On Muhammad Ali's Shadow In Toofaan and Sarpatta Parambarai

Two films about boxing released with a week, both attempting to differentiate violence from craft — boxing as thuggery, from boxing as sport

Last week I wrote about Malik, the Malayalam ‘Godfather’, whose Malayalam-ness took a genre template, wedded it to rooted, real events, thrust you into it in-medias-res, tested your patience to only reward it that much more. I used Nayakan, the Tamil ‘Godfather’ film of the late 80s to speak of the genre’s nihilistic tendencies and pursuit of warped justice.

I also want to return to a piece I wrote in the beginning of the year, where I decided to abandon reading goals in the hope that I am able to resurrect that feeling of joy while reading. Some updates on that — I started becoming more comfortable leaving books mid-way to circle back or not circle back to them eventually; I started expressly reading books I love, thin-ness and thick-ness isn’t a factor in my head; Then, I played myself by beginning to review books on the side because I thought ‘Hey, I read anyways. Might as well do it for money.’ The books I am reviewing are mostly duds, and the money is not much at all. But the point stands, I am happy to detach the number game explicitly from reading, even though numbers will always be there — page numbers and days of the week reminding you how much more of the book is left. I suppose some tendencies can’t entirely be excised.

This week I watched two boxing films — which if you asked me a year ago would be two too many — but I was surprised by how effectively they made me forget that boxing is violent, immersing me instead, at least for a moment, in its poetry. Both films nod heavily to Muhammad Ali, and so I weave him into my impressions of the films.

As always, write to me your agreements or disagreements. If you like what you read, share it with someone who might also feel the same way. Subscribe so my e-mail list feels bulkier.

In 1814, Norway slipped from being a dependency of Denmark, to one of Sweden. Sweden allowed Norway autonomy in internal affairs, for which Norway created its own constitution the same year, the constitution of 1814. Over the course of the 19th Century, however, there would be movements to establish Norway as a nation in its own right, and in 1905 Norway became an independent nation state.

With this movement, people mobilized around the idea of a Norwegian identity — Norwegian language, Norwegian music, Norwegian art, Norwegian architecture, as not just separate but distinct from Sweden and Denmark. This also included publication of Nordic myths and folk tales. Norwegian pride, associated with borders, a distinction from their neighbors, came out of this project.

Abstract away from this example, and you’ll realize that so much of the differences that exist today were first constructed arbitrarily, like borders, and then edified over centuries, sometimes millennia into solid categories with the help of myths and mores. Today, we cannot imagine our worlds without some of these categories — like gender, sexuality, religion, nationality. Culture is thus that loose thread we hold onto to assert this difference. Pride is the grip of that hold.

To then be told, by your wife of all people, to remove pride and honour from your mind as you mentally prepare for a boxing match the following day, where you are representing and thus resurrecting your community’s name, is so farcical, I was surprised that I was even moved by this dialogue in the first place. (The subtitle: “Why do you associate the clan with pride?” But what else do you associate it with?)

The film, Sarpatta Parambarai, places Kabilan (Arya) as this fulcral figure around whom representation and resurrection rests. He is from the Sarpatta clan, and is fighting against the Idiyappa clan — the difference between the two is a minor skirmish that over time magnified into animosity that was first constructed, and then inherited, till it became an indispensable identity marker. As a viewer, you don’t have to be convinced about why there is this animosity, but you have to be convinced that there is a breathing acid that divides the two. I was. So, even the brief asides of explanation — dull, unconvincing, contrived — make no dent on the viewing experience, which is, to put it lightly, glorious.

The director, Pa Ranjith, has made movies in the past that I am wary of. His previous two attempts at melting his Ambedkarite ideals and imagery with the mainstream munch was, to put it lightly, intolerable. Kabali is a film I regretted not walking out of the theater because it kept getting increasingly dull and bizarre. But with Sarpatta Parambarai he does something so splendid — reworking an iron-caste genre — my ears thrummed for hours after with the joys of it.

For one, the “winning” match that we expect to be the climax is actually at the interval, and we are left wondering what would happen next, giving us a second half that is more intimate, devoid of the larger politics of the time. For another, he doesn’t shy away from discussing the very morality of boxing as a sport in a context where boxing isn’t a slippery slope towards indiscriminate violence as much as a logical stepping stone. All this, while retaining the anti-caste imagery of Buddha, Blues, and Bhimrao Ambedkar himself, even as caste itself isn’t brought up, replaced by another, equally bizarre, equally arbitrary division — that of “clans”. The word used for “clan”, parambarai, can also be used to mean tradition, a cultural inheritance. So we see how tradition, culture, blood lines create and accentuate an artificial division that over generations becomes but natural. Take this film three generations down and I wonder if the economic fortunes of the Sarpattas and the Idiyappas diverge. Take it three more generations down and I wonder if research will be done comparing the IQs of the two clans, reporting a statistically significant difference. (Hard, tired nod to relatives who keep telling me about a research project from Israel which has compared the Brahmin brain to Israeli intelligence, asserting their thayir-sadam superiority.)

Kabilan is established initially entirely in terms of his reverence to his coach, the vathiyar, who is a member of the DMK political party. Through him the politics of the time — mid 70s, Indira Gandhi’s emergency, and her anxiety about Tamil Nadu asserting its statehood under her iron grip, dissolving its parliament — comes into the movie. So, when the coach gets arrested and disappears from the narrative, any semblance of the larger politics is slurped off, giving the second half of the movie time, instead, to delve into the intimate lives of Kabilan and his family. We finally see who he is and can be once that veneer of reverence and the distraction of larger politics is scratched through. It’s a screenplay hack — to introduce a character so incredibly aligned to goodness, so that in the second half, you can slowly let him simmer in villainy as the one thing that anchors his goodness is taken away.

But even as Kabilan’s villainy surfaces, it never over-powers. For example, right after he commits the worst things you think he could do, including calling his only child then, a daughter as his son, the film suddenly injects a flashback to Kabilan’s childhood where he sees his own father, also a boxer who gave into thughood, hacked in front of his eyes. Ranjith, the co-writer and director, so masterfully plays with us — giving us a reason to hate him, and right after, giving us a reason to reconcile this hate with our affection and care for him. It’s like pinching you to ask, “Do you still care about Kabilan?” Of course we do.

This brings me to the larger semantic question around boxing and violence itself. The boxing genre and the godfather genre have one big distinction. While the latter glorifies violence, even rationalizes it, the former qualifies it, making a big song-and-dance about how it is different, even diametrically so, from street violence.

But is it?

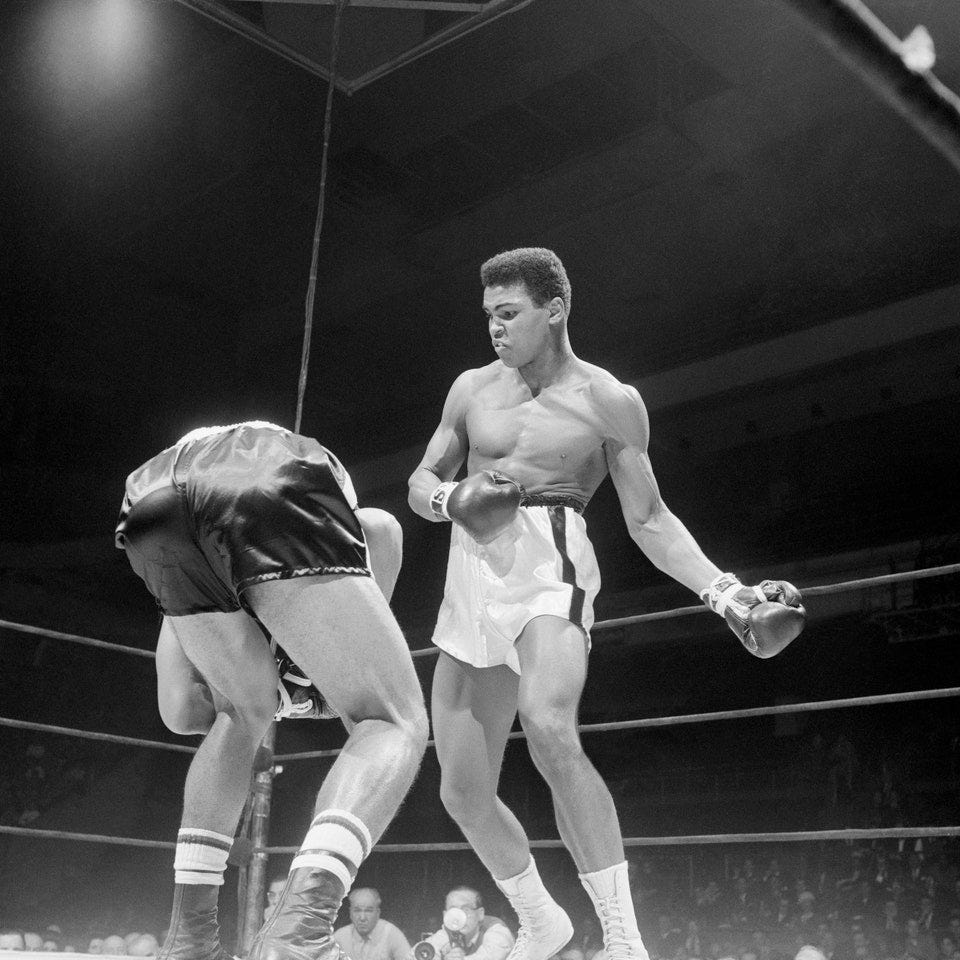

Muhammad Ali’s Shadow

Muhammad Ali died in 2016 at the age of 74. For a man who embodied the physical and the verbal assault on American imperialist pride (Vietnam, Civil Rights, Nation of Islam), it was a hurtful irony that Parkinson’s chipped away at his mobility — both physical and verbal.

His mother had said about his as a child, “I don’t see how anybody could talk so fast, just like lightning.” In the boxing ring, he was more discerning, even if more stinging. When writer A. J .Liebling — who used to write about food and wrestling for post-war New Yorker — watched Cassius Clay (he had not yet changed his name to Muhammad Ali) in Rome, he described the Clays’s performance as “attractive but not probative”. Liebling was confounded by his style many considered “unmanly” — he will dance around, circle, and tire the opponent instead of packing a punch in the center of the ring. Suddenly boxing became more than just the calculated jabs, an artform was at boil with Clay. Besides, there was an amateurish quality that animated his force, full of feeling and hunger, but with accompanying fear that it is a flash in the pan. The “unearned natural ability” that stings and retreats with its own logic, overpowering “honest effort and sterling character backed by solid instruction”.

An unstudied brilliance is necessary to boxing as it is to any art form— and the films that milk boxing into a genre are aware of this, weaving the first realization of this “gift” as a dramatic plot point.

While describing the fight between Clay and Sonny Banks, Liebling dubbed it as a match between “Poet and Pedagogue”. Clay was the former, and there is a literal aspect to it — that he was so moved by a boxing match he saw once, that he conjured up a poem, polishing it in his head. But Liebling through the piece was hinting at something — a poetic instinct for fire, a nimble litheness that tires the opponent with its hawk-eyed relentlessness. The kind of physical poetry that comes from someone who learned boxing at the tender, tempestuous age of 12, to court revenge for a stolen bike. Banks on the other hand had a studied polish under a perceptive, precise coach, but the “one disadvantage of having had a respected teacher is that whenever the pupil gets in a jam he tries to remember what the professor told him, and there just isn’t time.” Hence, poetry won.

Ali’s craft and his myth both became inseparable, and it is this combined quality, snowballed by the elegiac insistence of time, that makes him worthy of dedication — Pa Ranjith dedicated Sarpatta Parambarai to Ali, and Rakeysh Omprakash Mehra’s formulaic yet fundamental Toofaan used Ali’s fighting footage to inspire its main protagonist Aziz Ali (Farhan Akhtar) into crafted clobbers. It’s almost as if the two fighting movies, released within the same week, divvied up Ali’s legacy into his craft and his politics, taking one half each. In Toofaan , in fact, the final fight even has running commentary comparing Aziz Ali's tiring of his opponent to that of Muhammad Ali. Ranjith too noted in interviews how Kabilan's fighting style used Muhammad Ali as a reference. His stamp is there, and not just as lip service to a giant. But as a figure who while celebrated for boxing was also wary of its optics. He had noted how often fighting a black man in a ring surrounded by white men had a jarring racial resonance he couldn't shake off.

But what about the sport itself — a violent ballet that can, often, result in brain damage, disability, or death. There is even a Wikipedia entry for “List of deaths due to injuries sustained in boxing” that requires a considerable scroll. It is not to say that other sportsmen haven’t died performing their athleticism, but there is something so explicit about boxing — the goal is to knockout the opponent by punching them till they physically cannot get up — that is easy to wonder the lethal ethics of the sport. (When Aziz Ali has to explain to his 5 year old daughter why he boxes, he just says, that it is because of boxing that he met her mother, his wife. Simplistic? Perhaps, but how else to explain to a child the ifs and buts of violence? As an aside, I love it when filmmakers attempt to complicate the morals of their heroes by bringing in these children to ask basic questions of good and bad, the most famous being the one at the end in Nayakan.)

It is also why both the films compensate in trying to reframe boxing as distinct from roadside thuggery. In Sarpatta Parambarai, boxing is called a penance, nidhanam. The first time Farhan Akhtar boxes with gloves on in Toofaan, he is incensed when he is punched, taking it as a personal attack. It is understandable, this conflation. When you’re hit, the feelings of humiliation, fear, pushback, revenge all bubble in the brains, and it is hard to train the immediacy of the hormones with the logic of sportsmanship— this is a craft based violence, so don’t take it personally VS this is vile violence, please attack. But he is schooled nonetheless because the man he fights against has no rancour about the bruise; he moves on, and Akhtar’s character is told that this is the grace required in boxing. Akhtar’s first cutting-to-size happens when he realizes that being an effective gunda is not the same as being an effective boxer, the latter requiring a semblance of craft. When his coach first allows him to enter the boxing ring after training he notes that this is his “home”. Grace. Craft. Respect. (Even so, both films fall into that trap where they make the hero’s opponent not a boxing opponent but a villain, someone you want the hero to cut to size. It's where the dramatic pay-off is, and where all ideas of graceful violence goes to die a shrill death.)

They labour the subversive brilliance of this point — that boxing is more than anything else, taking a brutal act and imbuing it instead with the above three words. To be a licensed boxer in Mumbai, you thus have to take an oath to never use this violence for incorrect purposes. It’s also why the redemptive arc for the lost sportsman cannot be relegated by becoming a coach — the way Ben Affleck did in The Way Back with basketball, or Shah Rukh Khan did in Chak De! India with hockey. To resurrect yourself as a boxer is to box, because it is not just about your relationship to the sport, but your relationship to violence, which both men had to deal with. And perhaps this also connects to another point, something more primal, something neither film really discusses because it cracks at the hallowed tradition of guru-shishya — jealousy.

“I could see that McWhorter (Sonny Banks’ coach) was a good teacher—such men often are. They are never former champions or notable boxers. The old star is impatient with beginners. He secretly hopes that they won’t be as good as he was, and this is a self-defeating quirk in an instructor. The man with the little gym [on the other hand] wants to prove himself vicariously.” — A. J. Liebling