On Truth & Personal Essays

My growing discomfort with personal essays, with an idea of "literary truth", with writing and reading as noble acts of personal growth

Last week I wrote about Chimamanda Adichie’s viral note, “It Is Obscene” whose language I loved and whose message I found questionable, at best. I am growing more and more disturbed by my ability to feel these things simultaneously. To appreciate the logic of an argument against trans women competing along with cis women in sports, but to be distraught by its implication, by its inability to think of trans women as people before logical categories. I remember at one point when I was told that homosexuals shouldn’t exist because they serve no evolutionary purpose, I googled and noted research papers that emphasized how gay men’s lack of procreation is compensated by increased virility among their relatives. It was then I realized how silly I sounded. That even if this was true, which some studies claim, why should I have to explain why queer people exist? We do. Logic is, more often than we think, a front to disguise personal discomfort. Tanya Aldred in her Guardian piece I linked above, at the end, asks for data to change her mind on letting trans women compete in women’s categories. What kind of data would one need to believe they are being fair? How statistically significant? How many trans people should be there as data points — what sample size? Why this logical acrobatics? Logic has limits. Besides, do we believe in what we believe because we came to it through evidence, or did we start believing something, and then slowly build our fortifications of logic around it as an aftermath?

So much of thought and thinking is messy, and my growing disillusionment with the idea of “truth” is something I wanted to talk about here. It is something I tried to articulate in my review of Salman Rushdie’s frustrating collection of essays. Additionally, I wanted to write a separate piece on why I am wary of personal essays and autobiographies, but thought that fit here. So there’s that as well. Please subscribe, please write to me, please like, please comment. I am assuming you are here for the words, and not just my killer good looks.

One of my favourite professors in college is a man who taught “The History Of Economic Thought”. Everyone hated his class because it was too abstract, too difficult to understand, and therefore difficult to master. I am not saying I understood it and therefore I loved him. But that I didn’t, and he pushed me to make sense of it, failing more often than not, but trying nonetheless. His wife is a pastor, and he invited me to their home for Thanksgiving when he knew I had no other plans. I baked samosas and used all the kahva tea leaves I had to make two big pots. Their house was full of people from their wide social circle — he had lived in Bosnia for a while so there was a lot of garlic and Bosnian. I was seated next to a woman who fought against the apartheid on the left and a lavender farmer on the right. He gave me a lavender stalk as we parted, and it’s still somewhere, pressed between one of my books. There was also a very handsome graduate student, I think, who lived in their basement for free — they do this every year, a new graduate student to live under their care, literally.

My professor hated Murakami. Over dinner he noted how every work of art asks one pertinent question. If within 50 pages you cannot figure out what that question was, the work has failed. He couldn’t locate the question in Murakami’s IQ84. I took his word as prayer and used it rigorously while reading and watching. My first few months doing film criticism was filled with me asking that question, falling short of getting an answer I liked enough to write about.

Now, of course, I think that is a dangerous notion. To think that art can be boiled to one question. To think that anything can be boiled to one thing — one question, one answer, one clue, one truth, one tether between the beginning and the end.

A logical conclusion from my professor’s notion would be the idea of truth. This is something that is picked up by writers writing about writing. Harold Pinter in his Nobel Speech spoke entirely about truth, beginning with a distinction between literary truth — where truth is elusive — and political truth — where truth is negotiable. Salman Rushdie quotes from that very speech in one of his essays in Languages Of Truth: Essays 2003-2020. He calls Van Gogh’s impressionistic paintings of a starry night “far more truthful, even though far less ‘realistic’”, and is squarely on the side of the magic realists, the “wonder tales” which “tell us the truth about ourselves that are often unpalatable”. He argues that art has an essence. But what is this essence, this truth? He offers little by way of answers. Some platitudes about exposing “bigotry, [exploring] the libido, [bringing] our deepest fears to light.”

I wonder why it is that he so fiercely believed that every good work of literature has truth in it. It slowly dawned on me that Rushdie and many like him, like George Saunders, believe that reading can be a moral act. That by reading we get access to that truth, which some how makes us better human beings. I have often heard this argument and in my earlier years even used it to get people to read. I realised, even then, that I didn't entirely believe it as much as I would have liked to believe it. But the truth is, even if reading makes us better humans, there is no way to know. No data we can collect that can convince us, through logic — ah, logic — that reading makes us kinder, better. And in the absence of logic, we get lofty rhetoric.

When trying to answer the question “What does Kurt Vonnegut’s great novel have to say to us?” he answers, “It tells us that most human beings are not so bad, except for the one who are, and that’s valuable information.” What does one do with such banal literary distillations? A cozy notion of truth that he is either unable or unwilling to get into the weeds of. It makes me think that Rushdie, the literary juggernaut, has nothing in particular to say, and so is flooding the market, riding his Best Of The Booker success. It’s disappointing, but based on the largely positive reviews it has augured, also disconcerting. It is as if people love the idea of truth so much, they forget to even ask what the fuck it even means.

Let me tell you a story.

Once upon a time, long long ago, before the dark age of kali, a sage invited his students for a meal. His students were from two warring clans, and he wanted to put them to test. Each student had plates of rice heaped in front of them. Before they began the meal, the sage said, “You may begin eating. But there is one condition. You cannot bend your elbow.” One group of his students stared at the food, bent to lick it, tried throwing balls of rice from their hands to their mouth, making a mess, and failing the test of the sage. The other group decided to feed each other, because then, one wouldn’t have to bend the elbow. This group passed the test — they were the Pandavas or the virtuous brothers in the Hindu epic Mahabharata. The others were the Kauravas, or the evil brothers who usurp the land of the Pandavas and incite the big war.

This story, which I read as a child in the illustrated Amar Chitra Katha, was about cohesion. If there was a “truth” to the story, it would have been that.

But then, recently, in my work with the mythologist Devdutt Pattanaik, he told me the same story, but suddenly the context had shifted. It was used to explain the origin of human beings, and the natural world. It goes something like this.

The creator Brahma invites all his children to a meal. When they were about to start eating, he says that they can begin, but must eat without bending their elbows. Some of them went on their knees, licking the food, and they became animals. Some of them refused to eat and they became stones and the inanimate natural world. Some of them recognized that they could feed each other without bending their elbows, in the hope that the other would feed them, and they became humans, the cornerstone of whom is the idea of exchange.

It is the same story, but it serves a different purpose based on which telling you subscribe to. Now tell me, how does truth figure in this? Is the truth about the story — which is the same— or about the purpose/moral of the story — which is different depending on which narration you choose?

My contention here is that telling stories in the belief that there is a seed of truth waiting to germinate through verbiage is futile. The pursuit for truth in art flattens the experience of art. The idea that looking at art, reading books, watching movies, makes you a better human disguises that primal gasp when we experience great, sublime art, with something more mundane, more literal, more articulate, but less worthy of articulation. Let art breathe. Let artists make. Let the revelers of art revel. Let it all mean nothing.

This brings me to a genre of writing that peddles in truth as currency. The personal essay.

Vulnerability

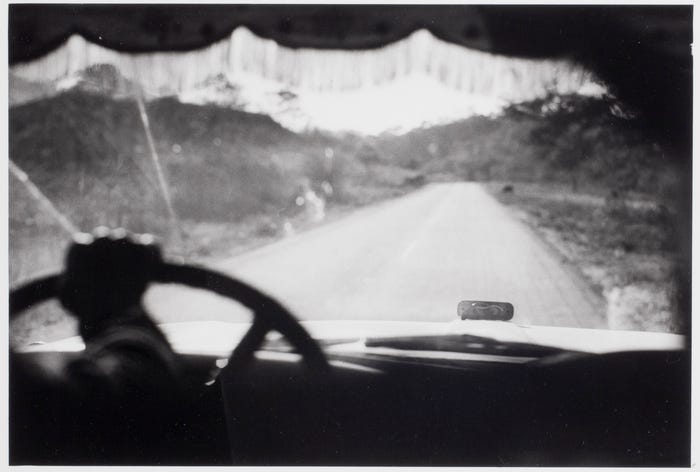

“Bombing” is when the skating board rumbles on the asphalt, “just getting past that point of any return”. One of the bombers who skates on the San Francisco hills noted that as you’re skating down in full speed you are definitely aware and cautious, but “a lot of it floats away magically”. One of them calls it a “violent ballet through the city”. I think of writing that is deeply personal as something like that. When I write a sentence so grotesquely personal, I love it, I keep it, knowing fully well that in my second draft I will erase it, because I have to erase it. Or if it is in a novel, I know I will add to it, morph it beyond recognition so that it is almost as if I erased it. That erasure is cowardice parading as editing, as often cowardice parades as editing (editing your own work, that is). The outcome is a work of art with less on the line.

There was a time when the New York Times refused to give its critics by-lines, and now its book critic talks about her child in parenthesis in the middle of a review. (I love Parul Sehgal’s reviews! Not everything I say should be read with a snark in its step) Its next logical iteration, the personal essays, what Laura Bennett lovingly calls the “first-person industrial complex”, is an understandable, sometimes even enjoyable, genre of writing. People love to talk about themselves, platform themselves, their lives distilled into profundity. I love doing it, though I am always grateful to have an editor who checks the indulgence.

But more recently, this past year, I have suddenly grown averse to pieces that center around the “I”. And I don’t mean anecdotes, but entire pieces built around one’s life, trying to explain it squeezing it for any semblance of morality. This feeling has been snowballing since I read Riz Ahmed’s tweet where he noted that you cannot be vulnerable if you are in control. The fundamental dissonance of most personal essays is that exactly — it attempts vulnerability with clawing control. I often think of what Parul Sehgal wrote about fiction — that it requires some measure of self-doubt which “forces [the writer] to double back on her sentences, unravel and knit them up again,” and to ask repeatedly:

Is this clear?

Is this true?

Is this enticing?

Here, of course, she doesn’t mean the romantic notion of truth. But that when sometimes in the “flow” writer’s churn out sentences that they don’t really mean, or that really doesn’t make sense, but it seems like it makes sense. A lot of contemporary poetry to me feels like this. I read it and I wonder, “You can’t possibly believe this.” It would be an articulate but empty take on identity or cinema or grief or literature. (It could be argued that perhaps my strong reaction against these works might be jealousy. That I can't write like this, whip up a fanbase. I have considered this. I don't think it is that, but really, who knows how this mind works?)

I was asked to write a review for a book and was encouraged to include my experience with queerness as part of it (70-30 was the ratio of review-personal, I was told). I was horrified but took the gig and ended up not writing anything about myself because it felt disingenuous. In one of the edit rounds I was asked if I had anything to add from my life. I said no. They were hoping for me to whip up a sentence that was designed to be quote-tweeted, something that could be snapped at, at a slam poetry night.

I often think about the following Knaussgaard quote, because, in my opinion, his autobiography — I am almost done with the first of 6 parts — bombs in the skating sense of the word. It rumbles so close to his life, unbothered by morals or profundities or even shame. He often noted that for literary freedom, you got to be ruthless. I never sense ruthlessness in these personal essays. It’s almost cloying, romantic. If one is afraid to dish on life as it is, why write about it at all? What do I do with these limp and lazy takes that become, in their worst avatar, celebrity autobiographies.

“The person you are in private doesn’t demand any insight, because there is no distance. No way in to traverse. Only yourself is what there is. But when you go on to another situation, there’s a distance, and the objectification turns the self into something else, while it remains the same. These tiny difference grow over time into conflicts — to an extent where the self can’t bear it without becoming dysfunctional. Because the self is also our frame of action. That makes it necessary to repress and forget but also to remember. Memories make up our own (non contradictory and manageable) narrative — maybe the most important part of our identity.” — Karl Ove Knausgaard

Later on he notes, “Writing about oneself is to some extent the opposite of insight because insight is directed inwards while writing about oneself is directed outwards. Yet both strive for intimacy and understanding.”

I want to end this piece with Kazuo Ishiguro (I have decided that this year I will read all his books and summon his tense simplicity in my writing). In his 2017 Nobel Lecture, he noted that at one point writing became “an urgent act of preservation”. I wondered what that meant, if it was one of the “romantic” things writers say to explain writing. I was wrong — it wasn’t. He explains that at the age of 5 he left Japan, and since then he was in Britain, writing British stories with British ideas, and then all of a sudden, one day, only Japanese stories leaked from him. He didn’t understand why.

“As I was growing up, long before I thought to create fictional worlds in prose, I was constructing in my mind a richly detailed place called Japan, a place to which I in some way belonged, from which I drew a certain sense of my identity and confidence. The fact that I never visited Japan in that time only served to make my vision more vivid and personal. Hence the need for preservation. For by the time I reached my mid-20s I was starting to accept that my Japan didn’t perhaps much correspond to a place I could go to on a plane. That the way of life of which my parents talked, that I remembered from my early childhood had largely vanished during the 1960s and 1970s. That in any case, the Japan that existed in my head might have always been an emotional construct put together by a child out of memory, imagination, and speculation.”

I like that level of clarity on oneself. On why one writes the way one does. Or why one digs the same theme again and again. It’s not as if there is one answer, but that there is some answer available.

I don’t know from where, but in one of the many loose sheets of paper floating on my desk I noted the following three questions. I like to use personal anecdotes to add colour to my writing. But one day when I am indulgent or coveted enough to write entire pieces about I-me-myself, I hope I keep these in mind.

This is the way it feels to me

Can you understand what I am saying?

Does it also feel this way for you?