On Gold-Hearted Hookers In Cinema

The post-colonial sex-worker figure has a lot to say about, not just the institution of sex-work, but the institution of love.

Ab kis gunehgaar ki talaash hai aapko? Ab kis tawaif ko dozakh ki aag se bachane ke liye parhezgari ka kafan lekar aaye hain aap?

(Searching for another victim? Have you come to save another prostitute from hell and carry her off in a coffin of piety?)

- Pakeezah (1971)

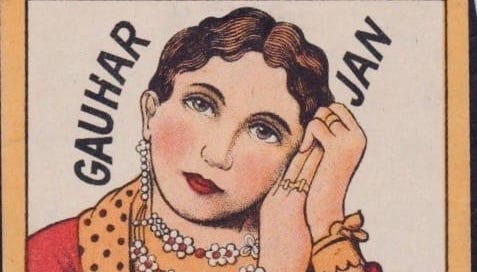

There’s a Wikipedia page for “Hookers with a heart of gold”, and the main image for the article is an oleographic print from the Ravi Varma Press, of Vasantasena, the courtesan character (read: sex worker) from the Sanskrit play Mrichhakatika, a 5th Century CE text. It’s Shakespearean (though of course, Shakespeare was a millennium, and miles away from Shudraka, who wrote the Sanskrit drama) in its court intrigue, duplicitous violence, and stock characters of good and evil. The married, generous-to-a-fault Brahmin falls in love with her, and through the warp of weft of dramatic plotting, all (husband, wife, courtesan) end up happy, alive, and thriving — together.

The gold-hearted hooker (sex-worker, hereon) is a cinematic figure I had first encountered not as a human being, but as a flourish- a performance of the bright and beautiful. Even her despair was poetic, and, in a world that craved poetry, even aspirational. I am thinking specifically of Chandramukhi in Devdas, and later Gulab-ji in Saawariya- women of depth, despair, destined to pine under the cinematic gaze. (If you ask me to describe Chandramukhi, I won’t be able to describe who she is as much as who she performs as- a summation of her palatial mujras and longing glances. All human personalities are performances anyways, but the interesting thing here is the obvious distance that is created between who-she-is and who-she-performs-as, giving the viewers access only to the latter.) Their pining is related to their selflessness, which itself comes from their guilt of being a sex-worker. The gold-heartedness is, thus, not a character trait as much as it is a compensation for that sex-workerness. (If you listen carefully, there is a silent “but” between ‘hooker’ and ‘with’ in hooker-with-a-heart-of-gold.)

These characters are considered easily “available”. And so, to make this promiscuity palpable, you give them the reprieve of deep love they feel towards one client (or as in Saawariya, a non-client), the pining towards whom destroys them emotionally. They are given facades of thick concrete to house their delicate little hearts. Again, the thick-concreteness is not a character trait, as much as it is, like guilt, a compensation for their sex-workerness. Tabu’s character of Saeeda Bai in Mira Nair’s adaptation of Vikram Seth’s A Suitable Boy, is ripe with such reading. She’s steel-faced and pulp-hearted. (The way she rejects Maan despite loving him, the way Gulab-ji gets Ranbir Raj beaten up despite loving him) In the end, she’s alone, and much like in Mrichhakatika, it is her testimony, the testimony of the courtesan in court, that helps acquit the hero. (You can read more about this trope in Western movies, and the classism in this ‘whorearachy’ in this blog on the coyly named site, Slutever.)

It is hard to not think that there is a colonial hangover in this framing. Because in Anurag Kashyap’s post-colonial take on Devdas, Chandramukhi, effaced of tawaif-hood, becomes the modern sex-worker figure, deeply embedded in a back-story of trauma that needs articulation. Suddenly, the modern sex-worker’s grit becomes more important than her gold-heartedness. It is because the system under which she performs her sex-work is also radically changed — it’s not the charged morality of the medieval age, but the capitalist churn. And as such, what she is compensating her sexworkeness with changes. If it was her heart before, now it is the hustle.

In the 19th Century there is a massive reorganization of society around monogamy. The Christian Colonial State is deeply invested in monogamy as a model for the ideal society… The study of Indian sexuality is formative to how we think of Indian society.

— Durba Mitra

I am saying ‘colonial hangover’ because they fixated so much on the sex-worker figure, to criminalize them to such an extent that modern classical dance — Bharatnatyam, Kuchipudi, Odissi — that comes out of courtesan traditions inhered with sexuality and devotion, has now been axed of anything sexual. I have never seen anything as categorically virginal as a Bharatanatyam arangetram, the debut stage performance of a dancer. It is by design asexual, because its early 20th Century revival traditions fought hard to cut any association with sex, instead training the most “pious" and “pure” group — women in Brahmin households. (Again, I don’t wish to paint asexuality as bad much like I don’t wish to paint sexuality as good. My problem is that the obsession of “goodness” that asexuality has among the cultured, is often an oppositional stance- against the slut figure.)

Now, this post-colonial sex-worker figure, while shedding the cloth of gold-heartedness, but still tethered to a possibility of love as redemptive, has provided a unique question- Can you love someone if they are also the one throwing money at you?

[S]ometimes I wonder how different some of my romantic relationships have been from sex work, especially when someone is insisting on paying for your dinner while trying to have sex with you.

— Kristen Cochrane

Garth Greenwell’s book What Belongs To You, set in Bulgaria, teases out this tension agonizingly — in a queer context. Agonizing because, like good art, it doesn’t provide comforting, and bow-tied conclusions, but lends frameworks to look at the messy outcomes of messy actions. (The New Yorker called it part of the Americans-Falling-In-Love-In-Europe genre, a genre I didn’t know existed, or even one that needed such specific framing. But it makes sense, given how Europe has been given an Edenic sheen by American writers — as a loose-fitting, airy continent with both the capacity for British severity And Sicilian sunlight. This capaciousness is often treated as a contradiction by European writers like Madame De Stael- the British severity Versus the Sicilian sunlight.)

Mitko is the young 20 odd something sex-worker the un-named narrator is obsessed with after an encounter in the bathroom stalls. (Mitko is the only named character in this novel where everyone else is reduced to letters- R. or K.) Before they have sex, Mitko washes his dick with the tap water, and as the author blows him, he can “still [taste] the metallic trace of sinkwater from his skin”. The author begins to harbour an obsession, first thought of as strong but fleeting flushes of lust tethered to such details like the sinkwater aftertaste, which then takes its own shape over time. That the narrator pays Mitko for his time and body, gives their affection this monetary transaction as its bedrock, which makes the reader doubt everything — Is the affection that Mitko shows the narrator, calling him his friend, nothing but his gratitude, or perhaps contractual?

Desire and patronage become so strongly intertwined in this tale about that odd, amorphous space between lusting and loving. When does lust categorize itself as love? And when does love catalyze into duty? (This problem gets magnified in Rohena Gera’s Sir, where the domestic help and the bachelor householder fall in love. The problem with the film, which some critics have romanticized for some odd reason, is its inability to distinguish love from duty. If you remove duty from love, and nothing remains, is it still love?)

It is easy, perhaps convenient, to believe that Mitko doesn’t really consider the narrator his friend, that his friendship is a a mere veil to disguise gratitude. Or, if you want to push this to the logical extreme (which Greenwell does in places, but not so explicitly), that he is pretending to be friendly to sustain a money flow- the pretense for patronage.

I couldn’t help but think there is something deeper about the condition of capitalism and commodification at play here. That any affection — independent or dependent on money — congeals on the conditions that produced the affection. If the conditions were a financial transaction, then that can never be erased from the affection. It is always bundled with it. Which is why arranged marriages in India, where one partner is financially dependent on the other, scares me more than anything else. The affection of the dependent partner has congealed on the monthly allowance they need to such an extent that it is hard to extricate one from the other. This makes it not just easy but necessary to make love indistinguishable from duty. There’s nothing differentiating showing affection from showing gratitude.

Given this, the stylistic choice Greenwell employed in this book makes sense— there are no quotation marks which makes conversations, thoughts, and descriptions bunch into these thick, erotic, and deeply profound paragraphs. The way we think about our life, the way we articulate it out loud, and the way we remember it, all becomes one messy narrative to make sense of desire. But in the end, all we can do, as the author does here at the very end, after jostling and blowing and cheating and abandoning, is to lower your face into your hands, and silently weep. Love is love, perhaps because, and not in spite, of the complications.

If you like what you read, tell others. If you don’t, tell me.