On Gehraiyaan's Narrative Trickery

Digging deeper, looking at how the film uses death, infidelity, and trauma.

Why do characters in movies die?

A character’s death is not inevitable or shocking or traumatic or cathartic — it might be all that, of course — as much as it is a conscious, considered, constructed narrative choice made by writers, negotiated and greenlit by producers, staged by a director, performed by an actor. A character dies simply because having completed their duty, the narrative no longer has any use of them. Death, in art, is a narrative creation of convenience.

In Hridayam, there was a college-aged character so pure, so secure, so poor (poverty as virtue, here), so driven, so kind, that a friend seated beside me in the theater whispered that this character is definitely going to die. I shot him a look — how can you say such things?

The very next scene, a hot blistering afternoon, his flesh was flattened under a raucous bus. The friend was right, and I held him responsible for this death.

Having completed his narrative duty — to swerve the hero back on the path of thoughtful consideration — the character is kindly shown the door. I think of Anne Hathaway in One Day. I think of Ranveer Singh in Lootera. I think of Manuela Echevarria’s son in All About My Mother. At least there is dignity in this kind of death.

Sometimes, a character messes up the story so much, knots the strands of morality so thoroughly, that the only way to get the story back on steady ground is to dispense off with him. I say ‘him’ because the two times I have seen this play out egregiously, too obviously — in Shakun Batra's Kapoor & Sons and his latest film, immodestly named Gehraiyaan — it is the philandering, adulterous man who meets this fate. The only way to deal with an irredeemable character, one even the makers don’t know what to do with, is to kill him off.

Death certainly softens the character’s flaws — in life as in art. But that is not why they are hacked off the screenplay. It is because there is no meaningful way for the character to move on from this infidelity without making the film feel like it is endorsing adultery.

Adultery often has moral, lasting consequences in movies. In Guide, there was a moral downfall, when the greed of acquiring love now shape shifts into greed for money, flattening both into debris. It is greed after all that moves one to commit infidelity, what Rani Mukherji in Kabhi Alvida Na Kehna calls “khudgarzi”, selfishness. The director of the film, Karan Johar, even made his characters repent for two years as punishment. A weepy exile of the sexual self.

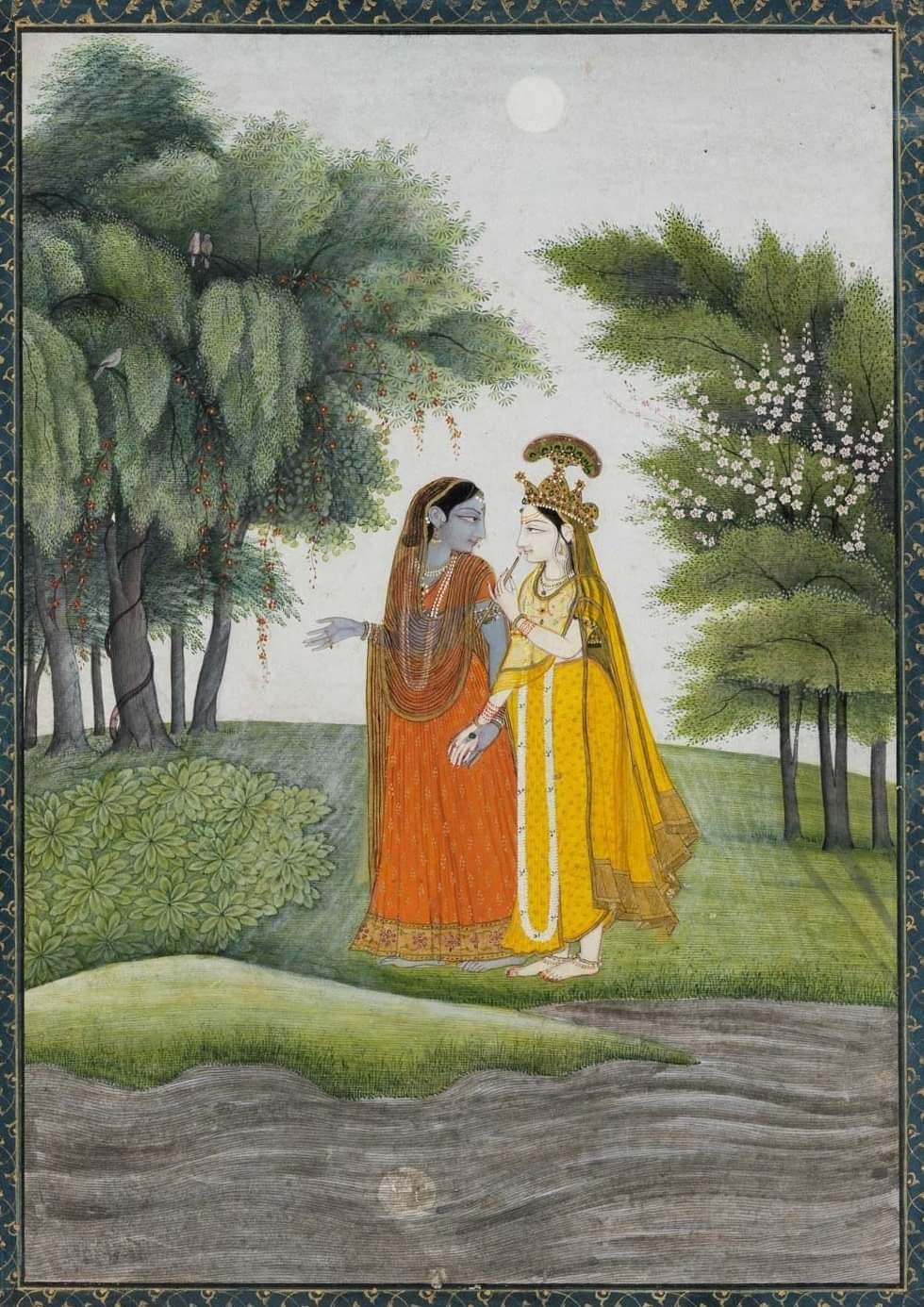

It is not surprising that adultery has always struck a raw nerve in India because it unsteadies the very unit a culture prides itself on, and establishes itself upon — the family. A distinct memory leaps at me, of me asking my father why Krishna cheats on his wife with Radha. He flared up — asked me how I acquired this knowledge, this brazen manner of articulation. I told him, innocently, confused, that it was my Yoga teacher who made this joke, and my father resolved to give the poor man a dressing down the following day. Is this the kind of stories to tell children?

Dad gave me a non-answer — become Krishna, then do what you want. But over the years, the question stained. How does a culture that prides itself so grotesquely on the family as a unit — and I say grotesquely given the debates we are having in our courts where current and former government officers insist that legalizing punishment for marital rape would be “anti civilization”, threatening the family, the children, the men — also produce a god who is the paragon of cheerful, artful infidelity.

Sudhir Kakar in his essay Freud Along The Ganges, notes that famous Vaishnavite saints like Chaitanya Mahaprabhu saw “the adulterous world [as] symbolic of the sacred, the overwhelming moment that denies world and society, transcending the profanity of everyday convention, [forging] an unconditional and unruly relationship with god as the lover.” To see an act that the society throttles as the very act that helps you transcend it. It’s ridiculous how romantic that sounds. As if heartbreak was an aesthetic, not a grieving. Adultery, as Madhavi Menon notes, can be seen in this context as “a metaphor for a desire that moves beyond given notions of the world into an ecstatic realm.” Therefore, any worship of Krishna becomes adulterous — not as an act but as an idea. The act of worship itself is now coded in desire which, over the centuries, weakens into submission. Devotion was perhaps an erotic act once, can you believe it? The temple as a place of eros is unimaginable today, preferring stories of Parashurama who hacked off his mother’s head at his father’s request because she merely thought of another man in a comprising way. (She is brought back to life, don’t worry, when Parashurama’s father, pleased with the hacking, asks him to make a wish.)

But this is all metaphysical, metaphorical speak. The contemporary condition is vexed by a literal-minded conservatism. I will always remember my professor telling me in a frustrated, throwaway moment while walking the corridoors, to never trust a repressed conservative. Victorians were the kind of people, she grunted, who would put expensive table cloths because they were so afraid they would want to hump the table legs if it was visible. I don’t know how serious she was being. I did not want to find out.

And as much as we think we are moving away from this framework of conservative ideas, of family, we are mistaken. Data journalist Rukmini S pulls up a 2018 survey of more than 160,000 households, which points out that 93% of married Indians said that theirs was an arranged marriage — much of it is within the caste. The trends are not much different across generations. The family is the “stable” unit the youth are meandering towards, eventually. That the bends of the river are more circuitous means nothing if all the water drains into the ocean, anyway.

In The World Of Homosexuals Shakuntala Devi wrote, “Homosexual relationships break out of the norms prescribed by the needs of the monogamous nuclear family and … undermine the ideological foundation of the family.” The conservative backlash against homosexuality always betrayed their insecurity of what queerness would do to the institution of the family. This might explain why a film like Badhaai Do with a gay male protagonist and female lesbian protagonist ends in a family ritual with a child at the center of it, holding it all together. It can be argued that queerness changed the shape of the family as much as it can be argued that the family accommodated queerness within it. Who co-opted whom? Gehraiyaan, too, for all its smoke and mirrors fatalism of the family unit, ends in an engagement party — a promise of fulfilled family.

I remember the outrage when Deepika Padukone did the #VogueEmpower video where she noted, “My choice to marry, or not to marry. To have sex before marriage. To have sex outside of marriage.” The moral police grumbled, the dull feminists incensed, the men turned to weepy trolls, but they failed to see that she wasn't endorsing adultery as much as endorsing the idea of women making mistakes. The two seem impossible to differentiate. It’s just easier to have the adulterers weep and repent in cinema, then. It is just easier to have sanitized queer characters, then. Depiction of complexity is often mistaken as a moral endorsement of it. Baby steps they say, as they fumble backwards, drunk in the haze of curdled, day-old milk.

But Gehraiyaan softens adultery, too, by giving us two miserable characters, characters whose misery isn’t produced by, merely compounded by their adultery. It goes to great lengths to give both the adulterers — Deepika Padukone as Alisha and Siddhant Chaturvedi as Zain — a traumatic back-story, the kind of back-story that flattens characters by casting a totalizing spell over them. There are two pivotal scenes where Zain talks about abandoning his mother — a victim of domestic abuse who refuses to walk out her marriage. One when he brings it up with Alisha to address the wounds of guilt he seems to walk around with, establishing a connection, eliciting a vulnerability, and another when Alisha uses this guilt, this trauma against him in a moment of rage. Between the two scenes there is no reflection, no articulation. He merely gives the impression of damage, the performance of damage. It’s too constructed, too blue-grey cool to have any effect.

The psychotherapist Resmaa Menakem defines trauma as “anything the body perceives as too much, too fast, or too soon.” There is something unsteady, incoherent, and messy about trauma, its effect, its articulation. In its depiction in this film, however, all of this sublimates, leaving behind a sharp residue.

I want to ask the provocative question that book critic Parul Sehgal asked in her essay The Case Against The Trauma Plot, “In a world infatuated with victimhood, has trauma emerged as a passport to status—our red badge of courage?” In Gehraiyaan we see shots of Alisha’s mother as depressed, as mumbling, then hanging from a ceiling fan. This imprint on Alisha’s mind — the imprint of her mother’s sadness and her mother’s death — becomes Alisha’s essence. She is merely the sum of her trauma, and that makes her misery both flat and fertile for infidelity. This is not to say that trauma cannot be totalizing, but that it cannot be essentializing, certainly, right? Alisha “bonds” with Zain and together they pour their collective sadness into a pool they stare at together. Alas, it’s a mirage. Alisha’s character is written as though, in Sehgal’s words, she was “created in order to be dispatched into the past, to truffle for trauma”. The writing for Zain is unable to give him the heft of guilt, burdening him instead with adulterous charm and an effortless penchant for lying. It’s all too neat to imply messiness. (As a rule of thumb, distrust any film that uses a flashback to establish motive. It becomes a flat, flabby, affectless appendage to the movie. Nothing moves, because nothing is set in motion.)

There is this naïve belief that if a film is depicting a complex story, the film must be complex too. But sometimes it merely aspires for it, for complexity, for poetry, grasping only a semblance of this reach. That does not mean we should cordon it off, ramming it into the ground by burying it under acidic adjectives and sour adverbs. I am often more excited by flawed movies than I am by perfectly concocted sensoriums. For flaws can be generative — being able to elicit a conversation around cinema that is more robust, more provocative, more compelling.

If cinema is text, the chatter around it is para text, folding itself into the text, kneading it, again and again, till it becomes indistinguishable from it. I humbly submit this piece for kneading.

If you made it till here, I would appreciate a heart, your email id, and whatever else you have to offer.

This is such excellent writing, Prathyush! Thank you for thinking and articulating this. (I'm so glad I got to read this brilliance because of a not-so-brilliant film.)

Thank you for presenting your thoughts in such an articulate manner. For the longest time after watching the film i have read a lot that is being written on it and kind was having a debate within myself over the film. And frankly this piece is the most that has come closest to what i feel too cause i neither fell in love with the film nor hated it too. And am glad as well that it was made even with all its ‘flaws’ cause i agree with your last para.