was looking for gay sex, but it certainly narrowed down the pool. I keep wondering what these double-meaning mean, today, in a world where

a) the meaning, literal and intended, is exposed through diffused media- you didn’t need to wear a certain coloured handkerchief; you just put your preference on your Grindr profile.

b) the need for double-entendre doesn’t exist apart from in humour. It’s no longer essential. Of course the public space still exists for soliciting; a powerful gaze in a Mumbai local is almost always followed by meanderings and fleeting touches, then grasps. But this isn’t the only and certainly not the most predominant way to meet people.

Double entendre helped equip a generation of men looking for other men. But when today, an app does the same thing, what remains of its potency?

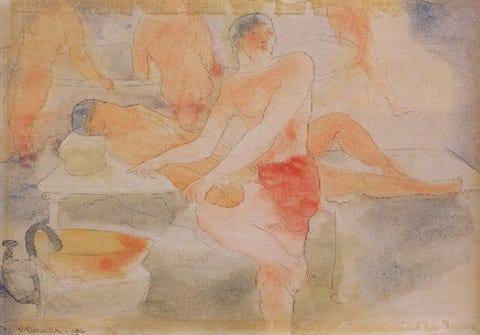

Look at Charles Demuth’s 1916 painting Turkish Baths below where the gays congregated. It began as a space built for public hygiene for the poor, and for socializing for the rich, and it was co-opted into a space for gay-men to pursue lust under the thick fog and hot vapour. In the early 1900s saying you’re going to a bath provokes not much of a reaction; it was mundane. Today, the connotation is very specific.

The very opposite problem is found in metaphors, arguably the worst figure of speech.(Favourite figure of speech has to be alliteration- the fun in phrasing familiar sounds side-by-side is simply supreme!)

While double-meaning is a recognition of what was once integral and indispensable, like how museums are a recognition of what was once integral and indispensable, a metaphor is like those pretentious little tags in those museums, trying to explain what was once lived, reducing it to your own understanding in your own world. Metaphors make cerebral what is meant to be visceral.

I read books or essays with winding metaphors and think, “This is all so constructed, so unlike the mishmash thoughts, or the thoughtless-ness that living a life actually is.” I find it hard to take seriously someone who takes their metaphors seriously.

Sometimes I feel we write about what we watch or read, in reviews, because we are afraid that the process of watching or reading isn’t really an intellectual one. We are forcing it to be that. I say ‘we’ because I owe money to peddling my opinions as a reviewer. But sometimes, most of the times actually, I just feel like a dermatologist at a birthday party. (A phrase I got from here and fully intend to use all the time)

But then again that is what criticism as a genre has always been. I remember thinking after watching a convoluted film like Trance “I can’t wait to read Baddy’s (Baradwaj Rangan) review to figure out what this film meant.”

But you see the problem with that statement is an assumption that art is meant to be cautious, conscious and articulate in its impact- it just can’t wash over you. This is why people hate poetry, an art form that at its best requires you to let go of this need to control meaning while reading.

I am listening to an audiobook of Shuggie Bain, but the narrator has this thick Irish accent that sometimes makes it hard to understand anything. There are minutes where I am just listening to sounds without really knowing much more than the tone of the character. It’s such a different experience, I don’t know if it’s better than fixating on words while reading, armed with a peppy-pink-pen (alliteration!) because there’s really no way to rank my exasperation and exhilaration. It’s like my music teacher scolding me, “Prathyush you’re not feeling anything when you sing,” and I have to tell him, “But sir, what if I get the notes wrong?” I keep telling myself that the feeling will come later, as an additional layer over the structural coherence of Raag Bhoopali. I’m wrong, I know it, but am relentless in pursuing my wrongness. Then there is the movies, where I am not a producer, but a consumer.

The movie-watching experience, for me, has never been heightened by knowing the subtext. When I walked out of the theater after Pain And Glory I texted my editor, who suggested the film, how much I loved it and how I can’t wait to write about it. But really, when I wrote about it, the experience I was describing was very different from that numb ecstasy I felt in the dark theater. Deconstructing meaning and metaphors, the aftermath of experiencing art, is an act of intellectual masturbation. It’s never procreative. But gosh does it feel good.

Then there’s one more thing which I always find funny- Movie reviews use words to write about a visual form. It’s like describing the taste of idli as “fluffy and salty and tasteless”, but a person needs to have eaten the idly to understand the saltiness of an idly is different from that of pickle, and the tastelessness of it, different from that of water. How do you invoke that in words? Maybe this is why I love watching video reviews, it feels more true to the act of watching a movie. But the fucking contradiction in this is that I only write reviews, and that’s how I want it to be.

The last paragraph of Knaussgaard’s 233 page book So Much Longing In So Little Space expresses this conflict incisively, albeit with a different art from- fine art:

In themselves, pictures are beyond words, beyond concepts, beyond thought, they invoke the presence of the world on the world’s terms, which also means that everything that has been thought and written in this book stops being valid the moment your gaze meets the canvas

If you like what you read, tell others. If you don’t, tell me.