In episode 8 of Marvel’s WandaVision, a line of striking clarity is delivered, “What is grief if not love persevering?” Within minutes all of Twitter knew it, and within hours it was meme-d out of its original meaning. The internet kills everything of value. Which perhaps explains why sometimes we feel the urge to hold something we love so close—the urge to not share it becomes part of the urge to preserve it, without exposing it to the vagaries of public opinion uttered in private confines (Twitter), and the meme industrial complex.

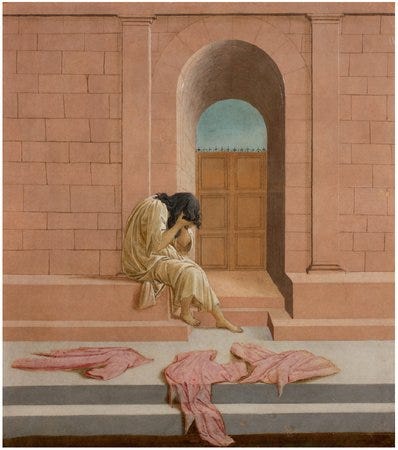

By the time I got to the eighth episode, both the beauty and banality of that line was stretched and strained. It had no impact on me. So instead of feeling through the lines, it was easier to philosophize through them. WandaVision is a cypher, using formats of undeniable charm and popularity—sitcom, mockumentary, superhero—to deliver an undeniably prescient message. That grief is singular, and the process of grieving uncharacteristic of yourself, and inward looking in ways that might make you indulgent at best, and villainous at worst.

The Capaciousness Of Grief

In the film The Namesake Aashima, played by Tabu, is confronted by the death of loved ones on two occasions—her father, and her husband. Both scenes, for me, stuck out as shrill and choreographed. Aashima is seen as a level-headed character who recognizes the pain in reaching beyond her circumstances, content with finding small joys within the confines of her life. There is an immediacy to her—where she recognizes the importance of the present, and the futility of complaining to people who can’t do anything about changing it. Like the letters she writes to her parents after arriving in snow-clad America, refusing to speak of the cold, walled-in world that she finds herself isolated in, a far cry from her life in India where houses and nosy neighbours bled into one another. What would her parents do knowing of her sadness except worry themselves sick?

My criticism of the scenes were how their shrillness seemed radically uncharacteristic of Ashima who graciously pulls herself out of focus when she isn’t needed. But what if, like most people, Ashima in the face of grief finds herself acting in ways she would never have imagined. What if grief makes us do, say, and be things we find ourselves incapable of doing, saying, and being otherwise; the specious quality of grieving where you morph into anything, even a contradiction of your own self. You thought you would weep buckets but your eyes are dry as an itch. You thought you would be unmoved but you are suddenly incapable of getting out of bed. It’s grief—it makes Instagram into a memorial giving words a power they never had before. It makes quiet people like Aashima a shrill center of attention.

When, in Disney+’s show WandaVision Wanda, a witch from Eastern Europe, loses her father and then her brother, she turns for consolation to Vision, an android, who tells her, “What is grief if not love persevering?” But when, after falling in love with Vision, she then loses him too, whom does she turn to? Whom can she turn to?

Often it isn’t the words themselves but the one delivering it that matters. Wanda doesn’t have that and in a moment of deep, isolated grief, she subconsciously brings him back to life. But this is not just illegal (against the Sokovian legal code) but also immoral (going against Vision’s will to be resuscitated).

She inheres what Siddharth Dhanvant Shanghvi noted in his monograph on grief, Loss, “[P]resence is the only gift we can give one another… all healing is tentative grace.” She invokes his presence, wiping his memory clean of everything, and moves with him to a suburbia in New Jersey in the 50s living life as characters in a sitcom. This, to her, was not a tentative grace but hopefully a permanent stage.

The Morality Of Grieving

Their life in New Jersey plays out through sitcoms, in black and white. The Dick Van Dyke show is the aesthetic touchstone, and towards the end of the show we realize that this is not incidental—as a child the illegal stash of Dick Van Dyke episodes were the centerpiece around which her family comforted themselves in the middle of war-struck Soviet Sokovia that embargoed any seepage of American imagination. It was while watching the show that the bombs exploded, killing her parents. In this moment of grief too, understandably, she manifests this childhood comfort but with her lover Vision. They are happy in the domestic sense—where bliss is a kiss at night before you melt into your lover’s arms while the television drones on.

But like with every sitcom, there is a cardboard setup but there are also extras, and there is a writer, a director, a show-runner. Soon, the moral implications of this manifesting of childhood comforts has to be confronted. Who are these people who pop into their lives—the nosy neighbour, the spirited neighbour, the excitable colleague? It isn’t like the first few episodes drenched in shenanigans “more silly that scary” are bereft of tension. The colour red begins to appear almost as an invasion. Odd lines are spoken and snapped out of. It soon becomes clear that Wanda, the showrunner, is not entirely in control of her own production.

Wanda is brought face to face with the moral implications of her grief—she converted an entire modern day suburb in New Jersey into a 1950s set, each character in the sitcom is a modern day living person held hostage in this sitcom—their minds controlled by Wanda, giving their captivity a Descartes-esque quality. If it is the mind that is held hostage and not the body, thus one is unaware of being held hostage because of the illusion of freedom, is one really held hostage? Plato’s Cave comes to mind when seeing these characters mill about in the 1950s languor of harsh lighting.

This does two things. The implications of kidnapping are muted because people are not physically revolting to it. (Like how we treat mental illness as somewhat inferior to physical illness, because of the illusion of the mind as self-curing and sentient.) Thus secondly, in order to be confronted by the violence of this situation Wanda needs to be brought face to face with the people whose mind she colonized. It is finally Agatha, the nosy neighbour who is actually a centuries old witch with dubious morals, but for me not necessarily evil, who does this—for a moment she brings back the modern day consciousness of all the people in the suburb who flood towards Wanda begging her to return them to their life as it was. It’s a chilling moment where you realize that the curated comfort is actually a glazed prison of the mind.

“As WandaVision progresses, it can be read two ways. The show does champion entertainment as a safe and welcoming space for those looking for an escape, but it also acts as a cautionary tale for those who employ it as an unhealthy coping mechanism. Sure, the movies will help you take your mind off your problems for a while, but they won’t fix them permanently, it underlines time and time again…As the audience looks to escape their reality by tuning into television shows, Wanda rewrites the fabric of her reality by living in one.” — Gayle Sequeira

It isn’t like Wanda is entirely unaware of her capacity to control people. It is true she created this world subconsciously in a roar of grief that emanates outward converting every place and person her voice touches into a 1950s set-piece. It is also true that Wanda isn’t entirely sure what the limits of her powers are, because where there are powers, there will be ifs and buts. Yet, she understands that she wields some power over the lives of people. In an Episode 5 Vision, who is suddenly recognizing the violence of this world, confronts her, “You can’t control me the way you control them.” She replies, “Can’t I?”, and rolls the bumbling end credits to coat this scary with silly. But now suddenly, it is the scary that strikes.

The laughter track’s narrative function too morphs over the course of the episodes to mirror where we are with the story. Initially, it elevates the chuckle in your head and a smile in your lips to a full throated guzzle that comes at you and not from you, even if the joke isn’t deserving, especially if it isn’t. (The laughter track is the definitive attempt to blur the distinction between something coming at you versus something coming from you, a version of mind controlling, a subtler Wanda.) But later on, as the darkness of this world becomes clear, it carries a discomfort, like laughing through a tense dinner table by holding onto dregs of humour.

The Genre Of Grief

Emma Copley Eisenberg writes about revenge, “[It] is the place the fracturing mind goes when it is trying to stay whole. That is the paradox of it, because revenge often means doing—even justified and righteous things—from which it is very unlikely you will return whole.”

If you replace the idea of revenge with the idea of grief as experienced by Wanda, it is not hard to see how similar they are. Grieving for Wanda takes the curious shape of revenge against circumstances, time, and even truth. (The children she gave birth to in the Hex, the Sitcom world, what happens to them? What happens to things said and done in the Hex? Consequences for actions committed within it?)

The other part that likens the two is how, at the end, when the grieving as revenge is done, Wanda isn’t exorcised of the pain of loss. She may now have exacerbated it with the guilt of holding so many minds hostage. This, in the show, is a lovely touch because often grief is seen as a frontier to be conquered. Wanda notes the repetitive nature of it, like waves crashing — initially stronger, and the hope is, over time, weaker waves, but the waves will crash, and maybe in the midst unsuspecting mild splashes, there might lurk a Tsunami. To escape these tidal waves she creates a fiction. But the limits of fiction can’t be ignored.

To escape grief, that is a genre too. Pieces Of A Woman comes closest to providing the loop of closure—where it begins with the act that will cause grief, the miscarriage, and ends with the act that renounces grief, the monologue in front of the court. Sometimes, as with After Life grieving is about the cantankerous, almost shrill, and permanent aftermath. Sometimes, as with Fleabag or Zoey’s Extraordinary Playlist, it is about the permanent lingering background noise that grief becomes.

WandaVision, however, by allying itself with revenge doesn’t dwell too much on the grieving, or even the act that caused grief—Vision’s death is shown in a 2 second flash clip in the recap.

This urge to bring back people from the dead is very common. After all, it is hard to believe that life is an exercise of falling together and apart till there is nothing to fall together and apart with. In the Hindu mythology that I was fed copiously, this is a bit of subculture—dead people being brought back. The most extreme of this has got to do with my surname Parasuraman which is named after the mythical figure of Parashurama. His father, the saint Jamadagni, realized that his wife, Renuka, stared at a beautiful man for long enough to harbour lust in her heart and so told his sons to cut off her head. Four of the sons refused because Renuka is their mother. In anger, the father castrated them. The youngest, Parashurama, agreed to do this, and willingly cut his mother’s head off. His father, pleased, grants him a boon. He uses this moment to bring his mother back to life.

A less violent story involves Savitri who follows the god of death, Yama, who has her husband Satyavan in tow. Her persistence annoys him, and finally Yama relents to her persuasive wit. Satyavan is brought back to life. Death here is as simple as being being in another country, a tangible border away.

It is so easy to believe that all it takes to bring a lover back to life is persuasive wit. The first book I ever read, RK Narayan’s The English Teacher is about a man attempting to get over the death of his wife, by seeing an apparition of her every dusk at the fields. It's how for the longest time I thought grieving works — hallucinations.

One thing that grief can do, is give perspective to look at things anew—to structurally infuse appreciation, for even the most banal things, into one’s life. WandaVision takes this and makes it one with its storytelling. The show takes four of the things we either ignore or now fast forward through — advertisements, recaps, opening and end credits — and makes us now pay attention to it for dregs of art and context. Small details not shown in previous episodes pop up in the recaps, the ads prop the sitcom energy with Easter eggs that were lost on me but Marvel fans got, and sudden scenes erupt after the credits roll.

But this was precisely where I found the show questionable because it was doing so many things differently, that the novelty of it became indistinguishable from its quality. That it’s new, something we haven’t seen before, and is engaging at it is enough to call it amazing. It’s always tricky to think critically about novel works of art. Do we love it because it’s new or because it’s great? Can newness be considered greatness—the vanguard being also the threshold for good art?