On Satyajit Ray And Guided Meditation

Ray's Aparajito moves from Kashi to Calcutta. Six years ago I took the opposite journey.

I realized this weekend that watching Satyajit Ray’s films is an act of guided meditation. The details, swamped in lush lighting and careful articulation of space, draw you in so wholly, so calmly, so steadily. I am not using the phrase “guided meditation” lightly; it is not a ponderous label to give any good, beautiful film. It is about forgetting where you are, and believing that you exist in this other universe, ultimately bringing you back to this world, calmer, and more perceptive. (This, despite watching Ray’s movies on my smartphone with a fraying protective cover, dotted with sand from Juhu beach from months ago, with heavy Diwali crackers bursting outside.)

Guided meditation as an idea entered my mind when I told my friend of my sudden urge to want to have my own kids after seeing the latest children’s book collection from an Indian publisher, Juggernaut. She told me (correctly but unconvincingly), “You don’t need kids to read kid’s stories.”

But then, she told me about a podcast where a 5-year-old child reads his meditation, and she called it “the best guided meditation [she] ever heard. He told [her] to go to the moon and look down into [her] backyard. So much cooler than “bring awareness to your toes”” So, now kids are back on the table. (Side note: It’s a very ASMR episode about insomnia and the pandemic, with a very nice lullaby, and glow-in-the-dark PJs. The kid’s meditation begins around 27:00.)

In Satyajit Ray’s Aparajito (1956), the second in Ray’s Apu trilogy, the main character, Apu grows up in his travels between Kashi and Calcutta. In Kashi he is a child, unmoored by adult existential worries, and in Calcutta he is a college student making ends meet, figuring out his affections for his mother- an adult admixture of gratitude and guilt. His mother, a widow, lies in the village, alone and growing frail with age, while he eschews the life she imagined for him- of a priest - for that of labour and academe.

Now, let me make this all about me.

When Apu leaves his village for Calcutta, his village-school headmaster gives him a globe as a parting gift. Having left the echoes of a parochial life of Kashi and now his village, he is onto Calcutta.

Years ago I took the reverse journey from Kolkata (then Calcutta) to Varanasi (then Kashi). It was the first trip I took by myself within India, and I don’t know how I managed it, without internet, or a functional phone. I used an unpaid internship in Kolkata as an excuse to be there. (This was when I was absolutely certain I could plot the demand and supply of sex-work on a graph, and decided to spend my summer in Kolkata in a dusty library of a women’s collective, a UNICEF office, and a law college, all of which served only to muddy my initial unanswered research question. This was my first year at University studying Economics rigorously. Three years later, when I was teaching the first year kids the same subject, I warned them against my naivete- that there has never been evidence that the demand curve is downward sloping, or the supply curve is upward sloping; it is just theory we have assumed as fact.)

I was to travel from Kolkata to Varanasi with a friend, and from there to Nasik for the Kumbh Mela. But the day before our train to Varanasi, my friend’s grandfather passed away and he couldn’t come with me for he had funereal duties. I stared at the Rasmalai Smoothie poster at the train station’s Cafe Coffee Day, hoping he would materialize as the train was leaving the platform, and say, “So Grandfather is alive again, and our trip is on!” Alas, no such thing happened and I met some kind people on the train who protected me from the wild hawkers and loud auto-drivers at the Varanasi train station. (This was also where I met a man who described Mumbai as a “jalti hui kati patang”, a cut kite on fire. When I would move to Mumbai years later it was this that I kept in mind.)

The Kumbh Mela part of the itinerary was axed because father would not have me go there by myself. It remains to be experienced and articulated.

As I left Kolkata, the landlady of the house I was staying in gave me a coconut, and I was confused- I took her blessings, her coconut, and her dazed exasperation at this tenant who bugged the fuck out of her- for sugar, for dinner, and by entertaining people who would laugh loudly. I googled the ritual of coconut-giving and apparently I was supposed to break the coconut before starting off the journey as a sign of good luck. But the floor tiles were so beautiful and fragile that I decided I would break it outside on the road, while hailing a yellow cab, but then forgot about it, the coconut lodged in a side pocket on my carry-on.

As Apu came to Kolkata with a globe, I left it with a globular, un-smashed, husky coconut. Neither of our journeys were radical as much as necessary. For Apu to believe that he could partake in the grinding, and quicksand world out there. For me, it wasn’t as cinematic, but there was a kernel of self-doubt that I wanted to erase. I watched Aparajito on festivalscope this weekend, and that site doesn’t allow screenshots that I wanted to use for this piece. I will have those images embedded in my memory till I forget them.

Instead, I’ll offer photographs I had taken of Varanasi. I lived in a ramshackle by a ghat, mice running about my bed, and cows dropping dung shamelessly. I began my till-this-day lasting affair with kulfi from the nosy seller outside. I spent each of my four days there walking all the 88 ghats. It would take 4 hours one-way and 4 hours the other-way. I would time the walk so, on my way back, I could be at Dashashwamedh Ghat by 6 p.m. for the Ganga Aarti that would start around 6:45 p.m, with the smell of sweaty musk and burnt flesh I had acquired from walking through Manikarnika Ghat where they burnt the dead bodies. On dry days I would take my camera, and on moist ones I would wrap fifty rupees in a plastic bag and shove it into my pocket as I walked with an umbrella that would usually be ineffective against the directionless rain. I fell sick the morning I wanted to bathe in the Ganges, so that too remains to be experienced and articulated.

Now, looking back at these photos, I think of me six years ago, and I think of Satyajit Ray sixty years ago on the same ghats, (I am not making an equivalence- I might be vain, but I am not delusional) trying to find a story of escape. Ray making his characters flee these stepped banks of the Ganga for the village in search of security. In Aparajito when the mother takes Apu from Kashi/Varanasi back to the village, the industrial rattling of the train soon becomes overpowered by Ravi Shankar’s sitar music as the landscape changes from the city to the village- the romance of village life ossified in the background music. Apu would leave the village anyways, privileging the uncontained universe of the city for the contained comfort of the village. He won’t always be happy, but the point was never to be happy, but to be hungry.

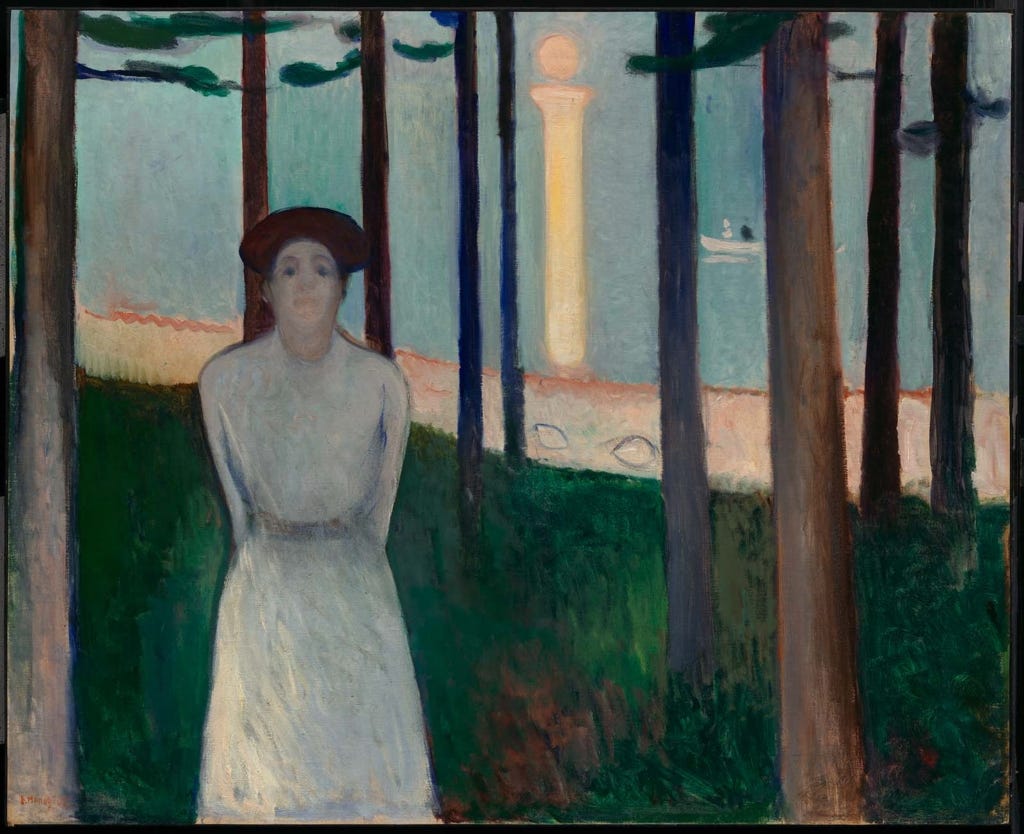

The last image reminds me of Edvard Munch’s ‘Summer Night’s Dream’ (1893) in the way the Sun here and Moon there make a reflection that looks like a pillar.

This was such a honest and heartwarming read. Thank you for sharing! Kolkata and Kashi remain two cities close to my heart for chaotic reasons, and I grew up watching Satyajit Ray movies with my grandmother. so I really enjoyed this post. :)