On Nomadland

The film, and the journalistic account it is based on, asks "What's a home?" and then quickly, "What's in a home, anyway?"

You don’t need to have watched the film to read this. It’s not about the film as much as what the film by Chloé Zhao, and the book it is based on by Jessica Bruder says about the world we are living in and heading towards. Do subscribe for the weekly essays to parachute into your inbox. Last week I had written about what India is watching, and while the obvious answer, as pointed out by a reader was “IPL Cricket”, there is more to it — K-dramas, casteist rap videos, dubbed Telugu films.

“My beautiful America, vast in its brutality, and brutal in its vastness.” — James Wright, Heraclitus

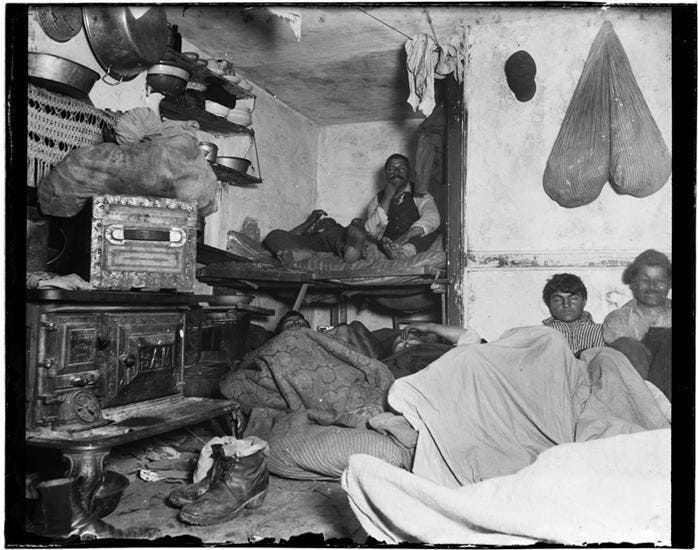

In the beginning we were nomads, the first flush of homo sapiens germinating in Africa about 100,000 years ago, and moving, nudging along shores, across inlands. Some reached Australia, some India, some stayed, some roamed and circled back. Over time, we put tents to the ground, and then later, bricks, solidifying our relationship to the land. Ownership, private property, capitalism, colonialism, the 21st Century, and somehow, some of us find ourselves circling back to the very beginning — to being nomads. The impetus for being peripatetic this time is not “lack”1 of knowledge, “lack” of innovation, but perhaps the too-much-ness of it. The too-much-ness of knowledge and innovation that has made stable existence unaffordable and insufferable.

The And-ness Of Nomadland

Chloé Zhao’s movie, Nomadland, the toast of tinsel town, winning awards at the Venice Film Festival, Toronto International Film Festival, Golden Globes, BAFTA, and a bevy of Oscar nominations, follows Fern (Frances McDormand) — displaced, widowed, and broke. When her factory town, Empire, ceases to exist after the fulcral factory sputters, then shutters, she takes her white van, christened Van-guard, and roams the country. In December 2011 the factory shut down. By June the following year, the town had to be hollowed out.

It’s a lonely existence (the loneliness suggested, and not evoked by the piano in the background), where she makes money by working at the Amazon Fulfilment Centers and National Parks that dot the landscape, hiring nomads for seasonal employment. One government, one private enterprise capitalizing on the availability of seasonal labour that is earnest and trustworthy. The nomads mostly consist of the Eisenhower generation, the baby-boomers, who lived through the promise and demise of the American industry; what was supposed to give “workers a sure footing in the middle class and a chance to raise a family without fear of displacement” had given way to flat wages and rising rents, an economic paradox where staying alive, staying sheltered was subject to the whims of an economy.

The movie is based on Jessica Bruder’s journalistic account. Bruder first wrote for the Harper’s in 2014 about this nomadic sub-culture moving “like blood-cells through the veins of the country” and later a book. She lived in tents, and bought a van for herself, christened Van Halen after the rock band, following the nomads, getting stuck, getting lost — an immersive account padded by journalistic rigour. (She had to submit shower bills, from showers in laundromats while traveling, to Harper’s for reimbursement.)

When I watched the movie, I was struck by Zhao’s capacity to not give in and provide comforting answers — is the nomadic life a reaction to the brick-and-mortar life being unaffordable or to it being insufferable? She chooses and — unaffordable and insufferable, and this and-ness is a reflection of Bruder’s work which also refuses to make the nomadic life sound wretched or edenic. Zhao also uses the real nomads that Bruder interviewed in her work, playing themselves, a ploy Zhao used even in her previous film The Rider, where the injured cowboy played a fictionalized version of himself.

Part of this and-ness is accomplished in the film by not showing us how Fern lived before Empire’s shutter. The film begins after the shutter, when Fern, smelling the jacket of her dead husband, is now revving up for a life on the road. (Anthony Lane begins his New Yorker review with, “One of the things we learn from the films of Chloé Zhao is this: bad luck is the stuff that happens before a story begins.”)

We don’t get a searing sense of what she has left behind, except in sputters of conversation, and so we don’t get to yearn for it for her. But not to make the road a tar-carpet of wanderlust, Zhao, at the very outset, shows Fern doing two things — peeing out in the open and singing to herself, one biological necessity, one recreational urge to make the breathable life bearable. You can think of n-different ways to show a character on the road, but the fact that Zhao shows only these two specific acts in the very beginning, shows how she will treat the idea of being a nomad — with realism, with charm, without shying away from what is dreary, and what is dirty.

This also lends to the sense that being on the road, while precipitated by economic distress, isn’t distressing entirely. There is a community of nomads who collect and exchange joy. The road becomes a way of life, and the sedentary world seems like a distant dream.

“So what began as a last ditch effort has become a battle cry for something greater — being human means yearning for more than just subsistence. As much as food or shelter we require hope. And there is hope on the road.” — Bruder

For Zhao being a nomad is a way of life that eludes simple explanation. On some days it is lonely. On other days it is lively. The triumph of the film, and Zhao’s method of cinema — planting her characters in that fertile field between fact and fiction — is in aligning itself so interchangeably with reality that like real life she doesn’t seek ready answers, but convoluted questions, circling inward and outward, designed to not be answered.

A.O.Scott in his New York Times review noted how the film was weakest when it tried to be a “film” — by introducing a character whom you know the very moment you lay eyes on him, that there will be a saviour angle involved. Otherwise not much by way of a “film” takes place. The closest to escalation we see in the film is vis-a-vis Shakespeare, where in the beginning Fern quotes Macbeth, stuck in that moral-immoral dilemma, and in the end she quotes a Shakespearean sonnet, a poem whose language defies binaries, defies even language.

At the end of the film, and this is a “spoiler”, Fern decides that instead of the readily available option of settling down that is offered to her, she goes back on the road. This decision distressed my friend who thought she “could have been happy but she was too prideful”, that “she broke the best pattern she has, of saying no to help and then accepting it”.

I disagreed because I thought it lent to Zhao and Bruder’s conviction that once displaced, stationary life doesn’t seem like a solution as much as a condition to endure. I also disagreed because perhaps Fern might come back, on her own terms to be with this man. She always hated being told what to do. Why would she relent this time?

The Demography

Bruder noted that when she showed photos of her research to a black photographer, the lack of any black nomad was pointed out to her. Even in the film, I only saw one black person. I don’t think I saw any Asian wanderer. Bruder takes a small aside discussing how to even live in a van, the depths of economic disenfranchisement, is a racial privilege that involves a constant tussle with law enforcement. That fear of three knocks on the door, parking with the front facing the exit so you can make an easy run, having white vans which are more inconspicuous, these are insurances that perhaps won’t be enough to protect a black person from arrest or worse, death.

The demography of those traveling is also stilted age-wise. When we see the few young people travel, called “crosspunks”, “dirty kids”, or “rainbows”, it’s mostly an instinct to see beyond the horizon. Bruder interviews a young trans man, who gets his refills of testosterone by post. When the old people, who make up most of the nomads travel, it’s mostly knowing that the horizon is actually a dead-end, galvanizing community around trauma. Theirs is a story of the fraying ends of the social contract, of the failure of capitalism, of democracy, (Democracy requires voting which requires a stable, rooted existence to vote) of demography (Nomads are often called “the demographer’s nightmare”).

When we see young people on the road, they are seated criss-cross-apple-sauce smoking weed, swilling beer, playing the guitar, dreadlocks. The older ones stare at the horizon on lawn chairs, sipping black coffee.

“I am glad I shall never be young without wild country to be young in. Of what avail are forty freedoms without a blank spot on the map” — Aldo Leopold

An example many of the older nomads in Bruder’s book give is of those wandering during the Dust Bowl. Unlike those refugees who hoped for a return to the status quo, a stationary being, nomadic living isn’t a temporary solution till the bad times tide over. It’s all there is now. Of course it is a struggle — the back-breaking, sometimes literally, work at Amazon, beet farms, and National Parks isn’t easy. Bruder herself tried to go undercover, working in these places, leaving within a few days with aches in muscles she hadn’t consciously thought about for years. These are people over the age of 60.

This brings up the uneasy question of death. Being so close, so prone to it, how does life on the road fare, where a burst tyre in the middle of nowhere is not an exception as much as an inevitability? These are not people overly optimistic about the future, one of them noting that perhaps when the end feels near he will wander off into the wilderness, and take his life with a bullet. It’s that constant tussle of “bringing life into focus by compressing it into a small space”, and then wondering what remains of this life to give, anyway.

Back To Where We Began

The beating heart, more subtle in the movie, more fact-fuelled in the book, is the demise of the middle-class, and not due to a lift in circumstances out of it but a slow, steady plummet. The 2008 crisis saw a sudden spike in those willing to pack their life into a room with wheels, zooming off into an uncertainty that seemed more promising than the certain disaster sedentary life was turning out to be. The steady rise of policies that frame income inequality as the logical extreme of meritocracy is furthering the chasm. It took a pandemic to unravel our ideas of market failure as not exceptions but the norm. A journalist live tweeted their slowly falling oxygen level, begging for help, till they stopped. Healthcare is still considered a privilege. The nomads drive to Mexico to get their teeth worked on. Bad teeth, in fact is a signifier of a nomad and Bruder explains that no one grins toothily for photos due to this shame.

Due to the COVID-19 pandemic, last year 54 million people slipped out of the middle-class, globally. India accounted for the majority of this — 32 million people were re-classified as “poor”. The poor of the cities were, on the other hand, hoarded away in trains packed like canned sardines back to the villages. The market, on whose invisible hand we staked out existence, had failed to materialize. Much like the uptick in van sales was an outcome of the recession, I wonder how this sudden relabelling of economic categories will manifest.

Then there is the impending climate emergency, where entire islands are being evacuated. In the midst of the pandemic, last year cyclone warnings led to huddles in government facilities where social distancing was at best, an abstract idea. The climate-fiction Booker Prize shortlist last year, The Last Wilderness by Diane Cook follows a post-environmental crisis world where hoards travel together on foot. The book was also dystopian so there was a government that mandated movement, sending guards to enforce migration if the they stayed at one place for too long. Many of the nomads, advocates of minimalism and enviromental sustainability (there were vegan meals served when the nomads congregated) see their lives as both by-products of and solutions to the upcoming catastrophes. We have to confront the idea that rootedness might be a social construct and not the inevitable end of evolution, and that the growing individualism that began with property rights will have to contend with a world where crises have a wholesale quality of devastation.

When I was in school, during a stay-back evening session of Debating Society, we were talking about homes. One of the seniors, a man I admired and in whose accent I tried to find mine, said, “A house is made of bricks. A home is made of love.” I loved that artificial abstract distinction and made a sincere note to discuss it with mom and dad over dinner. Over time it was a distinction that made its mark across family whatsapp groups as “inspirational quotes” and the difference lost that initial sheen, giving way to irony. However, it was a distinction I came back to while watching Nomadland, where if you can differentiate house from home, you can also differentiate houseless from homeless. But this time it's not abstract or artificial. It's a self-preservation instinct. When asked by one of her former students, “My mom says that you’re homeless, is that true?” Fern, flummoxed but certain, replies, “I’m just houseless. Not the same thing, right?”

I am putting lack in double-quotes because the idea that nomadic living, specifically vis-a-vis tribes, was often seen as primitive, as unbecoming of a modern civilization by the early anthropologists.

Though i have watched the film and loved it a lot. After reading your essay, I'm more than compelled to read the original Journalistic account by Bruder.(at least, the Journalism student in me gotta read this)

thank you prathyush