On Darjeeling

Parimal Bhattacharya's "No Path In Darjeeling Is Straight" raked up memories of the hill town.

Last week I wrote about the HBO show The White Lotus, last year’s Booker Prize longlisted book Such A Fun Age, and how perhaps we have reached a place where we can speak of majoritarian identities like whiteness only in terms of guilt or entitlement. I was also very unsure of fetishization as a concept because, like a flexible tree, it sometimes bends so persuasively onto the neighbour’s garden of cultural appreciation and aspiration, it is hard to say it never belonged there in the first place. The book certainly doesn’t help clarify boundaries. Maybe there are none, or there are so many boundaries, each centered to its own subjectivity, that the idea of seeking and theorizing around one boundary is pointless. As always, write to me if you are so moved. Like, share, subscribe.

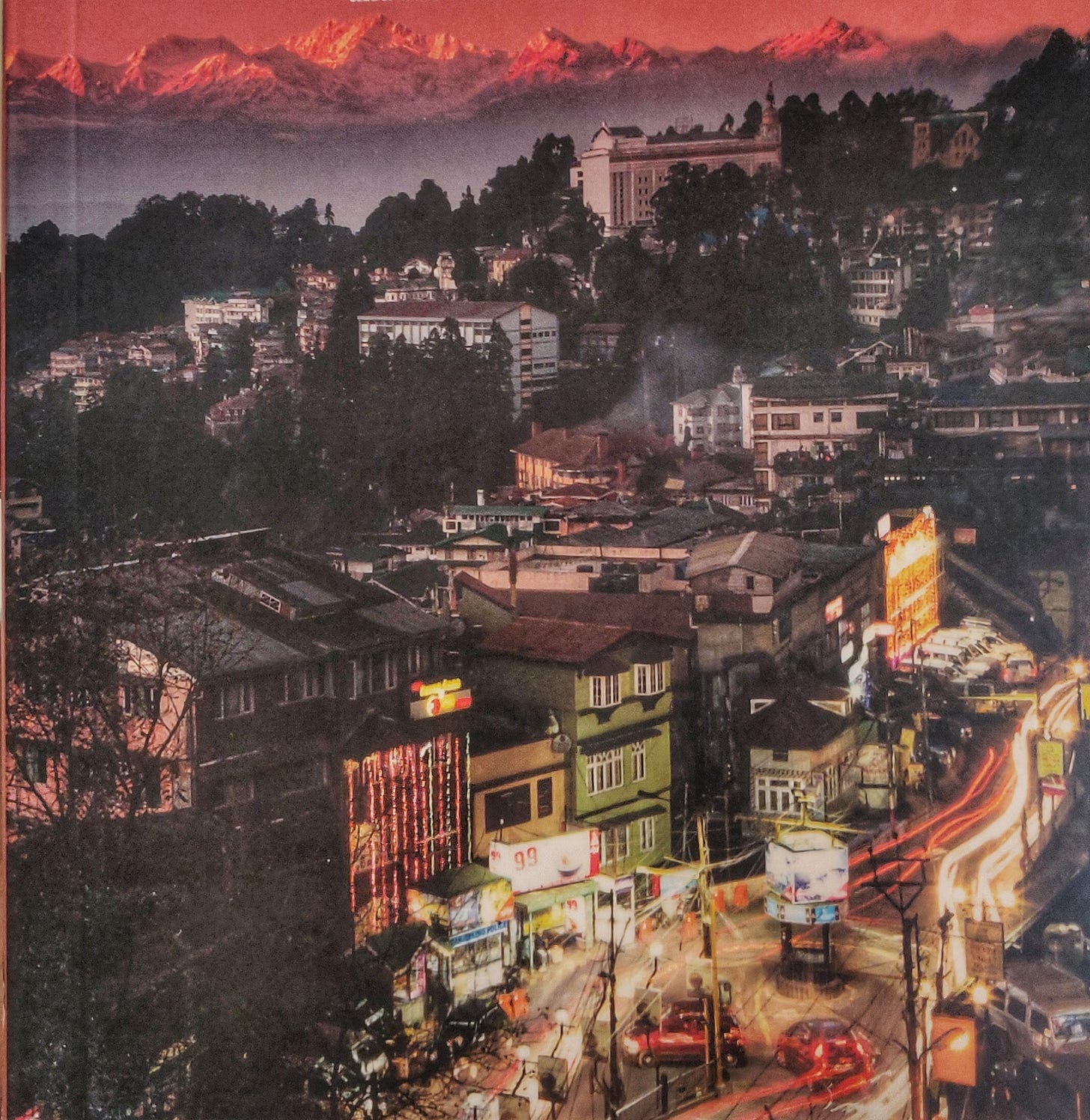

When I walked straight into the Shrubbery Nightingale Park in Darjeeling — a greenhouse in front of me, a patch of inked flowers in between, my muscles languorous from a long walk that cold morning, lubricated by sweet milky tea from the hawkers at the Chawk Bazaar — and swerved left, I yelled, “Fuck”. I remember this clearly, because I don’t usually curse so emphatically, but also, I can never forget what I saw in front of me. The unmisted, magnesium white peak of Mt. Kanchenjunga as if floating mid-air, glowing in the soft morning sun, its snow flinging light like a million broken mirrors.

This was November 2019. From the steaming, relatively soupy plains of Siliguri — the “chicken neck” connecting North-East India to the rest of the country — we took one of the many overcrowded jeeps, 3 in front, 4 in the middle, 5 in the back, winding up in brash speed, clinging onto the serpentine and fogged roads towards Darjeeling. I was with G, who planned and plotted the trip, being a creature known and grown among the hills, G, who paid for boarding while I footed the food and drinks, G, who packed an extra sweater because I was insistent (and incredibly wrong) that my shawl would keep me warm, G, whose accent betrayed his Darjeeling boarding school years, G, whose solution to shivers was hot toddy, G, who is currently his mother’s Facebook profile picture, G, who is no more. He passed away in March this year, and since then I have been staring at the cover of No Path In Darjeeling Is Straight: Memories of a Hill Town by Parimal Bhattacharya rotting in my Amazon cart. The book, thrown up by the algorithmic charms of Amazon, had a cover unlike any I had seen. But I didn’t think I had it in me to read about Darjeeling, because sometimes, the memory of a place and the person who showed you around that place become inseparable. The love, awe, and doubt I felt about him and the place could not be teased apart, because we don’t measure and bracket our way towards feeling. Feeling is always cumulative, unyielding to introspection. I couldn't think of Darjeeling without thinking of him and I couldn't think of him without thinking he was no more.

If I had purchased the book then, Bhattacharya would have clarified my cloudy abjections, for in his book he quotes the Egyptian author Naguib Mahfouz — that is is never about the memories, but rather how it felt to have them. That, thus, it wasn’t necessarily the memories but their feeling that I was trying to elude. That nostalgia is about trapping a certain feeling, and parceling it across time, as opposed to a project of resurrecting events. Which is why nostalgia, when written about, can seem so cloying, so redundant.

I also wanted to read the book to clarify my images of the hill town, because I seemed to have forgotten so much of it. Most of the photos I took then were of him, and not the town, and so I can’t even access my archive in any meaningful way without being waylaid by that tender grief that marks time. Last week I capitulated, and bought the book after Amazon repeatedly reminded me via e-mail of this book lying unbought, rounding up its insistence with a sizeable discount.

Few pages in I recognized that Bhattacharya was doing the very thing I was trying to do by reading him — tracing the contours of a town that is slowly fading in memory. But for him it was also more urgent, for it was not just the memory that was fading, but the town that he knew itself being rendered unrecognizable with every subsequent visit — disappearing phone booths, ATM machines, pharmacies padded with plenty, disenchanting crowds. The book was thus an attempt to calcify those memories before they began resembling myth.

“A return to the city of memories is like masturbation; the mating with memories goes on inside the head. It is followed by the ache of self-deception and guilt.” — Parimal Bhattacharya

He had moved to Darjeeling, a ‘Babel of tribes and nations’, in the early 1990s to teach at the local college. This was a fractious moment in its history because Darjeeling was just reeling from the fiery agitations for Gorkhaland — a demand for a separate state within India, including many regions like Darjeeling. The hills were burning for months, schools and colleges shut, livelihood stemmed in its step, and the production of tea dipped by 70%, exacerbated by the crumbling of the Soviet Union, the biggest importer of Indian tea. The scars were festering, smoothed, somewhat ironically by the sudden burst of globalization that came from the 1991 economic reforms, and the porous borders in the East getting cheap toys and electronics from the Asian Tigers.

Bhattacharya weaves in his memory of that time — teaching denim-clad students who would sometimes walk in with khukhris, sharp knives, and guns, who would fling papers and walk out if the examiner spoke in Bengali instead of Nepali — with choppy history, and syrupy nostalgia, between the founding of this hill town in the 19th Century as a sanatorium, as a reprieve from the summer, the dark, dankness Darjeeling affords, “Home Weather” for the British, to the cold depressions that run through its foam-clouded blanketing, warmed by “guraans, a homemade liquor distilled from rhododendon petals … the yeasty effluvium of raksi… fermented millet”.

The landslides, the “train that would waltz along the winding mountainside” built by the British — the single biggest investment made by the British Raj at that time — and the seats made of concrete or wood erected on roadsides in memory of the departed. There are also lots of graveyards — scientists, travelers, and botanists who lived and loved here, succumbing to malaria or melancholia.

The narrative of the book is winding, distracted like the chor batos it describes — where “no path in Darjeeling is straight … [where] one must step out of the broad roads and take the twisting hill tracks and steep side trails”. The question that the book both asks and answers is can one entirely do away with the broad road in storytelling, reveling in the rivulets instead?

There is, however, also a literary impulse that led me to this book — to read a memoir of a place, that also was a memoir of a person, the place and person alternating in the narrative till the seams become mush. This comes from the dismal chasm between fiction and non-fiction I often find myself wedged in — to yearn for non-fiction writers to write about events with the labouring, filigreed attention with which fiction writers conjure people, and for fiction writers to write about people with the clinical precision with which non-fiction writers investigate events. Every time I swerve from fiction to non-fiction, there is a tonal whiplash that takes some getting used to. So much of the fiction I read is indulgent and so much of the non-fiction dry.

It was a thought experiment that perhaps memoir as place doubling up as memoir as person would be the perfect genre, the “chicken neck” so to speak. I tried Farah Bashir’s Rumours Of Spring, where she recounts her childhood and teenage years in Kashmir as the valley turned its rivers to blood. Her book is woven around her grandmother’s funeral in the mid-1990s and so the book doesn’t move ahead of this time, only shifting its gaze back, to the preceding years that accumulated memory and mourning. The choppy chapters, the lack of a unifying thread of character that is developed, and the unwillingness to get into discerning metallic paragraphs of the politics, both here and in Bhattacharya’s book made me realize that perhaps my thought experiment had it all wrong. To ask of a middle ground between fiction and non-fiction is to expunge from each genre its very endearing elements.

This is to say that Bhattacharya’s book, like Bashir’s book, has a surprising indifference to character and politics. It barely dwells on them for a sentence before twisting its eyeline towards something or someone else. When Bhattacharya returned to the mountains after a decade he tried to search for his Malayali friend, with whom he used to spend rum soaked nights looking at the dark mountains, trying to locate a village from the silhouettes. He found out that his friend had left for Kerala and after finding out his address and writing to him, Bhattacharya found that he had contracted HIV in the hills and then left, moving in with his sister in Kottayam. He had an encounter with a “tea garden girl”, and was sounding repentant about that on the phone. He died in 2007. The very next year The Telegraph put out a news item that read ‘Queen Of The Hills In HIV Grip’, noting with alarm how Darjeeling was becoming an HIV hotspot. Bhattacharya ends the chapter there, and there is no further study of this trend — the reasons, the response. He casually mentions drug pushers without wondering or even investigating the plunge into addiction. His tone reminded me of G who had no anthropological interest in the world. When he took me to his derelict childhood house in Kurseong, walking the winding inroads, sloping up up up, we came across a young boy who didn’t make eye contact with him but greeted him and walked on. G looked at me and casually said, “He’s an addict”, and to my shocked eyes, he responded that the shoulders, the eyes, the hair, it all gives it away, and didn’t bother explaining more, moving on to describing his Marwari friend, who owned a textile shop, whom we were going to meet soon after to see if I could find a Tibetan Pangden — a rainbow riot apron that married Sikkimese women in Darjeeling were wearing. I was neither married nor a woman, but the print was exquisite and I needed to find out if I could get one for me, one for mum.

The more I think of this winding, distracted mode of storytelling, the more I feel like I need to rethink my initial criticism of it. Maybe it is okay to end a book with vortex of unfinished facts and feelings, with no centralizing character or moment to pine over and re-imagine. It is often how we feel after a long, winding, pointless yet occasionally pointed conversation with friends. Why do we expect from literature something more unified and profound? Because we pay for it?

I am reminded, very bleakly, of a night at the Glenery’s basement bar. We were in the smoke room, puffing through a packet, when we came across some people, and G reached out and soon connections were made. There were two airhostess who knew of G because he used to train cabin crew for a rival airline, and an economic researcher who knew of the projects I had worked on. All of them were braised in the mountain air. I remember them trying to explain the view from their respective kitchens asking me to pick the best (I picked the one whose kitchen over-looked a cliff), wondering how long they should take a break before applying for more jobs, if they even want to apply for more jobs, a disillusionment with the economy that G partook in, a love for the mountains that I partook in. They patiently explained the Gorkha agitations, ironing out timelines between puffs of cigarettes and glugs of hot toddy, breaking into Nepali onomatopoeia that G would exaggerate with his hands and guttural screeches. La! It was a conversation swirling around with no discernable fulcrum. At night we walked through inroads, avoiding cul de sacs, strolling by mosques, graveyards, midnight momo sellers draped in flavoured steam, and shuttered shops till we dropped the women off at the taxi stand from where they set off. We would meet the next day too, for tea this time, if I remember correctly. I don’t know what exactly we spoke about. There was a Whatsapp group made. If you asked me to think of that time as a neat narrative worthy of a novel I wouldn't know where to begin. Or end. It’s just a vortex of feeling, as I said, some giggle, some tongue stuck out in jovial abandon, some pointed eye roll at the upcoming visit of the chief minister, some chilli, some sunflower seeds, some milk toffee, some packets of sweets to take back to the plains, to Mumbai, some tea, some potato momos, some imposing sticker on the back of the jeep we left Darjeeling in,

“WE ARE

GORKHA

WE BREAK BONES

NOT HEART”

G laughed at the grammar. I remember that. He would have laughed at the logic too, if he could see the broken hearts that trailed his life. For Gorkhas do break hearts.