On Queer Archives

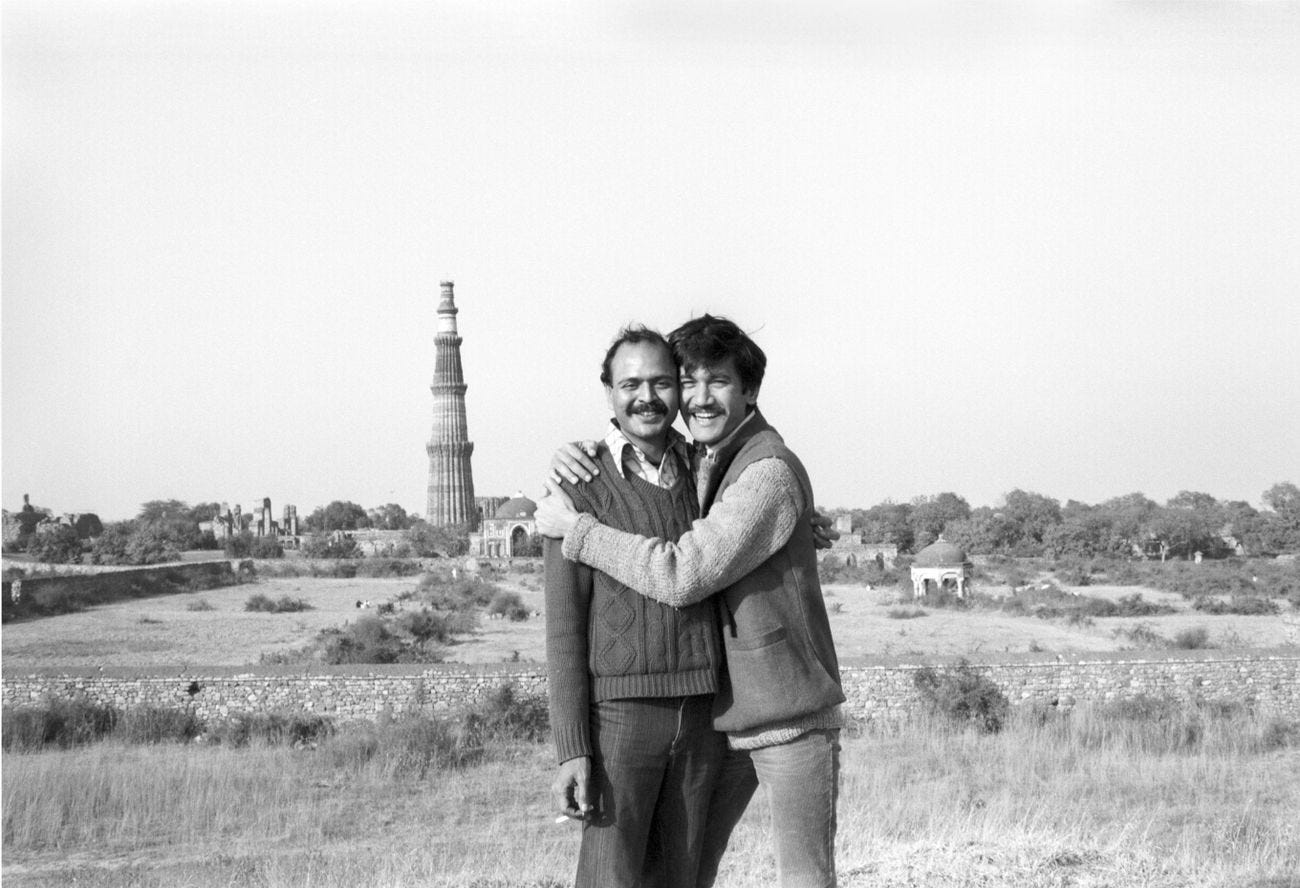

Saleem Kidwai, the noted historian, queer archivist, and translator passed away this week.

Last week I wrote about Darjeeling, a hill town whose beauty my memory never tires of. I follow stray Darjeeling photography accounts on Instagram, screenshotting the sunsets which are very indigo, very sad, very moving, and things rush back for an instant to only recede as the infinite scroll takes over.

This past week Saleem Kidwai passed away — the noted historian, translator, and queer archivist, whose work has informed an entire generation of queer people that we too belonged to history, and are products of it. It’s a powerful notion, I suppose, to consider yourself rooted to not just space but also time. But I have not always, and still don’t always, sympathize with this position — this idea of history and archives as necessary to identity and dignity. I have my moments where I wonder if this impulse to archive and look back to make meaning in the present is a uniquely modern phenomenon — a product of the acquisitive nature of capitalism and the subsequent alienation it produces, requiring something for us to root ourselves to, to explain the disenchantment, the discrimination in a larger, cosmic sense. I am not always convinced of this position, but I have my days. As always, write to me if you are so persuaded. Like, share, subscribe.

While helping research Parmesh Shahani’s book Queeristan: LGBTQ Inclusion In The Indian Workplace I had come across an anecdote from the partly digitized archive of Counsel Club — a queer support group in Kolkata, founded in 1993, dissolved in 2002. It is a story that has stayed with me since — not to make you presume that I think about it every other day, but that whenever I think about this book, it is this anecdote that always first stings .

Counsel Club had advertised itself in newspapers and as a result used to receive letters from all over Eastern India — Assam, Odisha, West Bengal, Meghalaya, and members of the support group used to sit around and write responses to these letters together.

In one instance they had helped a lesbian couple, college going students, leave their family behind in Kolkata and helped them set up their life in Delhi, with the help of other queer and feminist NGOs and support groups. (Years later, the couple acrimoniously parted, one of them married a man and the other has fallen off the radar.)

The following letter, received in 1996, was addressed to Counsel Club “[f]rom a friend to a very close friend”, towards the end of which he made the following request to send a lover for him, “I will ask the person involved to meet me at Cossipur Club Gat, a little away from Dum Dum Junction station at either 10:30 in the morning or 4:30 in the afternoon. There’s a cobbler’s shop near the gate. Please wait there with a coat in your left and an unlit cigarette in your right hand. My password will be “John”.”

The name ‘Jay’ was struck thrice, replaced with ‘John’. The last line on the ageing blue paper read, “NB: Please send my partner as quickly as possible, please.”

There was such earnest entitlement in this request, that the surge of feelings took me by surprise when I first read it. That desire for companionship — love, sex, conversation — pushes us to act in ways we might never have guessed for ourselves, creating the round template we try to fit our square peg personalities in.

I wondered how many mornings and afternoons John waited till he gave up. I wondered where he is today. Is he alive? Is he happy? Is he loved?

Parmesh used this anecdote in the chapter “Historicizing Queer India”, where he looked at queer India from the lens of the archives, from the lens of the various legal fights, from the lens of the various conferences, and to see what bobs of history fells through the cracks.

So much of researching these chapters involved a twin relief. The first was a relief that these characters were not me, that it wasn’t me who was arrested in the summer of 2001 when the police raided an NGO in Lucknow for disseminating information and condoms to counter the HIV-AIDS pandemic, arresting several men for being a front for a “gay club”. The activists were beaten in public, paraded from there to the police thana, not given access to bail, fresh water, and medical attention for the longest time. The following day’s local newspaper read “Gay Sex Racket Busted”. The second was a relief that these characters existed in the first place, for they helped absorb the violence of society, and snowball it towards applications for the repeal of Section 377 — one that criminalized “carnal intercourse against the order of nature” i.e. anal, oral, non procreational sex, and thus, one that expressly targeted gay men, trans people, and NGO volunteers like the ones in Lucknow — in 2001. Pioneers, I realized, must be celebrated not just for what they brought about, but what they endured, too.

But my relationship to history wasn’t, and if I am being honest still isn’t, always so easily framed. For the longest time I was unsure of what I thought of history and archives, especially regarding their place in contemporary society. How much of our identity should we derive from history, more than what it already has bestowed upon us unwillingly? This all came to a tailspin when during the heated debates in 2017-18 around repealing or reading down Section 377 of the Indian Penal Code activists and advocates kept referring to India’s glorious past. They referenced the erotic sculptures on Khajuraho, the erotic texts of Vatsayana, the tradition of courtly hijras, the male pronouns for the beloved in the ghazal written mostly by men, the rekhti poetry, and so on and so forth. The argument was that India has no tradition of discriminating against queer people, and so this homophobic, transphobic law is not Indian in spirit, and thus must be struck down. That the law, like contemporary homophobia, is the gift of the British, and thus an “inauthentic” prejudice.

While I, like most reasonable people, recognized both the violence and the redundancy of Section 377, this line of argument irked me. What if India’s past was expressly homophobic? What if we suddenly unearth evidence of an Indian society that was punitive towards gender and sexuality they considered alternative? There certainly is evidence of punishments and discrimination in religious texts, even if there isn't about implementation. (The first evidence of punishment comes from Portuguese Goa where they burnt a gay man at the stake.)

Besides, we forget how little of history we know, like the black holes of knowledge between the Indus Valley Civilization — which was unearthed only less than 100 years ago — and the Vedic period, or even the black holes that are figures who lived and died in the last 100 years. We do not even know what we do not know — our ignorance is that vast. History is ever evolving as the present pushes towards the future and as the present unearths the past, always poised for things that can undo previous assumptions.

My worry was, and largely is, the usage of slippery evidence that can turn on us to make the case for human rights. The fact that queer people in India should be able to have as much consensual sex as they want should not be dependent on a text written between 200 BCE and 200 CE. It should be based on a shared social contract, that must be universal. To have the dignity to love and sex surely counts. Why bring history into it? (We can argue what this social contract is, but that's another potato to peel altogether.)

I spent the last month of my bachelors degree trying to cobble together this argument — complicating the idea that homophobia is an “inauthentic prejudice” because Indian culture is incapable of homophobia — into a thesis that I presented in an accent that can only be described as Priyanka Chopra-lite.

It was while researching this argument that I came across Ruth Vanita and Saleem Kidwai’s tome, Same-sex Love In India: Readings From Literature And History, published in 2000 — a direct response to a then-perhaps-still entrenched belief that same-sex love is a Western import. The book is a collection of evidence to the contrary. Because then, perhaps still, the idea of history is limited that of ammunition — to be able to collect arguments you can use later. (I remember saying, with the blushed confidence of a fresh, foolhardy undergrad, in a history class that the most use of history I have had was using it to counter arguments of my parents and relatives. My professor laughed.)

Maybe that points to how acidic our lives, our present, and perhaps our civilization is. Where we are unable to appreciate a community until their historical contributions are catalogued. Where we are unable to express the horror of our current political circumstance without invoking Nazi Germany’s genocide, asking “Is this what we are moving towards?” Where we are only able to convince a group of wilted members of the parliament and judiciary about letting queer people fuck per will, per consent by citing age old texts and mythological characters? Where the only reprieve we have while living through tue current fascist regime is the historical waves of change?

I get it, that we have normalized the brutality of our civilization to such a point where we are angry when the Supreme Court calls queers a “miniscule minority” but not as much that we have to actually debate in front of the Supreme Court the rights of people to have sex. The pretense of “neutrality” allowing “both sides” to give an argument, so the pretense of justice can be celebrated. I get it, we have been immunized to this. So much of the laws our society is structured around are flawed, and justice — a concept tied not to ideas but to legal precedents defined and propagated by an elite few — is bestowed not inherited, a privilege not a right. Thus, history becomes a collection of data points that one can and must refashion into arguments in this “neutral” space.

But even in this corrosive condition, Saleem Kidwai’s work seemed like a kind reprieve, one of those for whom history had both the quality of a means — to prove an argument — and an end. His work thus reminded me that history too, like most things, had both instrumental and intrinsic value.

In an article he wrote for Trikone — a Bay Area desi queer magazine — he wrote about a raid at the Trixx nightclub in Montreal, where the “leather- Levis crowd” hung out:

“I was paying for my beer when the Truxx was raided in fall of 1977… We were ordered by a cop on a megaphone to face the wall, raise our hands and place them on it. We waited while we were thoroughly frisked and insulted by the police. And then charged with being `found ins' in a `bawdy house!'… I don't remember how long we stood thus but I do remember that my arms began to ache.” — Saleem Kidwai

They were packed and sent to a police station and later a detention center where they had to pull their pants down, while a doctor shoved cotton buds into their rectums to test for STDs.

A lot of people in his obituaries cited this piece and described this raid and arrest moment as seminal for his decision to come back to India and pursue justice for queer people, because it made for such a compelling narrative of a hero, a plot point in a biopic that plays in our head in his honour — the impetus for social change from the carceral, punitive system. But if you read the piece, there is no such causal assertion. He had to come back to Delhi University (DU) because the leave that he took from DU to pursue graduate studies in Canada was coming to an end and he had to return. It was then that he also noted that he refused to listen to people who suggested he look for a job in North America. He refused thinking that if he was going to contribute to change, it might as well be in India, ironically the same country whose custom department would send show-cause notices to activists for distributing Trikone in India, the very magazine he would go on to write for, a magazine they considered “derogatory to the morality and social systems of our nation”.

His move to India was, like his attitude towards history, both instrumental and intrinsic. He never shied away from this duality in his writings. I appreciated that because it is so easy to believe you are the hero of your own story.

“[Saleem Kidwai] was also keen that our own histories be documented, admiring the posters, memos and assorted scraps that Anjuman, the students’ queer collective at JNU, had carefully archived and preserved. At a time when the law still designated us all criminals, a new generation was nurtured and taught by those who came before us.” — Mario da Penha

I don’t want it to seem that I think history and archiving is unimportant, or even devalue its instrumental value, of bringing it up in debates or dialectics. Of course in my personal life I don't think I have moved my parents or relatives in any direction other than anger by using history. But there are better examples. For example, Kidwai’s writings were used in court cases. The senior lawyer, Anand Grover, noted that his book “became a bible for those of us fighting to get rid of Section 377 of the Indian Penal Code (IPC).” In the Supreme Court verdict on September 6, 2018 which read down Section 377, this book was cited in a footnote — it was used to “demonstrate that same-sex love has flourished, evolved and been embraced in various forms since ancient times.”

During Kidwai's Zoom memorial yesterday Grover pointed this out again. How the court verdict was a “reclaiming of our culture” — how by reading down a colonial homophobic law we have become authentically Indian somehow. My gripe is, why can't we, instead of using the existence of bawdy lesbian poetry in medieval India to reconstruct this idea of authenticity, this idea of history as a reference point, use history as a foundation? Instead of citing cultural authenticity, cite universal morality instead? Why are our courts moved more by history and not the contemporary condition, moved more by precedent and not context?

Besides history also has the power to move us, to seethe us. Queer art, so much of it like The Normal Heart and The Great Believers soaked in the AIDS crisis, was my introduction to queerness — the erotic longing and the dismal tragedy and the anger, the depleting yet mobilizing anger at an administration that refused to do anything about the “Gay Plague”. By the time they acknowledged it, in the mid-1980s, 5500 men were dead. The anger of the indifference of institutions to human life, history can teach us that too. To create an archive today is thus to acknowledge that someone in the future will look back at this, and recognise the violence that we now could do nothing about. So we collect evidence hoping for a future trial.

But if archives are merely evidence for future we won't live through, if history is only a tool to counter the right wing narrative of purity and a pristine pre-Islamic pre-colonial Hindu civilization — and if anyone is looking at the catalogue of historic non fiction coming out of India, it is easy to believe this — then there is a sense of existential futility, because history and archives, in this case, is often not reason that leads to a conclusion, but a conclusion in search of a reason. The bigots are convinced of an ahistoric position, and for us to use history to puncture that is like using pitchforks to light memorial candles. How does any argument work if you do not have some shared beliefs to begin with? Everything will be at cross-purposes. We'll be preaching to the choir, and not the infidels.

Similarly, I recognize the value of an archive as context-generating, but am wary of its limited effect in changing perceptions. Pawan Dhall, while researching his book Out Of Line And Offline: Queer Mobilizations in 90s Eastern India had told Parmesh about how the queer movement in India is often seen as synonymous with court cases — the community mobilization pamphlets, conferences, resource booklets are often not brought up in this discussion. He told Parmesh, “It is important for us as we move forward to look at the past. There are lessons in the past we must keep in mind. It is difficult to explain this… but you cannot move forward in a robotic fashion.” His archive, thus, became another source of history, in addition to the court cases.

When I had interviewed him and asked him about what it is that we can learn specifically from archives, Dhall spoke in a this-that fashion gilded by his nostalgia for the older generation of activists. How they would organize people, mobilize action, a semblance of fighting for one thing together. It wasn’t specific. It had the quality of a platitude, something we say enough times for us to believe it as truth.

The thing is, I am not sure how to react to platitudes. There is an instinct to completely reject it on the outset, but there is also a worry that maybe there is a seed of truth embedded in the platitude and by completely rejecting it, I might be throwing the baby with the bathwater. Maybe Dhall’s attachment to an archive is more about an attachment to a kind of activism that no longer exists.

In his book Out Of Line And Offline, there is a sentence that took me off guard, “I now meet only one of the seven founders [of Counsel Club] off and on, though four of us still live in Kolkata.” This feeling permeates through the book where the many people he interviewed were unable to find themselves in a new era of queer activism that is more diffuse, more divided, more radical, more intersectional, more constrained, more powerful, more disillusioned. One of them, an active participant in the support group through the 90s, notes that he “has not felt the urge or energy to network or get involved” with the queer activists in his town. The value of an archive here is perhaps an attachment to the time that produced the archive, as opposed to the archive itself.

Then, there is the value of an archive that gets highlighted only when it is poised to disappear, when its existence is threatened. So when eBay is refusing to sell leather magazines with detailed how-tos on fisting, magazines like American Bear, Bear, Daddy Bear, and pornos, the value from these magazines, as noted by the historian Vi Johnson is to recognised and serve as a “proof of who did it, what was done, and who was there”. To see Timothée Chalamet on the red carpet wearing the harness, and to appreciate its roots, noting its subversive origin among the queers of the 60s.

I find this argument fascinating, that in an increasingly assimilating population, the archives serve as origin stories of the various strands that assimilated. I remember in Jeremy Atherton Lin’s memoir-memorial Gay Bar: Why We Went Out, he talks of being post-gay, where you are gay but over it, “The dissolution of identity is the ultimate civil rights achievement.” In such an argument both history and archives serve no purpose in arguments because the society itself has moved beyond their instrumental usage. It is mostly contextual, and the historians worry that contextual history is not enough. That for history to be merely contextual is perhaps a signal of depleting importance.

But you know, there are days I am reminded of museums as spaces of mediation and meditation, walking out of SF MOMA or the museum in Old Dubai, without a sense of having learned but only having experienced, and I can't think of a reason why archives and history cannot be valued in the same way. One day, in the bright, assimilated future where we can value things for merely what they are.

For now, whenever doubt arrives like a prompt Amazon parcel, I tell myself to pivot my thoughts to writer Garth Greenwell’s motto, a line from the Frank Bidart’s poem Borges And I, “We fill preexisting forms and when we fill them, we change them and are changed.” Greenwell uses this to hone in on the idea that in art we cannot make anything great without knowing the great things that have been made before us. But to tap into this tradition, this history, is to not just be changed by it, but to change it, too.

To not look at history and tradition as an imposition that only gives. To be a sonneteer is not just to tap into the tradition of sonnets, but to expand the idea of a sonnet, too, “This sense of reciprocity with the past—that the past and the self are not monoliths but dynamic things that change through their encounter with one another—is the idea of tradition that strikes me as most beautiful and most true.”

To think of history and archive is to also think about them, about their value, and their intention in our times. To think of John waiting for his man with an unlit cigarette and a coat. But to also think of John as a survivor of history, nourished by an archive, and later a book — a survivor that tells us that the legacy of queer activism that led us to where we are today included men who just wanted to love.