On 1970s Bombay Cinema; A Long Read

The Angry Young Man and the Thinking Woman, between parallel cinema and the thudding success of a mythological drama.

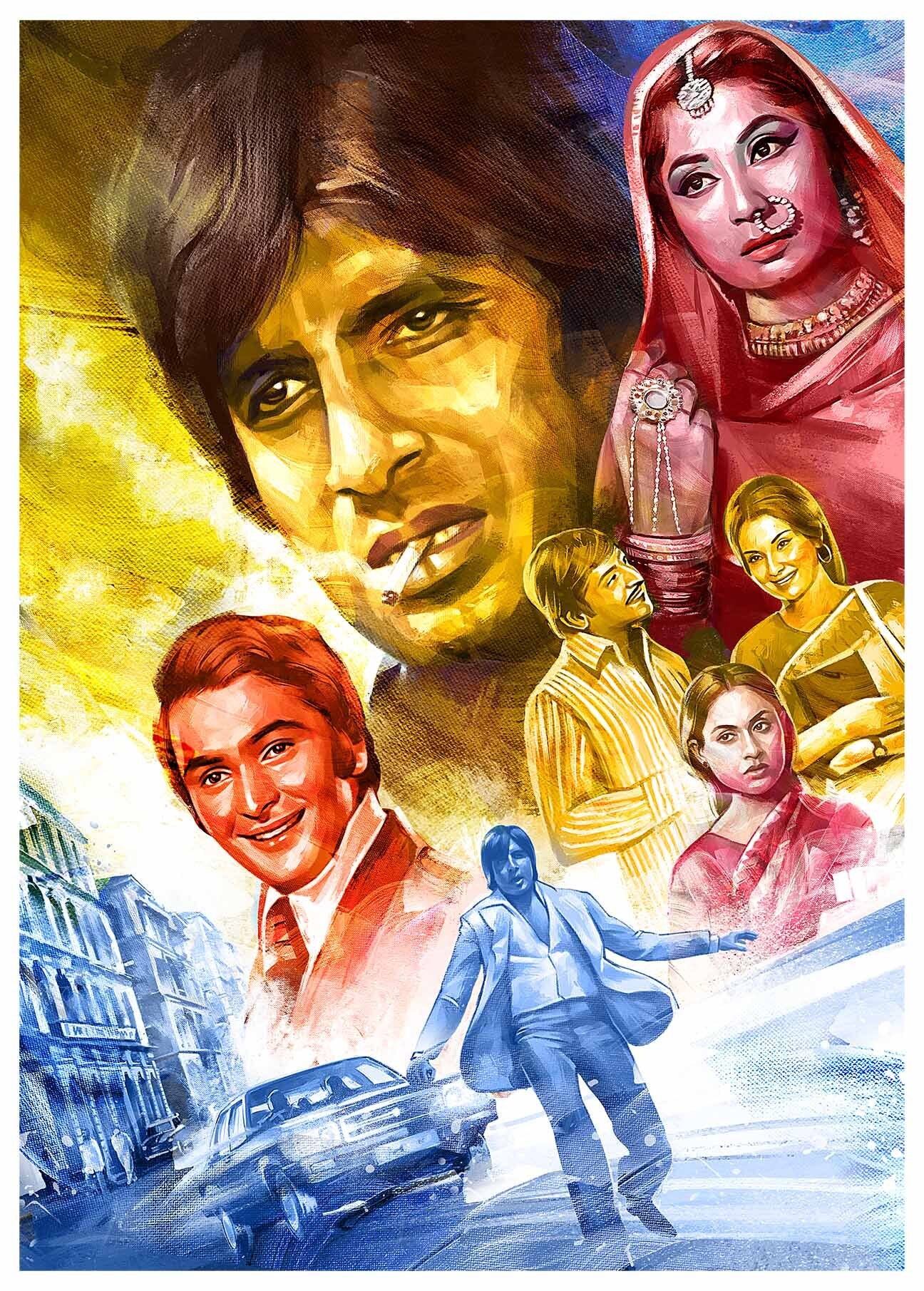

An edited version of this article appears in the annual report FY 2021-22 of Future Generali Total Insurance Solutions. The report was prefaced by a collection of essays on the evolution of Bollywood — what I call Bombay Cinema. Jai Arjun Singh wrote about the 1950s, Dipankar Mukhopadhyay wrote about the 1960s, I wrote about the 1970s, Akshay Manwani wrote about the 1980s, Paromita Vohra wrote about the 1990s, Rupleena Bose — also the editor — wrote about the 2000s, and Suhani Singh wrote about the 2010. Artwork is by Gajanan Nirphale. Each decade has a poster by a different artist on firm paper, which can be detached and framed, in case that persuades you to buy the copy. It is available on Amazon.

At the turn of midnight on the eve of India’s independence, when Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru had spoken of our “tryst with destiny”, he was speaking of India’s tryst, a collective fate of a new nation buyed by a socialist imagination towards a glittering future. In the two decades since, with multiple wars fought, this promise would fray, and we would begin seeing the swapping of the collective for the individual. No longer was it the fate of the nation, but the individual saviour that one tacked their hopes on.

Our films in the seventies, too, produced the kind of hero who, in a clear, coal-sketched outline, could be distinguished from the ordinary. Repeated twice in Deewaar (1975) is the line, “Dekhna ek din yeh ladka zaroor kuch banega.” The individual destiny of the hero is now seen as proof of his innate worthiness, the single-minded messiah. What if it is also seen as the failure of the nation, of the collective? A lot about a nation can be said from the hero it produces, from the hero it thinks it needs.

Rise and Fall of a Superstar: The Rajesh Khanna Phenomenon

The 1970s saw the vertiginous rise and steep decline of Rajesh Khanna, India's first true superstar. Between 1969 and 1971, he flung 15 superhit films, one after the other at his adoring, lusting fans, with not a single flop blemishing this record— including, Anand (1971), Haathi Mere Saathi (1971), and later, Amar Prem (1972) with his iconic line stuck in amber, "Pushpa, I hate tears".

The toast of the town, the eye of a storm of girls kissing his car, a cherry red Impala, writing him love letters, he was on the cover of the first issue of Stardust in 1971, and later, in 1973, BBC also made a documentary on him titled Bombay Superstar.

Journalist Sidharth Bhatia tries to make sense of this lust, adulation, and reverence that was sold as fame, “Rajesh Khanna was every mother's son, every sister's brother and every girl's handsome boyfriend." He formed a formidable erotic pair with Sharmila Tagore—who herself was a very successful actor breaking norms and modes of what an actress was to be—and Mumtaz. Films like Safar (1970), Amar Prem (1972), and Aap Ki Kasam (1974) made it seem that the decade already belonged to Khanna. But then, something shifted with a tectonic force in the way stories were told and received. The wind-swept romance, the gentle slowness of twinkling eyes and soft smiles he was part of were tiring at the box office. He starred in a string of flops in the mid-seventies. There were also reports of his increasing hubris, his unpunctual demeanour making producers froth at the mouth. It was clear that the formula needed to be shaken, to swap one kind of stardom for another.

Enter, the quaking Angry Young Man.

Discontentment of a Generation: The ‘Angry Young Man’ in Cinema

The 1970s seeded one of the most enduring tropes of Hindi cinema — the Angry Young Man. Concocted by scriptwriters Salim Khan and Javed Akhtar, forever remembered as two halves of an en-dash, Salim-Javed, the characters, always brash, brooding, brawny, were given shape by many directors — Yash Chopra, Ramesh Sippy, and Prakash Mehra — voiced and enacted by the baritoned, tall, lanky Amitabh Bachchan with flaring bell bottoms slapping against his long legs as the coolie-turned-smuggler Vijay Verma in Deewaar (1975) or the khaki-clad inspector Vijay Khanna in Zanjeer (1973) who would pursue vigilante justice outside of the law.

This figure of the Angry Young Man followed the framework of the anti-hero, pursuing good ends through bad, or at best, questionable, means. The ends were entirely anti-capitalist, with the villain being a big industrialist or an owner of a coal mine or a dockyard or a construction site. (The textile mills were in a steady decline through the 1970s, so moneyed villains, too, were slowly moving away from being mill owners.)

Money was always a cause for suspicion in this universe. Vijay Verma’s mother in Deewar, played by Nirupa Roy who would be immortalized as the wretched but loving maternal figure, asks, “Kyun beta, paisa aa jaye toh neend nahin aati?” Later, in a moment of hubris, when Vijay lists the things he owns, “Aaj mere paas building hai, property hai, bank balance hai, bunglow hai, gaadi hai, kya hai tumhare paas?”, his brother, played by the charming Shashi Kapoor, replies with a devotional intensity yanking him down a peg, “Mere paas maa hai.” This famous dialogue, used to represent the cloying, cinematic love for mothers, is, when looked at more critically, a manifesto of anti-capitalism. The only antidote to greed, to money, to property, to endless, dizzying growth is rooted love.

It is tempting to embed these films in their time, as though time unrolled a seamless, neat narrative, with the food shortages of 1972-73, the oil shocks of 1973-74, and the subsequent inflation and unemployment producing not just a rumble in politics but art, too. The leaking bloodletting of Naxalbari, the civil rights movement trailing across the US, and student agitations in Europe, the labour movement and Jayaprakash Narayan’s socialist frenzy was snowballing into a rupture in governance, with the Railways Strikes of 1974 bringing the economy to a standstill, and then the draconian Emergency imposed on the country like iron claws. In this context, people have drawn comparisons between Vijay and Haji Mastan — also a dock worker who rose up the ranks to become a powerful smuggler — while seeing in the Angry Young Man a reflection of a generation’s collective despair.

There is always the fear of over-reading these retrospective evaluations. In the book Pure Evil: The Bad Men Of Bollywood Javed Akhtar is quoted at a Kolkata Literary Meet, “We had none of the (prevalent) social and political situation in mind at all while crafting the Angry Young Man. We were not even aware of those to any great extent! Maybe it was good that we were not so close to the situation. Because we could write as writers.” Perhaps the angst, the political consciousness was in the air — imperceptible yet present, not needing to be highlighted, distilled, and articulated so discerningly.

The Bachchan films, growling with agony, were written into the secular fabric of the nation — with the word ‘secular’ itself entering our constitution in this decade, in 1976. While there was disillusionment with socialism and government inadequacy, the secular promise was never questioned. Vijay Verma's coolie badge is 786, a number considered holy in Islam. Manmohan Desai, the flagbearer of logically reckless, emotionally drenched dramas, made Amar Akbar Anthony (1977), reaffirming the pluralist ethos that girded much of Bombay cinema. Even as the film has an uneasy, flattening tendency in etching the Qawwal Muslim and the Bandra tapori-speaking Christian as opposed to the unassuming and ‘normal’ Hindu, the film drove its masala moral compass into the sunset, with the last shot of a car thrusting into an orange sky, foregrounded by green grass and a white horizon — the Indian flag. Even a film like Sholay (1975) — India’s first 70 mm, stereophonic sound film — bursting in its seams with masculine bravado, made space for Imam Chacha, the blind Muslim cleric, a familiar figure in 1970s cinema, with obvious Muslim markers, an announcement of his identity that never feels like a threat.

What also connects these films — Sholay, Deewar, Amar Akbar Anthony, Muqaddar Ka Sikandar (1978) — is that they are multi-starrers, a trend that began with Yash Chopra’s Waqt (1965) and picked up in the 1970s, with films like Anand (1971), Chupke Chupke (1975), Hera Pheri (1976), and Golmaal (1979).

This was part of the ethos of the era — with Amitabh Bachchan, there was always a Shashi Kapoor, Vinod Khanna, Shatrughan Sinha, or Rishi Kapoor to complete the canvas — where directors would cobble films together with such a relentless, reckless pace, often shooting more than one story at the same time, moving around actors and directors across studio floors like pegs on a chess board. This was, understandably, a logistical nightmare as much as it was a cinematic and continuity quandary, with the films of this era full of small mistakes and body doubles. For example, there is a scene in Amar Akbar Anthony where Akbar (Rishi Kapoor) calls Salma (Neetu Kapoor) Neetu, instead of her character name. A body double was used in parts of the climax of the film, because Rishi Kapoor had to be in Delhi to shoot another film against the backdrop of the Republic Day parade.

Desai’s high drama with thick masala plots were the toast of the time. They were brightly lit for projection reasons, for smaller theaters in smaller cities would have older, creaking projecting equipment that would show darkly lit films with terrible grain. In 1977 no less than four films by Desai — Dharam Veer, Chacha Bhatija, Parvarish, and Amar Akbar Anthony —released to thundering commercial success.

Perhaps, for a second, we might have to re-orient ourselves towards what commercial success meant back then. In order to be considered successful, a film needed to run in single screens, which could seat upwards of 1000 people, for over 25 weeks. Amar Akbar Anthony and Dharam Veer, for example, ran for 75 weeks. Unsurprisingly, these films were panned critically, or at best seen with a suspicious eye, with the Times of India critic calling the former “outright hokum… redeemed by the hilarity that accompanies it.” Manmohan Desai used to joke that he would be very concerned about his film if it got good reviews, such was the relationship between criticism and the high priest of commercial cinema.

The Salim-Javed scripts and Manmohan Desai universes, however, scratched their female presence only around the periphery of the plot. Women were reduced to mothers who wept for their child and spouse or lovers who hung around, looped across arms, head on shoulders, providing respite and company, injecting glamour and song, often needing to be saved. A glaring example of that is in Amar Akbar Anthony, where the song ‘Humko Tumse Ho Gaya Hai Pyaar Kya Karein’ had three different male voices used for each male character — Mohammed Rafi, Mukesh, and Kishore Kumar — but for all the three female characters, there was only the versatile voice of one Lata Mangeshkar.

But to say that these writers and directors wrote for the times they lived in would be wrong. For the same decade that produced the Angry Young Man, also produced the Thinking Woman.

Women in Love: The World of Middle Cinema

Even as labour unrest — portrayed in cinema for the first time in the late 1950s, in Paigham — and gold smuggling became a prominent theme, showing a slow disillusionment with Nehruvian idealism of five year plans and big dams, there was still a parallel culture of hope. For example, in Bobby (1973), the film that introduced the flamboyant bravado of Rishi Kapoor and the seething gaze of Dimple Kapadia in a blaze of erotic, young love, we see an image of Nehru pasted on the walls of the dorm room of young Raju. That even as the cracks began to show, there was also the reverence, which like an insistent stain, would never leave.

The urban films, still preoccupied with love — Rajnigandha (1974) and Chhoti Si Baat (1976) — had characters whose lives were made easier by the country’s well-oiled infrastructure, with the female characters always travelling by bus or train, safely and confidently.

The Thinking Woman was part of the rise of Middle Cinema and its emphasis on stories around the middle classes. Vidya Sinha in Rajnigandha opening a book, closing it, to only be lost in her thoughts or waiting in a ruminating pose at a bus stand in Chhoti Si Baat, Jaya Bachchan moping over her textbooks, insisting on being taught botany in Chupke Chupke (1975) or looking at Bombay with the fresh eyes of a lover in Guddi (1971), Dimple Kapadia calling herself a 21st Century woman in a 20th Century film, Bobby (1973), Zarina Wahab's yearning, desiring gaze in Chitchor (1976), Meena Kumari's melancholic longing and clandestine reading of diaries in Pakeezah (1972). These were women studying, commuting by themselves, working, pursuing a life of economic sufficiency, or performing pathos with agency. These were also women who would be forthright about humour and sex, even queer sex. In Rajnigandha, for example, when Vidya Sinha’s character’s married best friend bids her goodbye at the train station after spending days with her, she giggles and whispers, “Raat ko bistar mein yaad aayegi teri”.

Then, in the midst of 1975, the year Sholay and Deewar put urban male bravado for a mostly male audience on the floodlit platform, descended Jai Santoshi Maa, a low-budget mythological tale directed towards rural women, filled with the feminine presence — both divine and human — that shattered box office records. People removed their slippers before entering the theatre, showering the screen with coins, flowers, and rice as though they were partaking in a ritual. Jai Santoshi Maa is what we would today call a ‘sleeper-hit’, a cult film with its devotional and catchy music blaring from speakers for decades to come, and its reference even being used in Amar Akbar Anthony. Vijay Sharma, the director, tried to recreate this mythic mania with Mahalaxmi Maa (1976) and Mahasati Naina Sundari (1979) but Jai Santoshi Maa remained a striking outlier in a decade, as opposed to a pioneer of a snowballing, successful trend.

While the decade coughed up an Amitabh Bachchan, it also sculpted with tender affection Amol Palekar's innocent smile and unthreatening moustache — devoid of any masculine possibilities, unlike the present day insistence of the machismo moustache — in Rajnigandha, Chhoti Si Baat, and Chitchor.

Realistic Nation: The Decade of Parallel Cinema

Alongside this commercial churn of films alternating between the sweet, candied kind and the angry ones drenched in vengeful heroes, was a line of parallel cinema which began in 1969 with Mrinal Sen’s Bhuvan Shome and Mani Kaul’s Uski Roti, made iron clad over this decade, with Shyam Benegal's entry, blurring the distinction between commerce and art. His first five feature films, Ankur (1974), Charandas Chor (1975), Nishant (1975), Manthan (1976) and Bhumika (1977), paved the way for a strong tradition of new wave cinema — lassoing in new talent from students of cinema and theatre from FTII and NSD, like Naseeruddin Shah, Om Puri, Smita Patil, Shabana Azmi or actors like Kulbhushan Kharbanda, and Amrish Puri. Ankur (1974), Nishant (1975), and Manthan (1976) were angry in their own desperate, revolutionary, but ultimately bleak manner.

Set in rural India, away from the noise of the city’s order reflecting on the feudal nature of society, these were movies made out of a sense of hopelessness and a glimmer of solidarity. “Cinema is a social medium, unlike the medium of painting,” Benegal noted in an interview, “And because it is a social medium, somewhere along the line, a sense of social responsibility does creep into it.”

The New Wave, the Avant Garde, or however people choose to label this phase, was aided by Ritwik Ghatak serving briefly as the Vice Principal at the Film Institute of India in Pune in the late 1960s, influencing filmmakers like Kumar Shahani, Mani Kaul, and John Abraham to burst through the scene in the 1970s. What these films through their realistic pace, the lack of a thundering background score, and the refusal for crescendo and catharsis, did was that they made one aware of time in cinema. The tradition of editing says that when a piece of information is conveyed, you must cut away, but these films lingered, creating a space for the inarticulate things, the hazy, unclear intentions to swarm.

What is interesting is that the Film Finance Corporation of India (FFC) funded many of these films, including MS Sathyu's poetic partition-drama Garam Hawa (1974) and even Prem Kapoor’s Badnaam Basti (1971) India’s first gay film, making a case for state investment in art cinema. In fact, its “objectives and obligations” noted that the FFC must “promote and assist the film industry by … granting loans for modest but off-beat films of talented and promising people in the field.” (The FFC would become the National Film Development Corporation in 1980.) Curiously, Satyajit Ray was extremely skeptical of this ‘New Cinema’ and in two essays, published in 1971 and 1974, noted that experimentation must be done to heighten the impact of cinema, not for any esoteric end.

But as this decade arthritically made its way into the 1980s the lines between the new wave and the commercial were getting blurred with artists and technicians floating between the two words. One great example is Shabana Azmi, who made her debut in Shyam Benegal’s Ankur but towards the end of the decade starred in Amar Akbar Anthony, even if the role was entirely peripheral. Even new wave directors were roping in big stars to make films that resonate beyond the film festival culture, like Satyajit Ray’s Shatranj Ke Khilari (1977). The culture of cinema was porous then, a porosity that would, in the coming decades, harden into concrete, where what was once parallel cinema would be rebranded as ‘indie’ performing its cinema at a stratospheric, safe distance from the commercial center where all the money was being churned.

this was really informative!