On Malik's Nihilism

Malik, like Nayakan, produces a virtuous gangster, whose very pursuit of "justice" muddies its very meaning

Last week I wrote about the bubbling, burgeoning genre of teen-dramas. Like all my posts, you might have sensed an element of doubt in my writing, in being unable to give concise conclusions and instead hovering over an idea poking holes both ways. I would like to point you towards Amartya Sen writing about doubt, citing a 17th Century Francis Bacon text that sees doubt as both guarding us “against errors”, and doubt that initiates us further into inquiry, “enriching our investigations”. Perhaps my doubt is more of the former, because I realize how easy it is, to come to conclusions on the basis of just feeling, and how wrong such conclusions can often be. Either ways, I reviewed another teen-drama this week, the second season of the lovely, kind, and odd Never Have I Ever.

This week, I want to talk about the nihilism of being a virtuous gangster. When I use the word nihilism, I mean the belief that all the values we think are the bedrock of society, like “justice” and “truth”, are baseless and that nothing can be known, and thus truly communicated. I am not talking about the implication of nihilism — which can be extreme pessimism and perhaps even existentialism, where life makes no sense. But just the nihilistic aspect of society, and more specifically, of the state, in films like Nayakan and the recent Malik. As always, if you agree or disagree, write to me.

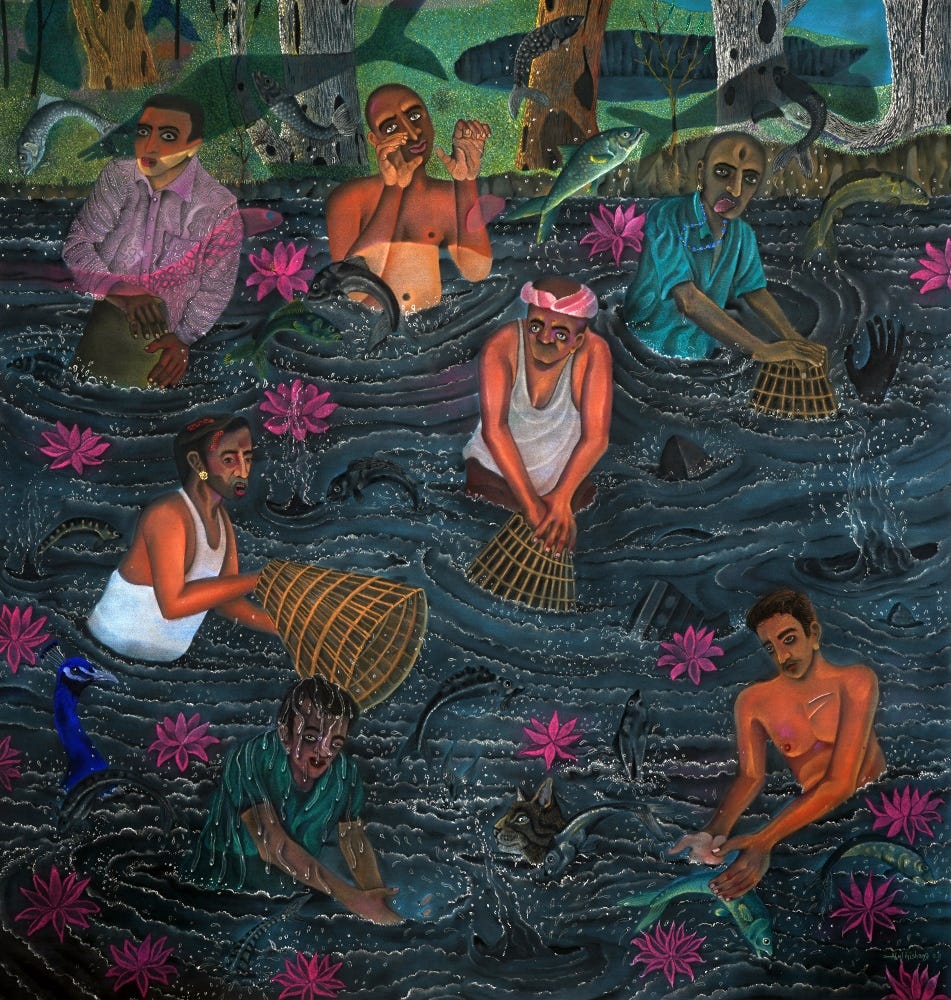

There is a scene in Mani Ratnam’s Nayakan (1987), where Velu, the Tamil don prising over Dharavi in then-Bombay, is trying to placate his grown-up daughter, standing incensed in front of him, accusing him of brutality and playing god.

The previous day, a police officer of all people, came to Velu to ask him for justice. The officer’s daughter had been raped on her way home (though the word ‘rape’ isn’t used I think, the father speaks of the act in vague verbs insinuating it) by men who were connected with powerful political families. Since the police, shackled and supported by such connections, could do nothing about this, he asks Velu to help him seek out “justice”. Velu’s men attack one of the rapists, squeezing his hand between the door and the body of his car, and Velu’s daughter sees this “miruguthanam”, this animal-like brutishness.

She realizes that her father, for all his loving candour and lively jibes, is a goon, and confronts him about this in their veranda with a Tulsi plant centering a galaxy of kolams and white, clipped, cooing pigeons. Velu in his calm-cool baritone argues that the violence needed to happen because “he gave his word” to the officer, but Velu never tells her why exactly the violence needed to happen. When one of his henchman ventures to explain that the boy in question is a rapist, Velu stops him before he utters another word. That he doesn’t want her to know why he is doing what he is doing, is a curious decision, narratively speaking.

Velu is clear that he wants both his son and daughter to stay away from this business of playing god, this don-dom that gives him as much brutality as bird-song. When his wife is killed in a shoot-out, he parcels both his kids to Chennai, away from his empire, where they are raised. Later, when his grown-up son keeps trying to help him, Velu keeps pushing him away. Velu recognizes that to be a don is to live your life with a kind of casual existentialism — will I or won’t I live by the end of the day? He knows that what he is doing — murder — might be bad. But he also knows that why he is doing what he is doing — to protect people — is good. He knows the goodness in most minds cancels the badness, and produces a rationale for being a don, a protector. He understands the allure of that logic, the logic of revenge, which some might say is the logic of justice, which is why he doesn’t even let his daughter negotiate it, making sure she doesn’t know that the man she is arguing for is a rapist.

This is why while his daughter keeps arguing in support of the man attacked and the systems at place for justice — the police, the courts — Velu doesn’t contradict her, arguing their compromised condition. Instead he explains how as a child on the streets he learned to deal a blow with a blow-back. The film, sympathetic to him, plays the syrupy lullaby in the background as he explains the circumstances he grew up in. In the end he says, he did what he did because that is what he thought was right.

This scene is a fascinating study about the inadequacy of language in films. A lot of times, while watching a movie I am a bit struck and lost by why certain characters are doing what they are doing. I have always seen language as that instrument through which we can move closer to the problem we are trying to articulate and then reconcile. But scenes like this tear that theory in half, because suddenly you are confronted by the impossibility of language to express the complication of answering, “Is it okay to murder?” with “Depends on who is being murdered”.

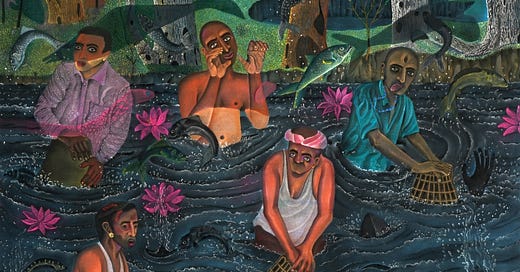

Malik, the Malayalam gangster drama that just premiered on Amazon Prime Video, follows in the nihilistic genre footsteps of Nayakan. Fahadh Faasil plays Ali, who is another gangster-of-circumstance like Velu, by which I mean it isn’t the allure of violence that got them to it but pressing circumstances — in Malik it was poverty and the murder of children at Ali’s godown, and in Nayakan it is how Velu’s father, and later foster father are murdered by the police. Violence is seen as not a provocation but a reaction to a provocation. In both cases it is the state — Mumbai Police or Kerala Police — who are the provocateurs. Both films, unsurprisingly, are based on real life events — Nayakan on the Tamil don Varadarajan Mudaliar, and Malik on the Muslim-Christian tensions concocted by the police in Beemapally

Are Velu and Ali heroes?

It is a little complicated because it requires us to unpack inherited notions of goodness and badness, heroes and villains. As a child, individual acts of violence were considered bad, punishable, kneel in the corner, write “I am sorry” 1000 times. The underlying notion is that what you think you are achieving with violence, you can achieve without it. The cracks in this argument can be seen early on, because the popular kid, the strong one whom no one would mess with, was most probably not the same as the Head Boy or Head Girl who are climbing a different kind of ladder, one that rewards brain over brawn. Suddenly, what we initially considered moral clarity is now seen as a trade-off.

But then we grow up, the ifs and buts accumulate in frequency and intensity. What if the you are violent out of self-protection? (I remember a court scene in a corny Hindi film, I don’t remember which, where a judge says that violence under no circumstance is acceptable to which the accused gives the judge a box to open. When the judge opens it, he crab or a scorpion or a snake emerges — I don’t remember which — and the judge, afraid for her life, uses her gavel to smash the animal dead. The accused smirks asking whether her violence in self-protection wasn’t necessary?) What if you are violent because no one seems to notice how you are being violated constantly? What if it is not individual acts of violence but accumulated, systemic acts of violence of which an individual is a mere instrument? What about the bubbling hormones, the gift of evolution, in that moment of humiliation where you just want to push back?

The criminal justice system was proposed as a solution to a lot of these questions, but as we grow older we realize the rottenness— Is the criminal justice system meant to punish or reform the aggressor? What if the very thing you are staking your ideas of justice on is the very thing that kills it?

We are often told of an ideal, inter-mixed society as the utopia we work towards, with a tame legal hand over us. But what if no one wants to work towards this world? The Pew Research Center’s Study on Religion in India, based on 30,000 face-to-face interviews of adults conducted in 17 languages, concluded that “Indian religious communities live together, separately.” That while on the one hand there is a “commitment to tolerance”, there is also a “desire for religious segregation”, the latter is about not wanting inter-marriage, mixed friend circles, and neighborhoods. The last of the three — neighborhood — is very tricky. Author Ghazala Wahab in an interview had spoke about how, growing up in a Muslim ghetto, the idea of progress was the idea of getting out of there, but then when Hindu-Muslim riots struck, and when her family realized that no one would protect them in their richer neighbourhoods, the preference for safety got them back to the ghetto. That after a while, in a society so viscerally segregated, to live together is not just sharing similar economic qualities but also similar faiths, similar castes, similar languages. This brings up a very interesting possibility that Pew notes — that segregation might not be seen by many as discrimination, but a necessary insurance. Thus, their ideas of justice, and fairness too is an insurance against this inherited notion of courts and the police. To go to the police to file a complaint when you are wrong is an act of progress, or privilege, and might backfire, to which one must retreat into one’s own cultural juggernauts — the don.

I always feel that knowledge can complicate and muddy, as opposed to simplify things, and thus to know more is not necessarily to have more clarity. Knowledge is often associated with guilt, and I guess violence and justice are one of those things.

Which is why what Mani Ratnam does at the end of Nayakan is nothing but a stroke of dizzying brilliance. He has Velu’s grandson, a young boy, ask him in the penultimate scene before he is tried in court, “Neenga nallavara kettavara?" (Are you a good or a bad person?).

Velu thinks for a bit and replies that he doesn’t know, a willful internalized greyness that exists side-by-side with his god-complex. The “greyness” is the incompatibility between what he is doing — committing acts of violence — and why he is doing it — to protect and serve his underserved community.

Malik has the same fraught calculations. When both Velu and Ali commit their first murder, the camera is on their face, and the aggression, which should belong to a villain, suddenly bubbles to the surface. They have the instincts of a feral beast, but the intentions of a leader. “Grey” might be too tart a word to describe them, perhaps, because at no point do our affections for them stray. They might even be as Robert Warshow suggested of the American gangster movies’ portrayal of burly men of the late forties, “what we want to be and what we are afraid we may become,” as opposed to the pathetic, rotting remnants in Godfather.

Malik however doesn’t have the space for this kind of rumination the way Nayakan had. It’s so dense that one often feels less like an audience but a reluctant tourist to a rambling guide. I had to watch the opening 12-minute one-take stretch twice to register all the characters, what each character is saying, how each character is related to each other, and what each’s intentions, hang-ups, points of tension are. So busy we are trying to follow the dynamics, the subtitles, we don’t even have the space to look at the wall-hangings, or where they keep their phone chargers. It’s the kind of film where we are able to, sometimes barely able to, grasp only what’s immediate and in front. The nihilism is thus not the first thing that registers but its shadow is apparent throughout – when Ali talks of the ungodly acts he has performed and thus wants penance for, but then blames his wife for making him renounce the life of a gangster because people are suffering without his strong hand. I just hoped the film would not hurtle on so impatiently.

I don’t like feeling stupid or lost, I don’t think anyone likes feeling stupid or lost, and when films do it so egregiously, you almost want to do the cinematic equivalent of hurling a book across the room. I feel like a gatekeeper when I say things like “Stick with the film though, because it is intensely rewarding”, but I’ll do exactly that because the film is so full-bodied and has such a moving end that its density can be over-looked if not forgiven.

But Malik makes a very interesting distinction which Nayakan doesn’t. That to be this leader, this don, it isn’t enough to just be able to stand up and aggregate their despairs into one howl. It is also important to stand by them when the despair becomes demanding. Ali tells the girl he is trying to woo, that mobilizing is only the first part of truly being able to bring change. You must stick by then, with them.

While Malik makes the violence seem more violent, with Faasil’s eyes flaring in blood-lust, in Nayakan Velu is filled with an immediate rush of guilt. Because Nayakan, unlike Malik, is not just about an accumulation of events, it has to provide narrative and philosophical pushbacks against the gangster figure. So, when Velu realizes that the policeman he killed has a mentally challenged son, he decides to pay the family a monthly amount as part of his “debt”, and later on even hires the son as his personal bodyguard. In Malik this guilt can be heard in Ali's howls as he tries to prevent another loss of life within the family.

Now, hereon there are spoilers.

It isn’t a coincidence that in both Nayakan and Malik, the don that holds power and thus promise in the eyes of the downtrodden, dies. Both these characters are creations of the state’s provocation. The state can never be reformed, and so the virtuous gangster will always exist. The only way to stop asking the question of whether they are heroes or villains, is if they cease to exist, rendering the question moot. What this also does is create an elegiac impression of them — when you mourn someone their faults blur, their virtues bloom, and their life becomes a gilded tomb. It is easier to feel like they are heroes of the story, even if we don’t want to get in the weeds of what this heroism comes at the cost of.

But in both films there is a filament of hope, because towards the end it is a policeman that comes to them, telling them that they finally understand why people love Velu, why people love Ali so much. Understandably, it is the least effective moment in both films because this policeman figure is thrust in as an exception, more so in Nayakan where suddenly the policeman realizes the folly of the wheels, that he is a cog of. Such sudden swerves of sentiment is always suspect.

There is, thus, in a sense a “completeness” to both stories, by which I mean no further intervention would be necessary. Both Velu and Ali were responsible for violence, and it is the children of those who were violated by the goons who ultimately do the killing. There is no scope for further intervention. The cycle of violence feels neatly shut without scope for spiraling. Or at least that’s how it feels like as the credits roll.