On Violence In Movies

Radhe, Karnan, Asuran, Nayattu, all movies about and around violence can shed some light about how we craft concern and catharsis on screen

Last week I wrote about the Ramayana, and how the mythological pedestal is a death knell to to its literary qualities — to conceive of characters as gods or godly is a disservice to their capacity to reflect us, faults and functions, in them. Additionally, they are a lot less fun to read.

This week I watched quite a few films which in hindsight were all violent. The brilliant Nayattu on Netflix, the stunning but eventually diffuse Karnan on Amazon Prime, and the all round damp squib Radhe on Zee5. I wanted to initially just write about Radhe, because it was the tentpole theatrical film which ceded to streaming. Salman Khan’s inconsistent navels across his films’ CGI abs was a talking point. The 27 year age difference between him and his actress Disha Patani was another. But mostly critics, justifiably, just had fun in their reviews because who wants to critically engage with a headache? Turns out, I do.

Do subscribe, share, comment, write to me. Even if writing is lonely, its reception needn’t be so.

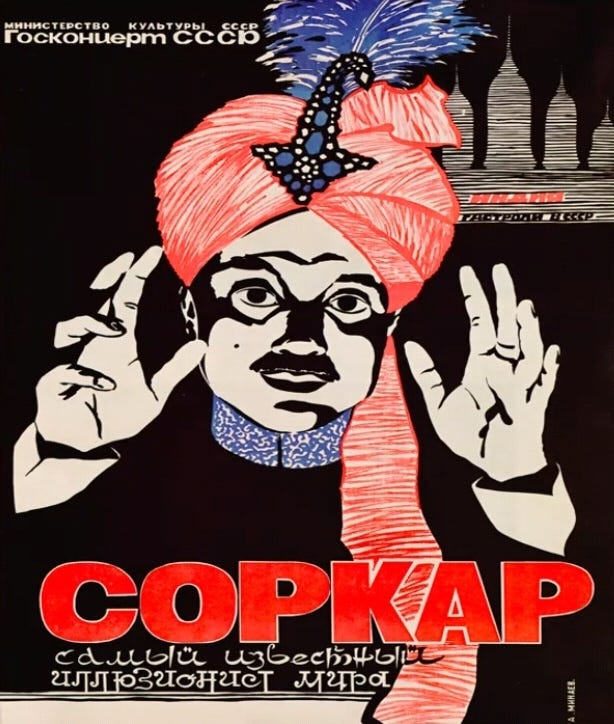

In 1956, the PC Sorcar, who called himself “the world’s greatest magician”, was on BBC. Live on air, he chopped his hypnotized assistant in half with a massive buzz saw which made a frightening bone-crunching roar. But before he could stitch her back together — the “third act” of any magic performance — he was cut short; the presenter of the show stepped in front of the camera and announced the end of the program.

The phone lines at the studio immediately jammed, with concerned callers worried that they had just witnessed a murder on live television. The following day’s newspapers reported this alarm on their front pages, "Sawing Sorcar alarms viewers".

Nothing happened, though. The official explanation was that Sorcar’s act had gone over-time. But many who were following Sorcar’s rise knew that he was playing the new media landscape to his advantage — using the modern gifts of editing, camera angles, the limits of live television to reach a wide audience, and violence to shock a wider audience into concern. It worked. His season at London’s Duke Of York theater sold out.

If the trick had instead been to disappear the assistant, the reaction, I assume, wouldn’t have been this strong. Violence is obviously existential — it can end one’s life, and you can see the life draining with the blood. The reaction to violence, is thus understandably pungent, primal, and emotional. But when this life becomes symbolic — like a hero who inheres all the good of society, or the villain who inheres all the bad of society, or the Robinhood who inheres the bad of society for the good of it — the end of that life also becomes symbolic. So the death of hero becomes the death of goodness. The death of the villain is the end of all that is bad among us. It is why filmmakers must tread lightly when ending issue based movies on a note of Happily Ever After. Because to show the consummate victory of the symbol, while the reality of which it is symbolic is still languishing, is to celebrate premature victory.

Nonetheless, violence provides us a template to exhibit concern and experience catharsis, at least in the movies. It elevates the value of human life by bringing it to the brink of extinction.

Violence In Cinema

As a child, I never understood the allure of action movies, or even the violent video games for that matter. In the video games, the violence seemed unearned — who are these pixels you are turning to dust, what did they do to deserve this? The response I would get “It’s fun” scared me a little at first, and then a lot as I grew up, meeting people who would hammer neighbourhood squirrels “just for fun”. It’s not the same thing I know, but is it not similar?

In the movies, however, the violence I was seeing seemed gratuitous, in service of something larger than I couldn’t comprehend then — herohood. I would watch most of these movies of roaring heroes on television which, because of mom’s strict instructions, I had to sit far away from lest it spoil my eyes. I didn’t realize that these were moments meant to be communally enjoyed with your frame engulfed by a giant screen. The house-help whom I grew very close to would watch every Rajnikanth movies again and again till the tape scratched, and when I visited her in Chennai, she took me to a theater to see one of his films. I don’t remember the movie. I remember the celebration.

With Hindi movies I was still unsure. It was in Tamil movies where I first found an articulation of violence which I understood, perhaps even championed over time. Like the audience of Sorcar’s magic trick, the response violence on the violated can elicit at first is concern. This is done by carefully amping up the moment of violence — when the sledgehammer hits Asin in Ghajini, when Ambi is kicked around by everyone in Anniyan, when the fists pummel in a kabaddi match in Gilli, when the burnt bodies are shown in Asuran. My blood boiled. How could this happen to someone? The concern slowly builds into a demand for justice.

But concern, at least in cinema if not life, must yield to catharsis. And so the hero strikes, and we applaud. But to elicit catharsis, concern must be established. A lot of the Hindi films don’t do that well, and instead, as in Rohit Shetty’s movies, the action sequences become an expression of creativity. It’s no longer important to see that the hero pummels the villain, it is important how he does it — if it’s walking out of a speeding car to spray bullets as the car swerves, if it’s a slow-motion kick to a villain side-kick, who in its impact sweeps across the floor to crash into a popcorn cart, if it’s the droplets of water from wet cloth which squeeze out of it as it is wrung around the neck of the villain. These are action sequences without emotion, the kinds that critic Pauline Kael worried about all the way back in 1974. Which makes me ask – should violence be emotional?

“It’s the emotionlessness of so many violent movies that I’m becoming anxious about, not the rare violent movies (Bonnie and Clyde, The Godfather, Mean Streets) that make us care about the characters and what happens to them. A violent movie that intensifies our experience of violence is very different from a movie in which acts of violence are perfunctory. I’m only guessing, and maybe this emotionlessness means little, but, if I can trust my instincts at all, there’s something deeply wrong about anyone’s taking for granted the dissociation that this carnage without emotion represents. Sitting in the theater, you feel you’re being drawn into a spreading nervous breakdown. It’s as if pain and pleasure, belief and disbelief had got all smudged together, and the movies had become some schizzy form of put-on.” — from “Killing Time,” a review of Clint Eastwood’s Magnum Force

Asuran, Karnan

I want to talk about Asuran and Karnan together, because here is a comparison that yields interesting results. Both are about caste-based violence, both have Dhanush, both are rousing films, and both are on Amazon Prime.

While Karnan is more emphatic about violence towards a community, Asuran is emphatic about violence towards a family. So the first film has a broader mandate and diffused impact, which explains the constant need to have those top shots showing that what is at stake is not the existence of a family, but an entire village. Dhanush’s establishing hero moment in Karnan is the slashing of the fish mid-air in front of the entire village, while in Asuran it is at night, with his two sons, as he is trying to kill a wild boar that is trampling the crops. The violation in Asuram is thus more contained and personal — the murder of his son, the burning of his lover. The violation in Karnan, however, is larger — it is about a woman from his village being humiliated, is about the bus not stopping at his village, is about his kabaddi team being cheated off points. The violations and concerns that simmer and accumulate are larger and so the final set piece is also larger — with a top-shot of the whole village charging at the police. The interval moment too is striking. It’s him battering a bus into shards, the bus being, as Baradwaj Rangan noted in his review, symbolic of all the violence and indifference inflicted on his community and his village.

While in Asuran both the interval and final fight scenes just pit Dhanush against the villainous crowd. Right before the interval, he is even apologizing to members of his community that the violence that his family is fighting against is affecting those of his near and dear.

Even the final shot of the films make clear their intention — with Dhanush staring at his family in Asuran before the legal judgment against him is even made, and with Dhanush dancing with the village in front of the finished memorial mural in Karnan, after his being released from jail.

It's also important to notice how government institutions are woven into each story. In Karnan, where the whole village decides to galvanize, the villain cannot be a person. It has to be something just as powerful in a collective and thus you have the entire police force as the villain here. In Asuran, where the ones fighting for justice is one family, the police are merely complicit, and not the main aggravators of violence. Because you don't need an entire institution to stand up against one family. The disproportion would be too stark, narratively speaking. It's also why in Asuran the hero keeps looking towards the system to help him – the local panchayat, the local police, the local courts. In Karnan, it is a wholesale renunciation of the rotten system. The point is thus more poignant and also more palpable. Because there is no one to look towards but one's kith and kin.

But here is the drawback of Karnan. When you aggregate the violence over an entire community, it is just as important to aggregate catharsis over it. In Karnan, the final battle is between Dhanush who represents his community, and the superintendent of police, who represents the proactive and complicit violence of that institution. They are both locked inside a hut. The killing is done, but the satisfaction isn’t there because all of that community humiliation, violence, and murder ends in solitary death. Asuran has this down pat, because when the good guys are humiliated in public, the revenge against the bad guys are also in full public view. Cinematic justice must be proportionate to the cinematic injustice initially meted out. At least for these big masala movies.

This is why everyone prefers Mari Selvaraj’s first film Pariyerum Perumal to his second, Karnan. The first film was entirely about one person and through his tribulations the larger systemic injustice is laid bare. The concern and catharsis here is concentrated, and the pay-off just as sumptuous. Very few films effectively galvanize an entire community as the violated. The few that come to mind are the women in Lajja, and the youth in Rang De Basanti. Perhaps Trial Of Chicago 7?

Editing Violence

So much of the violence of a film is located in its sound-design. In the very first scene of Radhe, for example, when the villain clubs a man’s skull, the camera pans skywards as the sound of a skull smashed is made prominent. The idea is to spare us the gruesome visuals at the very beginning but to make the point nonetheless — that this villain lacks goodness, and can’t be redeemed

This is also a recognition in this movie of what “too much violence” might entail. So instead of having long shots where Salman Khan batters and bruises the villain’s henchmen, they just show a shot with all of them hanging from ropes on the ceiling or fallen on the floor, defeated. How it happened isn’t instructive here. That it happened is enough. This makes sense for another reason. Radhe is so wildly pointless in trying to establish who the violence is directed towards, often you are not sure why the villains (yes, plural) are the villains. Since intent is not established, to have long drawn fight sequences would be that much more tiring to sit through because you are not rooting for anything, anyone.

In the climax of the film though, the hero smashes the head of the main villain with a metal pipe, but the visuals are carefully stitched to give the impression of violence without its realism — there is a wide-shot of the pipe about to strike the skull, followed by a close-shot of the pipe actually meeting the skull in a muted fashion. There is no visual nausea because you are not seeing it play out in one shot, looking for lurking visual tricks they used to make it feel and look real. This is very common in films — to show the violence inflicted by the hero with restraint through the edits.

In Karnan’s climax, for example, when Dhanush hits the evil officer with the sharp end of a valakku, the shot of him whacking the man is followed by him falling down. The strike is never shown in gruesome close up. I see this across a lot of movies where the violence of the violated isn’t as pronounced. In Asuran when the spear grazes the hand of the hero you can see a speck of flesh flying, with blood clotting immediately. When the spear is plunged it’s shown clearly. But when the hero whacks the lot, one after the other, it isn’t blood that is foregrounded as much as macho-dom. You never want to look away from the screen when the hero is smashing, but the edit patterns conspire to conjure disgust every time the hero is hurt. The gruesomeness is muted when the villain is struck, so much so that when the final spear attack is waged against the main villain, the screen blurs for a second, and then you see him on his knees.

But beyond the scripting of a violent scene, it is also interesting to note the plotting towards a violent altercation. There is often a logic to it, which is best showcased in Nayattu. Where small details, small skirmishes, small irritants build up to a sudden eruption that you don't see coming. The distance between the cause of violence and the act of violence is so negligible it almost bleeds and becomes one. This, as opposed to a film like Karnan where violence is always lurking palpably, makes for a less tense viewing because you're not waiting for the strike to happen, waiting for that moment when the state fulfills its duty to instigate. Because ultimately violence needs a reason. Even if it's airy, incoherent, the pretense of it is enough to mount anger as virtuous, necessary, even respectable.

This week I published quite a few articles. I started writing for First Post for whom I reviewed Ammonite and Halston. At Film Companion, I contributed to the much discussed list of the 30 most beautiful Hindi movies of all time. Some asked what criteria we used to decide on beauty. What do you say to that? I also reviewed Minari and Girish Karnad's warm and messy memoir. He wrote it in Kannada in 2011. He passed away in 2019. It's translated to English in 2021.

I was also interviewed by Music Journalism, who kindly plugged my piece, An Oral History Of O Sanam.

Just awed by the detail amidst your fluid narrative Pratyush! The part on how the edits play a significant role in the stunt scenes - something I intutively understood - you put words to it. brilliant post - congratulations on the other writings as well::) !