On Art Post-Disaster, Post-Pandemic, Post-Languishing

What do we do with art during disaster? What happens to art when the disaster subsides?

By the time you read this, the Oscars would have been announced. If Nomadland wins, here is your guide to the movie, the journalistic account it is based on, and what it says about a disappearing middle-class. This week’s piece isn’t empty musings of despondency, though strains of it will emerge — I try to look back at another moment of sheer disaster, World War 2, and see what came of it artistically. I am moved by a conviction that when all the dust is settled, something new, feral, angsty, and rousing will be made. Do subscribe, share, comment. Write to me if you are so moved. Take care, nonetheless.

In April 1945, at the Lefevre Gallery in London, the art-going public were mortified.

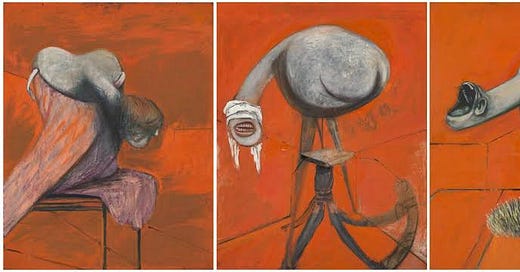

The painter Francis Bacon had exhibited his triptych, Studies for figures at the base of a Crucifixion, produced below, described by his biographer Michael Peppiatt as “three figures, with phallic necks, one with a paw that looks like a scrubbing brush which is snarling, and they are baying their anger, their pain, their distrust of life.” This was not what people wanted to see after the years of war they left behind, but whose proverbial, and in some cases literal, scars endured nonetheless. During the Khmer Rouge, overnight, the entire urban population of Cambodia was emptied, separated, and hounded to farm in the countryside under a harrowing dictatorship that lasted years. I was stunned by what happened next. When the dictatorship lost the war with Vietnam, people moved back to the cities, taking over empty apartments, sometimes finding themselves the neighbours of the very people who gunned their family. To move forward, do we need grace or do we need anger?

At the end of one of the most moving films in the Oscar line-up this year, Quo Vadis, Aida, based on the Srebrenica massacre in Bosnia, the main character, based on the life of a UN translator, chose anger. It wasn’t cathartic. It was ugly, even. But what does one do with grace as a facade?

The Second World War was a disturbing confrontation with the brazen lengths of human depravity, and the snowballing spillage of life that can come from the ego of a few metastasizing into the hatred of many. How we have come to a point in civilization where we can mobilize entire people to end the lives of other people for a few spots of land, on the basis of constructed difference. India is fighting against China as I write this for land on the mountains that isn’t even hospitable. Soldiers, mostly from the low lying areas bleached by year-long summers, are trucked there with propane, food, water, tents, thick-but-not-thick-enough clothes, and guns. If asked we are told that the victory for this land would be symbolic. And so it goes, the wars of symbolism. War movies that by design teeter towards propaganda, placed the bravado of soldiers as a virtue and not as a coping mechanism. It took me years to figure that one out — what can you do when death is so near but see yourself as a hero of your own story? The gun-toting cowboy as a lone ranger was a product of advertising — trying to sell guns to people who bought into the myth of the wild-wild West, after the slump in gun demand post-war. But after the war is waged, and borders and contracts are drawn, how does art respond?

Bacon’s painting, in this context, was too feral. Raymond Mortimer, a critic noted in his review of the exhibition, “[T]hese pictures expressing his sense of the atrocious world into which we have survived seem to me symbols of outrage rather than works of art.”

That outrage is understandable, but to only have outrage?

I am not suggesting that Bacon’s paintings are a response to the war. Critics have noted that the revenge motif in his work was perhaps against his father who rejected his sexuality. It could also have been a celebration of pain, for Bacon loved the act of brutalizing himself — at one point Bacon was in love with a sadist who threw him out of plate-glass windows from the second floor of a house. Many of the critics in the documentary on Bacon’s life, A Brush With Violence, noted how this lover was a “positive influence” on Bacon’s art. An asthmatic painter, gasping his way through the precarious Cold War, Bacon “gambled everything on his next brush stroke”. There was nothing constructive about his paintings, even as they were figurative, for the most part — mangled in ways only Bacon can.

I am instead asking how do we as viewers of art respond to works being produced in a time post-disaster. The point of subjectivity is that we all will never see the same thing for what it is. But what about collective subjectivity? When we all experience the same pain and find excuses to see it rattle out in the same places. Bacon is an interesting subject as an artist, but where we are right now, in India — trying to secure oxygen, plasma, and hospital beds for loved ones, acquaintances, and followers, as the cemeteries and hospitals are full, unwilling, unable to house more dying, dead bodies — I am thinking, rather oddly of how we, as viewers, move forward. I recognize that to even be able to think this, in a time where people’s minds are roving around the immediacy of needs, is a privilege, a distraction, a privilege to be distracted. Here is where we are. But I am unable to take my mind of an artist I met who had a physical sculpture made of blood red thread woven around nails, telling me how it represented the bed of arrows that Bhishma slept on during the war in the Mahabharata. Part of me rolled my eyes. Part of me couldn’t take my eyes off the red dyes.

Languishing

I am invoking George Sander’s idealism towards fiction for a moment, even as I don’t entirely subscribe to it. For the longest time, when people asked me why we should read, my answer would be, “Reading makes you sympathetic to others.” Then as a disciple of Econometrics — correlation isn’t causation — I realized it was all idealized nonsense. Reading can make you sympathetic to others. But was that why I was reading? I still spouted the line nonetheless because it felt true. That as Saunders says, “Fiction [is] a vital moral and ethical tool”, that it helps us how to think, and not what to think exactly. That it doesn’t have to solve problems as much as formulate them in ways that aid meaning-making. It took me years to just pick up a book and when asked about why I read, say, “I feel good when I read.” Which is why I am gravitating towards the kind of writing that isn’t authorial or well-researched as much as charming and persuasive. It is why I have moved away from reading critics who always sound like they have a sore, melancholic stick up their butt. Their breadth of vocabulary and raw material might be stunning but to constantly have a whining background score playing does little for me. Reading, I am growing to understand, is such a primal pleasure. Literary quality aside any time Vaasanthi puts out a biography I burn through it. The last time I refused to eat or shower, reading the entire biography of the politician-writer Karunanidhi over a stinking, sunny Sunday. This Sunday was supposed to be about gouging her biography of the superstar Rajnikanth. But instead I had to submit a 3k work review of an awful book and think through this newsletter, while prepping for a 12 hour work Monday.

The famous New York Times article that is circulating has mainstreamed the word “languishing” — between burnout and depression. One of the suggestions, because there always are suggestions, is a Netflix binge. Another primal gasp; inhaling Looking waiting to see Russel Tovey’s butt, or Sebastian Stan’s full frontal devi-darshan in Monday. Art is actively designed to make you forget you exist in the world you are experiencing it in. Anything that deepens our embedded existence is anathema. Any flight of imagination is not just courted, but deemed medically necessary. Any metaphor to explain the world to those who have lived through it is rubbish-rabble.

Post-Languishing

When writing about Joji, the Malayalam adaptation of Macbeth set in a rubber plantation in Kerala during the COVID-19 pandemic, I had stressed how brilliantly it played its cards. That to tell a story set in a time of devastation, devastation need not be the plot-twist. It gave hope that when this is all over, when we make stories about it, paintings, sculptures, we can have a light touch approach to using it as a background.

The absurdity, the violence, and the lack of any coherent answers or explanations made [the pandemic] ripe for film fodder. But who wants to see a film on the virus having lived through the ongoing lockdown? The worry was an overrepresentation of COVID-19 as the primary conflict in movies. The worry on the other extreme was a kind of escapist cinema that has no space for disease or death.

…

At the very end of the film, when Joji wakes up from his attempted suicide instead of familiar faces, he sees strangers in that white hazmat suit peering at him like fresh meat. It’s deeply funny but also, if you think of it, deeply unsettling — to be so alone, to be untouched, to be unconsolable by the physicality of love and care. It’s the kind of duality that plays off one another — deeply funny, deeply disturbing. To tell a tale in the times of COVID-19, one must be able to embrace both.

There is no doubt that the virus will linger in our storytelling. I find it interesting that even today when we speak of the Progressive Artists of India, those Midnight’s Children who lived through the 50s and 60s, we still see traces of partition trauma in their paintings they completed decades after the split of the subcontinent. When Krishen Khanna, one of the progressives was interviewed he noted, “The partition was a monstrous, terrible thing that happened. When one is afflicted with such a situation, you do not sit down and start painting it. You let it metabolize within you. I am still in the process of painting these paintings.” He said this in 2017. Every time a diagonal line is seen in any of the paintings of these artists, the go-to interpretation is the border that separates India from Pakistan, home from home.

So there is, on one hand an active re-interpreting of post-disaster art as if it had semblances of the disaster. On the other hand, there is an active subversion from anything pre-disaster, almost in the thrall of a new world. To take that moment of distraction we feel when we binge, and make a new world out of it entirely — abstract expressionism, surrealism, the post-modern, the post-structural.

“I mean, I’ve heard it said a lot that postmodernism and abstraction were a response to a Godless world, to the splintering of reality, the breaking down of form. That in the wake of all the atrocities and privation and horrors of war and the suffering of man’s inhumanity to man, nothing seemed important or real or that old hierarchies made no more sense. And I think I always approached that stuff with a very protestant skepticism. It always seemed suspicious to me. Like wearing jeans in church. What do you mean you are just now privy to the sufferings of the human soul? You wore slacks during slavery, but somehow WWII has you embracing the chaos of existence?” — Brandon Taylor

That these two approaches will exist side-by-side is inevitable, given how so much of interpreting art is reactive to the times it comes out of — as either embedded in it, or a reprieve from it. If the artists are canonized it becomes easier for we can afford interpretations on the basis of anecdotes from their lives. It might be off the mark, but who is to tell you that you are wrong? The artist after all lives on, not in their body, but in their legacy.

In 1988, Bacon is in love, inspired again, fueled by that velvet passion, and turns his attention back to the feral paintings of 1945, and reworks them, scrubbing them clean of blood-clot. As Mark Stevens notes “It was not brutish any longer. It’s as if the monsters had been turned into silk.”

You know the part where you wrote about how you used to reply when someone asked you why you read, your answer would be, “Reading makes you sympathetic to others.” But now, thankfully, you say, “I feel good when I read.” The transition has been almost cathartic, for both you and me, but it also makes me wonder that we were made or conditioned to say better than that. It was supposed be like a "well-written" review like that of a critic in order to 'justify' your reading. Like it was supposed to be an academic or intellect activity and not just a pleasurable activity. When it could have been as simple as saying - “I feel good when I read.”