Sometime in the year 2000, as the millennium turned, the Taj Mahal was made to disappear. The person responsible was the Indian magician PC Sorcar Jr, son of the famed magician PC Sorcar — whose bag of tricks involved sawing a woman in half on live television, causing a meltdown of the phone lines, with concerned viewers calling in.

On the banks of the Yamuna, 400 meters from the marble tomb graffitied with jasper calligraphy and curling arabesques, the slowly corroding pilgrimage of love, yellowed by years of mingling with sulphur di-oxide, had floated away from sight under PC Sorcar Jr’s magical flick of the wrist. “No, it was not mass hypnotism,” Sorcar Jr clarified, “I just kept the Taj away from your eyes. It was a perfect illusion.”

A perfect illusion.

To make things disappear was Sorcar Jr’s calling card to fame — from running trains to British memorials in sleepy cities. He called himself the master of the “Indrajal” form of magic, a “theatrical representation of the wishful dream of living happily, where nothing seems impossible”.

Where nothing seems impossible.

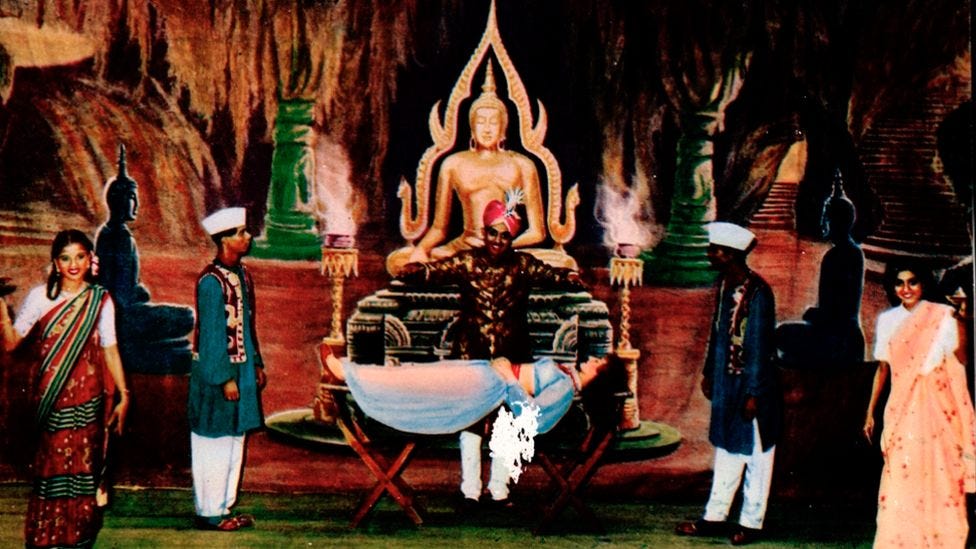

The name Indrajal, like his own name, was an ode to his father, a continuation of that lineage of magic that brewed in the colonial hangover of post-independence. His father, PC Sorcar, premiered his magic show Indrajal or The Magic Of India in Paris in 1955. In a plumed and jeweled turban, wrapped in silk, he looked like he had walked out of the Arabian Nights, whetting the Oriental appetite of the West for the Indian Maharajah. He would begin his shows by drawing a mandala on stage and lighting a lamp before a portrait of Durga. If he was performing Indian-ness, it was a necessary insertion — not subversion — into a magical world where Western magicians would don Indian names to perform their set — Samri Baldwin’s ‘The White Mahatma’, Gustave Fasola’s ‘The Famous Indian Fakir’, and even Harry Houdini who began his career in the mystical arts as a ‘Hindu Fakir’. Magic was considered by the West as the realm of the exotic East, and so the magicians of the West invoked Eastness in their acts as well as their personalities. PC Sorcar was merely appropriating what was already appropriated.

But the word ‘Indrajal’ tethers PC Sorcar Jr not just to his father, but to a tradition, a lineage of artists, magicians, and gods whose trail of breadcrumbs ran all the way back to South Asia’s Vedic period (1500 BCE). Indrajal means Indra’s net. Indra, the Vedic god, who, over centuries would be demoted to obscure mythical stories as the cults of Shiva, Shakti, and Vishnu take over, was considered the god of magic, endowed in the art of sorcery, magical spells, and sleight of hands. In the stories in the Vedas, he casts this net of magic, this Indrajala, to save us and to give us a reason to live. We are still fumbling in the nets.

John Zubrzycki’s Jadoowallahs, Jugglers and Jinn lays out a cultural history of India through the lens of magic. He twists and turns the kaleidoscope of history, telling us of how magic began with and flourished alongside civilization. From references in the Atharva Veda, to troupes of jugglers in Emperor Jahangir’s court who “[produced] effects so strange as far to surpass the scope of the human understanding”, where cocks fought with such ferocity that sparks would emit each time their wings clashed, to Buddhists and Jains using spells and incantations to win philosophical debates, from conjurors reciting charms along the Malabar coast to protect pearl divers from man-eating crocodiles to universities like Taxila which taught magic as a discipline.

What is it about magic that it leaves a trail wherever it goes? Every chapter of Indian history, as chronicled by Zubrzycki, has evidence of people reaching beyond what is normal, what is real, what is permissible, and what is possible.

Noted magic historian Milbourne Christopher has said, “[W]hat a layman thinks he sees and what the magician actually does, are not necessarily the same.” The perfect illusion, thus, rests on the premise of perceptual dysfunction — to see not what is actually there, but to see what is made to be seen, a confected reality.

Magic, thus, rests on the ability to buy into this confected reality, recognizing both that it is confected, performed, produced — that PC Sorcar Jr did not actually make the Taj Mahal disappear — and yet acknowledging what the senses are tricked and awed into believing. To be a skeptic is to be unimpressed by the confection, to wonder constantly the mechanics of this sensual fraud. To be a romantic is to, perhaps, be convinced of alternative worlds riven by alternative logical contours. The rest of us see-saw uneasily between the two.

The point, as I see Zubrzycki is making, is that wherever there is civilization, there is enchantment, and a group of people who insist on persuading you of awe, jolting you out of realism which seems like a natural, unthreatening pillow to rest against.

Magic was considered inseparable from ritual and religion, in fact it was deeply embedded in it. What happened under Enlightenment and the succeeding centuries when theorists like Frazer defined magic as distinct from religion and myth is a separation of ideas which have always been intertwined in Indian thought. Once you separate ideas, the hierarchies emerge, and magic begins its descent. Today, the magicians are hired by governments to promote HIV awareness, and are considered by many to be street beggars. Slums of magicians and puppeteers are being threatened with demolition, if not being demolished already. The first time I had seen a magician was at a dinner table, dressed indistinguishably from a waiter, where he made my father’s 100 Rupee note disappear and then reappear as my father’s creases became visible.

When we speak of magic today, we rarely speak of magic literally — as a magician performing an act. We use the word magic rhetorically, often to mean the movies or literature where its spirit inheres. The feeling — of enchantment, awe, a jolt to one’s preoccupation with realism — is retained as the act of magic itself disappears from our life. When was the last time we used the word magical to refer to an act of magic? When was the last time we have seen magic?

Why do we cry when we see a movie? We know it is false, concocted, an audio-visual density designed to produce tears. And yet. Knowing doesn’t preclude feeling. Writer Joshua Rothes in the preface to his book, An Unspecified Dog, writes, “[S]tories seep into the cracks of logic in order to cement, not to subvert, that reason as a medium for encountering the world is fated to fail in ways that are at once terrible and hilarious and make up the stuff of human experience, in fact the whole of what may be called the human condition.”

That reason as a medium of encountering the world is fated to fail… that we will cry knowing fully well that the tears are in response to a sleight of hand.

Film critic Rahul Desai aptly wrote, in his pan of Atrangi Re, “I’ve rarely been as repulsed and riveted at once.” A fascinating contradiction, if it is a contradiction at all, striking at one of the unsteady barometers of criticism — what to do when you are compelled by art that you recognize as awful or repulsive or riven with political and moral indecencies, and yet, you cannot take your eyes off. What does it mean, then, to be drawn to and strung by the same thing that contradicts all the tenets of good art? What is the “goodness” in good art? If you recognize “good art” but cannot experience it as but a boring lump of deep, quiet, moral stares, what does that say about you?

The film in question — a love triangle crafted with two men and a woman, where one corner of the triangle is actually a magician, a ghost that the mentally disturbed, traumatized woman hallucinates — is like the mythological snake that is devouring its own tail. An image of glorious, cannibalizing disaster. A logical nihilism.

But this was expected. Film director Aanand L Rai and close collaborator, writer Himanshu Sharma have made art out of hysterics, logical freefall, and ambitious, unkempt storytelling. As a friend I watched it with noted, they spend so much time trying to explain the logic of the film, but the logic they front-foot is so painfully overdone, and the long scenes to explain it chafes so shamelessly against the logic of the world we inhabit, it is a bit of a coup that the film even got made. At one point, the hero is performing surgery on air.

On air!

At another point, the train station — a space for the filmic hero and heroine to finally reconcile in a climactic twist of fate as the train leaves the station — becomes the location where the mentally disturbed heroine finally exorcises herself of her past ghosts and her ghost lover and emerges anew. That mental illness is a garb that can be undressed by love is a recklessness which the writer and director don’t see an issue with. To be a storyteller and to be an entertainer are two different preoccupations, one insisting on coherence and one insisting on attention.

I must note that there is something terribly wretched and extractive about our desire for insight from movies and literature. (It is why I tend to find critics who seem to think of movies as vehicles of ideas, as opposed to sensual dollhouses, dull) That we experience art not for the experience itself, but for what it will yield. Cannot watching a movie, reading a book, soaking in a magic show be an end in itself? Does it have to have an aftermath of value?

Magicians, to be fair, were never storytellers. They were entertainers. PC Sorcar’s 2.5 hour-long shows found no need to tell a story, being provocative as they were, enough to keep a bum warmed on a seat. Sharma and Rai are mere descendants of this tradition. As perhaps a nod to PC Sorcar Jr., they even stage a scene trying to make the Taj Mahal disappear.

Aanand L Rai’s last film, the dud Zero where his foul-mouthed, vertically challenged, ego-crested male protagonist jettisons from smallish-town Meerut to smallish-planet Mars with a gorilla in tow, courting physically challenged scientists and emotionally challenged actresses along the way — was that meant to be a spectrum? — was the kind of movie you are more charged talking about and discussing over a toke and a half-ashen cigarette than watching. There is — and this is something people are loathe to agree — a difference between the two. To be in the theater or in front of a laptop is an experience. When we talk or write about it, more often than not we are not transcribing that experience, but translating it, making sense of what we saw as we go along. To write insightfully and to watch indulgently are two separate acts of joy that can but shouldn’t be mistaken for one another.

In my first year as a film critic I had to work on a piece on Tamil film director Mysskin’s filmography, to prepare a guide for the uninitiated. That week wouldn’t end. His films sapped any enthusiasm I had for the artform, wearing its pretensions so crassly, its cinematic influences so brazenly, its heft so charmlessly. I told my editor that I don’t know if I will be able to write this piece — not a single film resonated with me. She told me to be honest about where I am coming from, write it anyway, and later get it vetted by film critic Baradwaj Rangan. He would know best. He read it patiently and thought the piece read fine, but I looked like a mopey child. He had to intervene.

Where was the joy in watching cinema that I had beelined, upturning my until-then entire life to pursue? It was then that he told me the following: To love watching movies, to love talking about movies, and to love writing about movies are three completely different acts, each requiring its own muscle. We often confuse one for the other.

Did I enjoy writing about his movies?

I did.

Then? What’s the hang up?

That we have no control over whether we will love a certain film, but when we take to the empty word document with the restless cursor blinking, like clueless eyelids, waiting to be stunned by insight, we have control, relatively speaking, over that. Which is why writing about films and experiencing films are two entirely different genres of life — one requiring presence and the other insight.

But these two acts can loop around each other till they feel indistinguishable. When watching Atrangi Re, in my head I was commenting on the bizarre brilliance of a certain moment, but did I feel it or did I think it as something to be pocketed and articulated with flesh, later in a newsletter?

Where does feeling end and thinking begin?

The thing about Atrangi Re is that it is so cozily snuck into the worlds director Aanand L Rai and writer Himanshu Sharma have created in the past, it can only be enjoyed from within that confines — the confines of outrageous drama performed in a realist strain. To have women dancing at the wedding of their husbands (as in Tanu Weds Manu Returns and Atrangi Re), to promise an extraordinary event only to fail just as extraordinarily, like the attempt at making the Taj Mahal disappear or the summoning of a shooting star (as in Zero), the drunk articulations of love (as in Tanu Weds Manu and Atrangi Re), the bus as a space for love to gestate, or Holi as a space for love to express itself in full bodied hues (as in Raanjhanaa and Atrangi Re), and even the staple presence of the hero’s best friend (any Aanand L Rai film, except, maybe, his first).

Thus, to appreciate this film is to appreciate what a film can do when it not only actively does away with logic, but when it creates its own internal logic which it outlines in pedantic detail over long, languorous, odd scenes.

Odd scenes.

But what about them is odd? When I was trying to locate the oddness I came upon the word logic again and again. Logic. Since when did that become a barometer to determine oddness in cinema? I grew up watching stories of housewives shedding lives like cats, women peeling off their skin to emerge as snakes, face lifts performed like casual transactions in a market, and characters sprung upon me blindsiding my experience. There was no logic there. But a total submission to a universe.

Mom called me the other day, saying she tried to watch Decoupled, the show starring Madhavan as Manu Joseph, the troll-like author, or author-like troll. For some reason, or no reason at all, she was always in his thrall. She used to call him Maddy affectionately, like all his fans do, as though he was a neighbour. (Before I had to interview him for the show, I spent five minutes saying “Madhavan… Madhavan… Madhavan…” worried I would slip up and call him “Maddy” instead.)

But even mom couldn’t get beyond an episode of the show. The reason she suggested was that the world was so different from hers, she was not able to get a hold of the show. I agreed, but thought, didn’t we watch the soap operas with housewives turning anew in their graves, of women who performed magic, of magic pencils and angelic presences? Those worlds, if anything, were more galactically distant than that of Decoupled. Then?

Have we changed how we see movies, perceive shows, react to art? Has our imagination been flushed with a desire for realism to a point where we don’t know what to do with egregious art? Where did it come from?

Parimal Patil, Professor of Religion and Indian Philosophy at Harvard University, had noted, “The way we understand is historically conditioned.” This was in the context of how to approach Sanskrit philosophy, for Sanskrit philosophical texts presents arguments in a particular structure, different from Western philosophy, that we are just not used to reading.

It was why, early on and perhaps even now, I have refused to take the Upanishads as serious philosophical texts. I thought them garbled, incoherent, romantic drivel. Patil suggests that perhaps my understanding of philosophy, like my understanding of what is odd is cinema, is conditioned by an axiomatic structure I can’t shake off.

That Indian philosophy is not produced for a particular audience. It is more abstract. So when you walk into it with a particular structure in mind, you are totally lost. But is it the fault of the text or you? How to tune yourself into a text, then? Patil calls this inability to tune into a world, the “tyranny of history”. I wonder then, if that makes us, the critics, the tyrants, instead. Producing not just opinions on films but provocating ways of watching films.

I keep going back to Zubrzycki’s definition of magic in his book — “the artful performance of impossible effects”. Maybe Atrangi Re’s performance wasn’t artful. Or maybe we no longer know how to consume impossible effects. And with the ridiculously sensual world we inhabit, we will never know which is which, and which is true.

This was a wonderful read, even for someone with near total ignorance of the films referenced. I loved the structure of the piece, and the skillful threading of the connection between the experience of magic and film. I gasped at “Why do we cry when we see a movie?” at the transition, when I realized what the piece was going to be about.

I learn so much about thinking about films from your writing, thank you.

Superb post, Prathyush! I haven't seen Atrangi Re yet but I loved how you've engaged with the theme and so many other aspects of magic and cinema. As someone who leans more towards movies with a purpose - not in an extractive way but just what I tend to enjoy more, even as an 'experience,' your perspective made me reflect on so many things! Thank you for this thought-provoking piece.