On Political Art

On white photographers, Viola Davis' popping melanin, and Anubhav Sinha's shrill political films

I have never believed that art can make one radically reconsider one’s life or opinions. (I often cite Camus’ The Stranger as the reason I pirouetted away from Economics towards writing, leaving my job etc., but the more I think about it, the more I feel that I’m probably giving the book more credit than it deserves, as the decision was, probably, already there in my head. If instead of Camus, I was reading a Sydney Sheldon or an RK Narayan I would have probably done the same thing i.e. left my job. But then again, there’s no way to know.) Perhaps this comes from how I see art these days as vessels that must hold us and our fluid, shapeless desires, as opposed to say … a fridge or a fire that will jolt us to reconsider our potential- to be both vapour and ice.

To comfort the discomforted and to discomfort the comforted- this Banksy quote is often used to describe the role of art; Banksy who shreds and graffitis, as the world collectively drops their jaws. I don’t think it’s that simple, though I do wish it was.

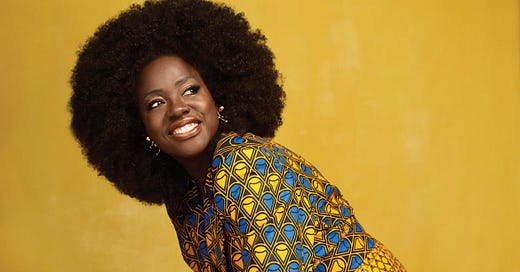

Nzinga Simmons, an Atlanta based art history scholar was on the Modern Art Notes podcast last week discussing Vanity Fair’s latest cover- a teal tinted portrait painting of Breonna Taylor by Amy Sheralds, famous for her portraits of Michelle and Barack Obama at the National Portrait Gallery. It was hailed as a big moment. Just the previous month Vanity Fair, described by host Tyler Green as “idealized popular Americannah”, had its first cover, that of Viola Davis, shot by a black photographer- Dario Calmese. This was the mainstreaming-without-marginalizing of black-culture that most black people hoped and are still fighting for.

Why is it that a black photographer photographing a black subject is important? Representation, sure. But there’s also an aesthetic reason. That same month Vogue’s cover story was of Simone Biles, the black Olympic Gymnast, shot by one of my favourites Annie Leibovitz. But Biles’ cover story quickly got pulled up by Twitter for doing some rather odd things with her skin tone. Leibovitz, a white woman, has often in the past not known how to light skin that is darker than the ones she has often worked with. And despite her brilliance in composition, this lacking shows. There is something to be said about the act of inserting yourself into a context someone else knows and thus can photograph/write about/film/articulate better than you could. Kaitlyn Grenidge’s tweet showed up on my timeline as I was writing this, like clockwork.

If you are writing a marginalized character whose identity you do not share...can you imagine your way into that character through their joy and not their imagined trauma? [A]nd can you recognize that joy looks different than how you may categorize it?

So that was one joy- of Vanity Fair’s first black cover photographer. It reminded me of Brian Horton, a queer theorist I was speaking to for research on a project. He was working on his PhD thesis No Nanga Naach, No Flamboyance, and he said “What do queer people do when they are not suffering?” His aim was to look at other ways of defining queerness- as an identity not just of doom and gloom, something most non-queers, even allies, fail to see beyond.

Then there is Nzinga Simmons, and Breonna Taylor. Simmons said something that struck me and has since been simmering in my head.

Art can take us to a liminal space and then back to reality to affect change.

Note the word can, as opposed to should. Because art doesn’t always need to have or make a point. It could be Vaughner’s idea of art being the only place where one can experience pure happiness, pure joy, pure love. Or it could be Victor Vasarely’s op-art I wrote about last week that is merely made to make you feel dizzy.

Nzinga said the quote in reference to the criticisms the cover was getting from the community. That this cover image instead placed Taylor, killed in a police shooting for no crime or rhyme or reason, in this idyllic imaginative landscape was a bit disappointing. It didn’t rouse action, merely joy, and of what use is joy in a joyless market where we purchase justice only through despair. The colour, Nzinga mockingly noted, was based on Taylor’s birth stone. This isn’t an image of Taylor that existed or was widely circulated for easy cross-referencing. She is painted wearing an engagement ring- her boyfriend was about to propose to her, before the shooting marred both the plans and her. In some sense this was Taylor with no signs of strain, “A Beautiful Life”, as the headline suggested.

The criticism, and this is a very valid criticism for every work of political art, is that it makes a statement without doing much more than that. It merely makes visible the issue, but the question then stands: What does visibility actually do?

This ties in to a conversation we often have in India about political cinema. The director Anubhav Sinha is brought up, his Mulk about the Hindu-Muslim schism, his Article 15 about casteism, and his Thappad about domestic abuse. I have watched only the latter two, and that’s put me off his work for a while. It’s progressive, but it’s also shrill, and while dealing with an uncomfortable issue, ultimately it leaves you comforted. This kind of cinema never worked for me, because in my head I am often wondering about who this film will move, and to do what? These are issues that are bloodletting and I couldn’t fathom why I should walk out of the theater feeling satisfied after watching casteism raise its bloody hood and strike for two hours on screen.

The only good example of political art in Hindi Cinema I can conjure up is Rang De Basanti, a rousing, effective, almost nihilistic film. (Pariyerum Perumal is that caste-based political film I was looking for.) There is a candelight vigil scene in the movie that inspired people in Delhi to do a similar thing for the Jessica Lal murder case. Here’s an example of art leaking into life. (not changing, I still stand my ground) So perhaps, here, I might want to make a distinction between political cinema that comforts into knowledge, and political cinema that discomforts into action. I am a fan of the latter, though I don’t mind the former if it’s… less self-righteous. (I am thinking of the episode on How To Get Away With Murder about the death row to the black man for a crime he did not even commit. It’s effective, makes the point, but doesn’t ask for a pat on the back.)

Let me briefly talk about queer cinema in India before signing off. I just endured the worst-best 1998 film Gunda for a piece. There’s a flaming-queen character, Chuttiya (hard T), whose macho, loving brother imports viagra pills from London so he can get it hard and have sex with women. It’s bizarre enough for you to just… not take offence. It’s beyond the “fields of right and wrong” as a romanticized translation of Rumi would put it. But there are some movies which have under that garb of representation made a rather stereotyped point. Love is love, and gay love is OTT. The argument made is that we finally have a mainstream gay film, even if it just camp and ramp. As Anupama Chopra, my current boss, wrote in an LA Times pieces “Laughing about it is the first step toward more textured and nuanced characters.” (I don’t agree entirely, though I loved Dostana the film she was referencing, which sent queer people in a tizzy because of its blaring stereotypes. I didn’t see it as more than a film that, despite its problems, entertained. But there have been radical reactions. Harish Iyer, the queer activist used it to come out to his sister. Many others had to be part of family conversations demeaning the community, as powdered and painted, using the film. It’s a mixed bag.) Parmesh said it best in his book Queeristan

To me, Dostana’s subtext opens up possibilities of re-imagining family acceptance- flawed possibilities, gendered possibilities, but possibilities nonetheless.

So the point then becomes about art opening up possibilities. Good art can show these possibilities, but good political art, should show the anguish that the fight for these possibilities will entail; to not be happy about eventual justice, but to be angry about impending justice.

I must note that this are my opinions now, in self-imposed isolation, craving feeling of any kind. (The most euphoria I feel is when I do eye exercises in my terrace, forcefully keeping my eyes open as I stare up at the sky, and it waters, it burns, but it’s a pleasant burn. Also this Hoffman compilation.)

Perhaps my opinions will change, but the questions will still stand: What does one do with knowledge of pain? What does one do with visibility? What does one do on information one lacks the conviction to act upon?

I guess the questions will rage till the human rages, but in the interim, we must, as Marc Cousins paraphrased Robert Bresson, “try to show that which without you might never be seen.”

If you like what you read, tell others. If you don’t, tell me.