On Teenage Sexuality In Elite And Euphoria

What is the enduring allure of the teen drama genre?

Last week I wrote about Haseen Dillruba’s unfounded fascination with complexity. I used it to mount an assault on “grey characters” which I note must be earned and cannot be wished into existence by intention alone; that to be edgy is to be a swirling tensile creature who can snap or snag at any time.

This week I am putting the weeks of bingeing shows with adults playing teenagers having lots of sex to some use. Write to me what you think.

Doreen St. Félix begins her New Yorker review of Euphoria with the following conclusion, “Attempts to know the soul of the new generation always tremble with the fetishes and the embarrassments of aging ones.” That older generations, while trying to tell stories of younger generations, often stumble upon their own ignorance. That no high-schooler punctuates each of their vocal fry inanities with “slut” or “bitch”. That no high-schooler, probably few high-schoolers, would look at each other, doused in the heady fractiousness of Molly, standing in a room of mirrors, and condemn themselves to become their “most confident, bad bitch version”. That no high-schooler, probably more high-schoolers, would look at their virgin best friends and exclaim, “Bitch, this isn’t the eighties. You need to catch a dick!”

Created by Sam Levinson, a recovering addict himself, Euphoria, a teen-drama filled with sex, sexuality, and addiction, comes from an Israeli show, adapted to the American suburbs. Levinson has given interviews noting how his personal experiences were folded into the show. Though the fact that it is set in the suburbs tells us something — an artistic liberty to set it in the times we live in, but not too much. The city, like the roving world around, is a train ride away. One of the few references we have of the outside world is the 9/11. The rest is an incubated world, prone to excesses. Levinson uses the imaginary suburb to lens the dreamy orange orchards they cycle through, the empty noir-lit streets at night, and a teen fantasy that is irresistible on the uptake, but which slowly lags as the episodes progress.

But the point isn’t the show’s credentials as opposed to what it is trying to do — redecorate the coveted genre of teen-sexuality. It darkens and deepens the fantasy. The central all-knowing narrator is Ru (Zendaya), a recovering addict. She speaks of sex, rape, violence, affection, fear, nostalgia, and love in the same a deadpan nihilism. Her monotone is compensated by the restless, swooping, swirling camera, a source of visual tension. As it darkens the tone with death and murder looming not as pulpy consequences, but real, affected realities, it even deepens its sexual fantasies, with the women being shown bare-chested, and a flood of penises.

Ru makes a distinction between horrifying and terrifying dick pics, which my friend and I both agree is one of those things you would like to make sense, but really doesn’t make sense. To quote Eileen Myles whose poem dropped in my inbox, “It sounds like a good line but it takes more than sound to make a good line.”

The questions was raised. Is the sex gratuitous? Are we glamorizing teenage over-sexuality? Why so many penises? The questions mount.

I just recovered from an Elite binge. The Spanish teen drama, spanning four seasons, follows the richest of the rich who congeal onto a high-school where you can bare your midriff, wear fishnets, turn your collar up, clutter your neck with gold, and fold the ends of your shirt till it crumples over your elbows. Poor kids are let in with scholarships, and over the seasons, the class-based animosity lends to companionship, friendship, and even love as murders, disappearances, and revenge rove the corridors of the school. It is sexy, and in between teen infidelity, voyeurism, thruples, and incest, it is also oddly nuanced. For example, there is a gay couple who are constantly battling circumstances to be with each other. They cheat, but they come back, and in one scene, the cheated-on demands to know exactly what went down. When the cheating partner then goes on to narrate the sex that happened, he pauses concerned, “Are you angry or are you horny?” It isn’t an excuse to cut-to another sex scene, but a genuine concern about the constricting yet comforting idea of monogamy.

There is the recognition that a world beyond exists, that college will divvy them up. For example, Lu, one of the characters who aspires to study in an Ivy League, increasingly, over the seasons, starts using English words in between the Spanish. Every time she does, there is a jolt, a recognition of the impending. The show is designed to show how each of the kids take control of their own lives, almost at the expense of their parents — one of the single mothers is a drug kingpin, one is an anxious alcoholic, one is perfunctory, one is rich and doles out money as favours. That controlling figure seems missing, which amplifies the rudderlessness. Additionally, them being in high school means they have lived and grown around and with each other giving their relationships this lived-in, tensile quality.

It is fair to wonder why we have more high school dramas than college dramas. I can only submit a theory. That college represents for most people a space of unfettered being, relatively speaking of course. That high school, for most people at least I think, still represents curfews and constraints pads the viewing with a shock that can double up as jealousy. The glamour has an impossible quality. But then there is also the more troubling aspect of underage drinking and sex. Consent becomes tricky when two 16 year olds are trying to have sex with each other. Additionally, living with parents always gives more scope for drama. Don't we know.

It is odd to see teenagers fight over whom to have sex with, as opposed to my teenage years when we mostly were just stuck on the “how to have sex” part. (I really liked how Never Have I Ever provides some sort of corrective of realism to this, where Devi with her friends google Kegel exercises which she hopes will help her “pop her cherry”.) This is the kind of storytelling that isn’t even attempting to be relatable. Its stratospheric glamour is thus all the more alluring.

Besides, these shows are easy to watch, it has all the trappings of fantasy — teenagers falling in and articulating love and lust with an ease that never came naturally to me then or even now, the easy lull of drugs and sex, the peripheral parents, and the exquisite and deliberate fashion. For example, one of the characters in the fourth season has a series of silver safety pins holding two ends of her top together, a DIY abrasiveness that is so like her. The pins show up again in the last episode, all placed side by side on her headband.

The question then comes, is Levinson trying to get at “the soul of the new generation”, if such a thing even exists. I think there is an ease with believing that a story about a character is supposed to be a story of all such characters, the burden of representation that is easy to bestow on art that is increasingly seen as a responsible, cathartic project.

This is not to say that Levinson wasn’t trying to make a show that reflects the times. It is to say that sometimes by bracketing specific stories as cyphers, we forget that the makers didn’t care enough about teenagers to have some of them assist in the writer’s room. They just wanted to make something that worked. The profundity is an added bonus.

The Britney Spears-ing Of Teenagers

It is easy, perhaps necessary to wonder about the morality of such a popular genre. Most if not all actors playing these teenagers aren’t teenagers themselves, and so what we consume is an idea of a teenager, written, directed and acted by people increasingly distant from this demography. For example, Joshua Safran the executive producer and writer on the original Gossip Girl is also the executive producer and showrunner on the Gossip Girl reboot, 10 years later. While Safran graduated age brackets, the show’s demography remained the same — rich New York high schoolers. (Best described by Vulture as “a show about clout-chasers and backstabbers growing up and growing apart, good sex, bad parents, and carrying the right handbag.”)

The question of relatability is thrown out the window, because honestly, no one wants to see versions of themselves as they are. The more interesting and sticky question is the optics of it — of middle aged men writing teenage characters having a profound amount of sex.

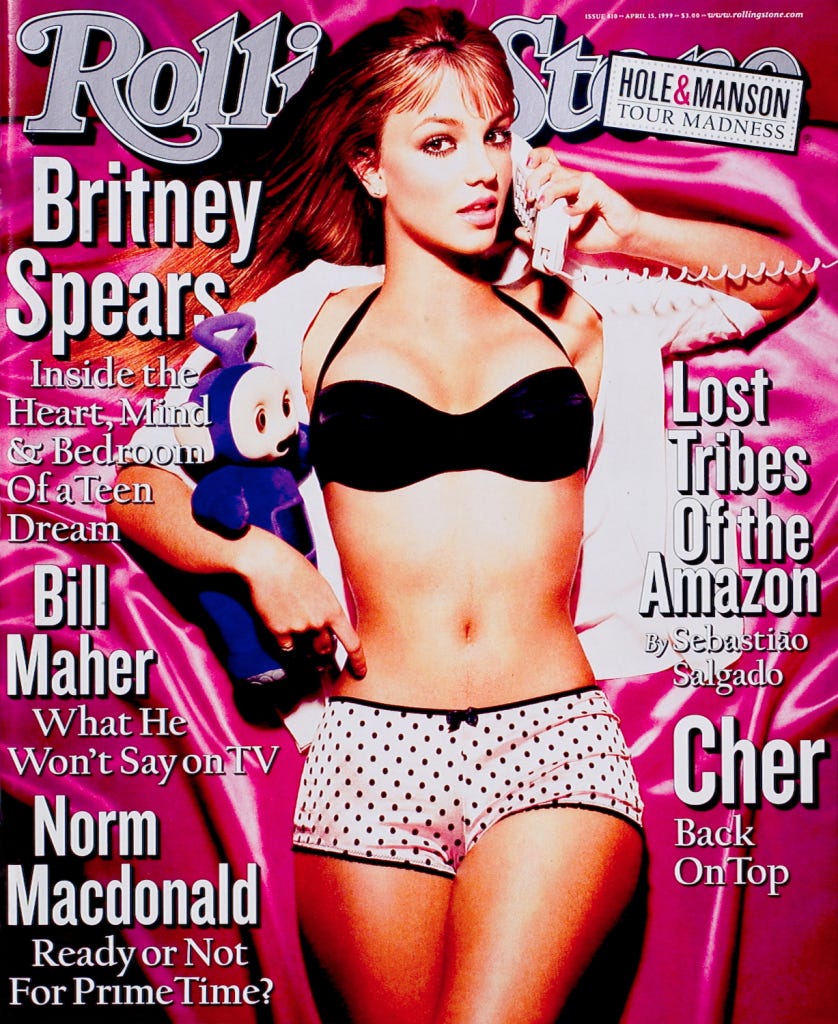

The sexual enigma of teenagehood cannot be denied. Britney Spears was 16 when she struck fame with the three-beat opening sound of ‘Oh Baby Baby’, dressed in pleated skirts, with a bare midriff — her ideas. She was on the cover of Rolling Stone in her underwear clutching a Tellytubby, on a chorded phone. On a podcast discussing their New Yorker piece on Spears’ conservatorship, Jia Tolentino notes the following:

“She fulfilled, in this incredibly complex, confusing, charged way, this combination of innocence and knowingness — the fear of young female sexuality, and the craving of it at the same time.”

On YouTube, one of the top comments for the song reads, “Iconic song. It is weird she's only 16 in this though. Kinda creepy looking back on it.”

It’s the kinda-ness of it that confuses me. To look at a teenager perform their sexuality successfully is confusing if you as an adult like it. To thirst after an adult playing a teenager performing their sexuality successfully is a comforting workaround. Because with the latter there's not much guilt or doubt involved.

I have always felt that age limits for consent, alcohol, voting, while necessary, are also arbitrary. That they can also be weaponized against you as a teenager is something Euphoria dealt with well. When one of the characters, a minor, sends nudes like most teens on this show, she is threatened because according to American law if you are under 18, even if you are sending consented nudes, you could be charged for distributing child pornography.

When in a UNICEF workshop in Kolkata that I was helping put up, a psychologist was explaining the differences between a teenage and an adult brain to a room full of high court judges, something struck them as odd. The workshop was to educate the judges about the new rape laws, and the reasons for their amendment post the 2012 Nirbhaya gang rape. (One of the perpetrators was 6 months shy of turning 18, and was thus tried in juvenile court and later released in 2015. The same year the juvenile justice laws were amended. He is now works as a cook. The other 4 perpetrators were hanged to death.)

The judges were confused because the psychologist gave slippery assessments of what the brain does at different ages with different people, while the following session provided strict boundaries of age limits. How to reconcile the two? It was funny, at first, because it was one of the formative moments when I realised that knowledge is not meant to make things more clear, but to muddy the very idea of clarity.

A guy once told me a story about the first man he had ever dated – an older artist. And this annoyed his parents because they thought the artist was taking advantage of him, who was underage at that time. He giggled when describing this man, as if it were part of his teenage rebellion.

In my head I thought of the romance of the artist figure as a lover. And then I thought of the legitimate fears of a parent with a child dating such an erratic figure. Then I thought of him.

To be told not to date someone was fodder to make him date him anyway. To protect him would be, thus, similar to pushing him into the arms of the very thing he needed to be protected against. The romance of it, all false notions and Tumblr posts, pads all the satanic machinations. At the end of the day even he didn't know why he dated whom he dated. All he knew was that there was drama, and that was enough for him to keep pursuing the artist figure. I don't remember how that story ended.